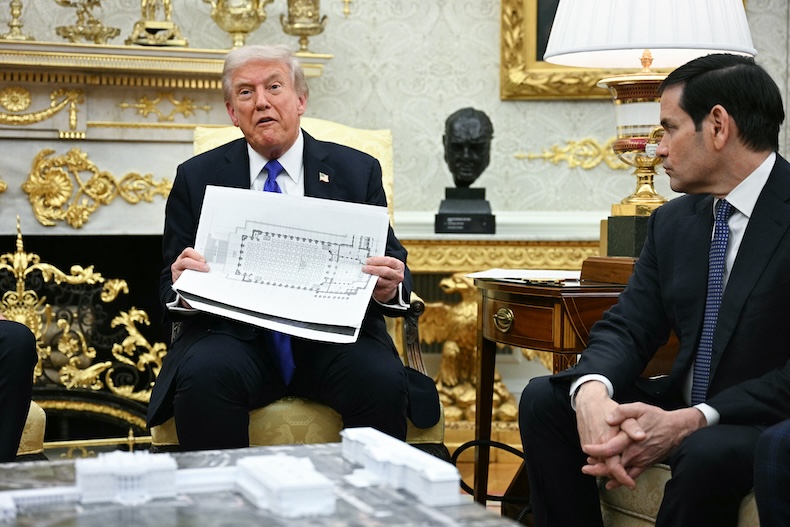

The sudden demolition of the East Wing of the White House last week was an architectural bombshell that has provoked tens of thousands of words of reaction, some of it outraged to the point of anguish; this in turn has caused a great deal of satisfaction among President Donald Trump’s supporters in the media, who may have been just as surprised but weren’t going to let that get in the way of their enjoyment of the furore. Once again, everyone has been caught napping – sedated by the earlier lie that the existing fabric of the building would not be compromised to make way for Trump’s plans.

But the destruction was also strangely obvious. It was logical, although that logic is purely Trump, not that of the American presidency. Trump’s plans for the site are for a $250 million, 8,400 square metre ballroom, bedecked in glitz. The ambition, the superlatives, the more-is-more decor, the hospitality-industry instinct, the rapid and unauthorised removal by heavy machinery of any inconvenient obstacles and the greasy layer of bluster and deceit helping everything along – these are all Trump’s defining characteristics. Now that the initial shock has subsided, the real surprise is that Trump didn’t do something similar in his first term. Indeed, in that first term he appeared oddly late to the architectural potential of his presidency – his executive order on Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again came right at its tail end, in 2020. Now he is making up for lost time and will not be observing bureaucratic niceties. So, goodbye East Wing.

The plume of reaction that rose from the rubble contained numerous absurdities. It has been amusing to watch Trump’s supporters suddenly, unanimously decide that the East Wing was no more than a dilapidated outhouse, an embarrassment that was long overdue for replacement. Equally silly has been some of the rhetoric from those angered by the demolition, comparing the act to the destruction of ancient monuments by ISIS or the slashing of a Rembrandt. Most of the White House – even the historic residence – is much more recent than it appears. The residence was completely gutted during the Truman presidency and its total replacement was seriously considered. What is striking about the photos of the machines at work on the East Wing is the amount of rebar sticking out of the building. It was reinforced concrete, not bricks and mortar, as befits the surface structure of an underground bunker. But this concealed solidity did not save it in the end.

What really shocks is the brazen nature of the demolition, rather than anything special about what was demolished. No permission was sought; indeed, few seem to have been aware that it was even possible. The symbolism was on-the-nose. The experience of the Trump presidencies, both within the United States and outside it, has been the dissolution of various comfortable assumptions about American power. Those certainties have been eroding for some time, but here they have their visible emblem. The demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St Louis in 1972 did not mark the beginning of the end of modernist architecture in the United States, but rather the point at which a hidden process, the ebbing of confidence, became spectacular. It was an image to put on the covers of all the books, a visual metaphor. And so it is with the East Wing.

Pruitt-Igoe fits into the scene, as the demolition forms part of a feverish sequel to the architecture of the 20th century. The implosion of Minoru Yamasaki’s failed housing project became a powerful symbol for many reasons, not least thanks to the historian Charles Jencks and the film-maker Godfrey Reggio, who made it part of his visual essay on modernity, Koyaanisqatsi (1982). But a big contribution to this myth-making was made by its prominence in Tom Wolfe’s popular polemic against modernist architecture, From Bauhaus to Our House (1981). Wolfe’s argument in that pungent little book is more psychological than aesthetic. For Wolfe, it was inexplicable that international modernism should achieve hegemony in the most golden moment of the post-war golden age when the ‘energies and animal appetites and idle pleasures’ of Americans from high to low became ‘enormous, lurid, creamy, preposterous’. He continues:

The way Americans lived made the rest of mankind stare with envy or disgust but always with awe. In short this has been America’s period of full-blooded, go-to-hell, belly-rubbing wahoo-yahoo youthful rampage – and what architecture has she to show for it? An architecture whose tenets prohibit every manifestation of exuberance, power, empire, grandeur, or even high spirits and playfulness, as the height of bad taste. We brace for a barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world – and hear a cough at a concert.

Wolfe was never very sound on architecture – he fills several chapters with exceptions to the above blanket statement, such as Eero Saarinen, John Portman, Edward Durrell Stone and Philip Johnson, making it clear that it’s only Eurotrash such as Gropius, Mies and Corbu who got his goat. But he certainly knew animal appetites and wahoo-yahoo rampages. And Trump is the product of that era. Both his elections have been born of a semi-conscious impulse to return to that youthful rampage, often in the hearts of people who weren’t around to enjoy it first time around. This frantic yearning can be seen in most of the weather fronts currently buffeting the American attention, from the scattershot resumption of manned space exploration to the furore over the rebranding of Cracker Barrel.

The architectural argument on the right, as it has trickled down the generations, has less to do with the modernist style and more to do with the paranoid style, becoming a wicked conspiracy against the American people by the usual sinister, degenerate forces. Speaking to Fox News about the demolition of the East Wing, deputy White House chief of staff Stephen Miller said: ‘The scandal is how Democrats on the left have scarred the landscape of our country with grotesque so-called modern art that celebrates ugliness.’ Trump’s ballroom would be a 90,000 sq ft rebuke to that ugliness: ‘Very importantly, President Trump is making sure it is in the neoclassical design around which our nation’s architecture has long been directed. Up until again recently, where we begin seeing these modern art structures, these brutalist structures, and these many other buildings that have been horrible and depressing to look at.’

What to expect? The ballroom designs revealed so far have been vague in some specifics and Trump is a mercurial client. But ‘enormous, lurid, creamy, preposterous’ is likely to cover it. Neoclassical, in the hands of these connoisseurs, is a somewhat elastic term, generally used to mean ‘good, correct’ (just as brutalist simply means ‘bad, wrong’). We certainly won’t be dealing with the disciplined, archaeological grandeur of Karl Friedrich Schinckel or Henry Bacon, architect of the Lincoln Memorial. The heavily gilded renderings of ballroom interior owe far more to the baroque, even the rococo, than to Thomas Jefferson. It sits on the city limits between Las Vegas and St Petersburg. It is, quite simply, not the sort of thing democracies build.

What will prove more shocking than the demolition of the East Wing is the coming alteration of the entire appearance of the White House. The East Wing was not a precious building because it was designed to be largely invisible, screened out of views of the residence by landscaping, much of which is also being removed. The ballroom will be larger than the White House itself, yawping over its roof. Whatever neoclassical virtues it may possess, symmetry and balance will not be among them.

But we must watch what we say when mentioning symmetry. Among Trump’s other plans for Washington, D.C., is a triumphal arch on the other side of the Potomac river, facing the Lincoln Memorial. In photographs of Trump poring over models of this arch and its setting, the Lincoln Memorial appears to be rotated to face the arch, rather than the Mall and its own reflecting pool. This recalls a line from Deyan Sudjic’s book The Edifice Complex (2005): ‘On one occasion, Stalin was observed casually picking up a representation of the onion-domed St Basil’s cathedral from a model of the Kremlin to see how the city would look without it.’ Once Trump appreciates how lopsided the ballroom has made the White House, he may turn his attention to the West Wing.