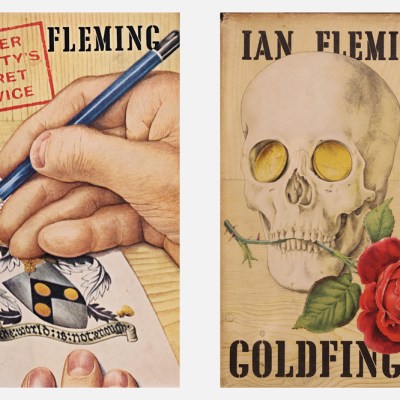

The name Denis Wirth-Miller is invariably coupled with that of his lifelong partner, Richard Chopping, and their close friend of many years, Francis Bacon. While Chopping achieved success and fame with the dust-jackets he designed for Ian Fleming’s James Bond books, and Bacon is widely acclaimed as one of the greatest painters of the 20th century, the work of Wirth-Miller (1915–2010) has until recently remained little known. It has not helped his reputation that he and Bacon often worked closely together, at times pursued similar subjects and in a few cases, even seem to have worked on each other’s paintings. Instead, Wirth-Miller has been unfairly dismissed as a pale imitation of his sometime collaborator. It is good to report that a major survey at Firstsite in Colchester conclusively demonstrates that Wirth-Miller was not only an artist in his own right, but also a very fine one who deserves to be much better known.

Rain (1976), Denis Wirth-Miller. © The Estate of Denis Wirth-Miller

Born in Folkestone, Kent, to an impoverished German hotelier and his English wife, Wirth-Miller showed an early talent for drawing and painting. He left school at the age of 15 and got a job in the design department of the Manchester textile manufacturer Tootal, Broadhurst and Lee. After a year he asked to be transferred to the company’s London office and set about joining the capital’s artistic and sexual bohemia. He moved into Walter Sickert’s old studio in Fitzrovia and dedicated his spare time to improving his skills as a painter. In 1937 he met Richard Chopping, who had worked for an interior design magazine, then embarked on a course in stage design. The two men entered a lifelong and notoriously combative relationship and became part of the Fitzrovian set alongside other queer painters such as John Minton and the Roberts Colquhoun and MacBryde. When war broke out they decamped to a small cottage in the Stour Valley, where they were befriended by John and Christine Nash. Among the earliest paintings in the Firstsite exhibition is Watercolour After John Nash (undated), while Stour Valley Landscape (1939) bears some resemblance to the work of Nash’s brother Paul.

Installation view of ‘Denis Wirth-Miller: Landscapes and Beasts’, 2022, Firstsite. Photo: Richard Ivey

Wirth-Miller then decided that both he and Chopping should enrol at Cedric Morris’s East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing, where they did odd jobs in exchange for tuition and met Lucian Freud, with whom they briefly became close before experiencing the kind of major falling out that characterised the lives of all three artists. After leaving the school they became temporary house-sitters in a huge, run-down manor in Essex, ideally situated for Wirth-Miller to develop his skills as a landscape painter. While there they collaborated on a children’s book, Heads, Bodies and Legs, which became a huge success when it was published in 1946. They made frequent excursions to London, where in late 1944 Wirth-Miller (who always maintained he was set up by the police) was arrested for gross indecency and sentenced to nine weeks’ imprisonment.

The two men had meanwhile bought the Storehouse, a dilapidated but beautifully situated property on the banks of the River Colne at Wivenhoe. They moved in a few months after Wirth-Miller emerged from Wormwood Scrubs and lived there for the rest of their lives. The Storehouse provided Wirth-Miller with inspiring views to paint and their friends with a riparian Fitzrovia where they could carry on the kind of drunken revels they enjoyed in London. The most regular visitor was Bacon, to whom they had been introduced by the Roberts, and he more or less became part of the household, often working in the studio there. Wirth-Miller had by now begun exhibiting his paintings in London galleries with some success, and by the 1950s would shake off the influences of the Nashes, and of the Neo-Romantics, seen in the paintings he did of Welsh landscapes during the previous decade, to produce something entirely new both in vision and technique.

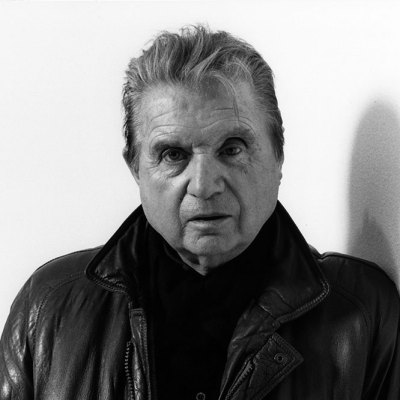

Denis Wirth-Miller, photographed by Francis Goodman (1971). © The Estate of Denis Wirth-Miller

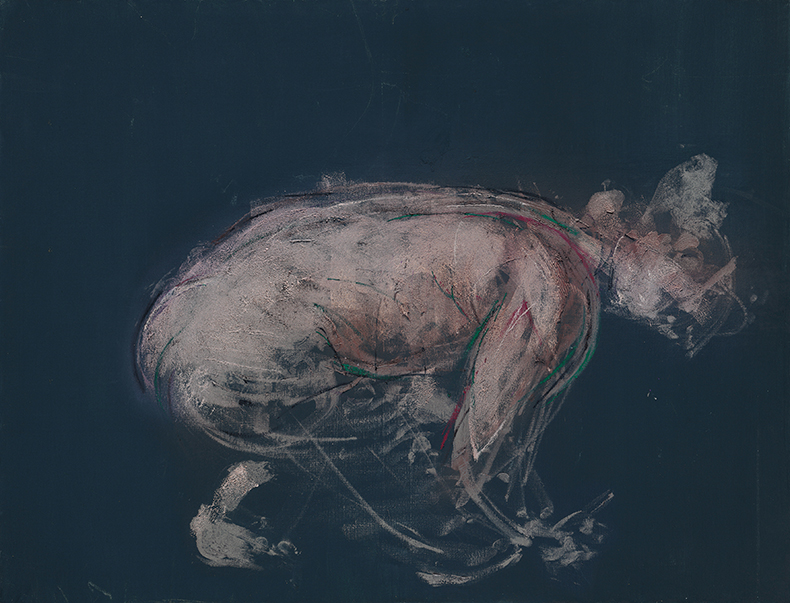

His landscape paintings are almost entirely devoid of human or animal figures, but at the same time he was also making intensely dynamic studies of dogs and other ‘beasts’, including crouching or wrestling men. Inevitably, these paintings have been compared with those of Bacon, notably by David Sylvester who in a review in the Listener declared that ‘an idea of Francis Bacon had been re-stated in a rather neon-lit way’. Though Wirth-Miller is often characterised as a disciple of Bacon, Andrew Wilson in his contribution to the excellent exhibition catalogue convincingly argues that the relationship between the two painters was more mutually dependent. Bacon frequently worked alongside his friend and discussed work-in-progress with him. Crucially, it was Wirth-Miller who first ‘discovered’ Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs of humans and animals in motion, and who in 1949 introduced Bacon to images that had a profound influence on the work of both artists.

Crouching Figure (1955–56), Denis Wirth-Miller. © the Estate of Denis Wirth-Miller

The two painters were also clearly drawn to the bestial nature of animals and human beings – the exhibition at Firstsite devotes a whole wall to Wirth-Miller’s studies from around 1953–54 of solidly muscular dogs, any one of which looks capable of seeing off Bill Sikes’ fearsome Bull’s Eye. Although some of these studies are derived from Muybridge, one wonders whether Wirth-Miller was also familiar with the many drawings of ferocious or down-at-heel dogs by Honoré Daumier, who was one of Bacon’s favourite artists. In a separate room Wirth-Miller’s paintings are hung alongside several by Bacon. Wirth-Miller emerges very well indeed from this juxtaposition – though it should be admitted that his case is helped by the inclusion of one of Bacon’s very worst paintings, the garish and slovenly Study for Portrait of Van Gogh VI (1957). While Wirth-Miller’s Study of a Dog in Movement: Leaping (1953–54) could at first glance be mistaken for a work by his fellow artist, not least because of its blue and buff background, the overall composition is very different from Bacon’s celebrated Dog (1952), which hangs near it. As with his caged monkeys, Bacon’s canines seem trapped – pacing a green circle in Dog, while cars speed by in the distance, or attached by a leash to a shadowy owner in Man with Dog (1953) – whereas Wirth-Miller’s freely walk, trot or bound along, their tails whisking behind them, apparently captured just as they are about to leap out of the picture plane. These paintings are all about movement, swirling brushstrokes skilfully mimetic of sheer animal energy. In Shaking Dog (1954), for example, white lines dashed all over the dark outline of the dog not only suggest water flying from a violently agitated pelt, but also the precarious stance and instability of the animal’s legs as it performs this action.

Study of Dog in Movement 2 (1953), Denis Wirth-Miller. © the Estate of Denis Wirth-Miller

In the article already quoted, Sylvester stated that even in Wirth-Miller’s landscapes ‘a broad hint has been taken from Francis Bacon’, a suggestion that he does not elaborate upon and seems inexplicable unless motivated by simple malice. Small wonder that Wirth-Miller slapped the critic when he next encountered him, whereupon Sylvester punched him back, breaking the artist’s nose. Wirth-Miller was inclined to such confrontations, particularly when drunk (as he frequently was), but one can see why he was infuriated, especially because Sylvester’s summing-up on him as ‘an essentially derivative painter’ would stick.

In fact the landscapes to which Wirth-Miller largely devoted the rest of his career are not in the least derivative of anyone but instead highly distinctive. Several of the paintings in the exhibition depict the estuarine countryside of Essex, a local landscape of marshes and reed-beds to which he often returned as a subject, but he also painted other parts of East Anglia and made excursions to Dartmoor. Many of the Essex paintings show a flat landscape stretching away in layers of colour to a distant and largely featureless horizon, with the contrasting vertical stripes of reeds taking up the foreground. The occasional line of trees can be seen – bare-branched and painted with an etching-like delicacy in the beautiful Estuary Landscape Winter (1967–68), or in leaf and created from seemingly casual swirls of khaki paint in the bravura Reedbed with Small Wood (1959). The Dartmoor paintings similarly emphasise a wide horizon, with thin lines of carefully graded colour painted across the entire width of the canvas.

To appreciate the quality of these paintings, one really needs to stand before them, as they do not reproduce well. Photographs flatten their complex textures, fail to pick out their painterly detail and freeze the sense of movement that often characterises them. In Reedbed with Small Wood, for example, the background is painted in earthern colours so thinly that the texture of the canvas is visible, while the reeds are vertical lines that, though narrow, are made three-dimensional by the thick application of paint, so that they look like slivers of gathered fabric. A similar technique ingeniously and convincingly creates the lines and layout of the fields beyond. As for movement, Wirth-Miller based many of his landscapes on photographs he took at random through the car window while being driven by Chopping through the countryside. Three paintings of a country lane from the early 1970s give a remarkably vivid impression of speeding towards a bend in a road lined with high hedges and an overhanging canopy of trees, while lines smeared across Wet Evening Landscape (1962) evoke not only a heavy downpour but the ineffective sweep of windscreen-wipers. Weather plays a significant role in most of Wirth-Miller’s landscapes, which tend to be darkly brooding or subject to pelting rain and howling winds, beautifully conveyed. Thin, horizontal slashes of paint blur the dark green outlines of trees to suggest a gusty day, while dashed vertical lines all curving in the same direction become wind-bent grasses and reeds. The energy that has gone into such pictures is palpable, giving them an extraordinary immediacy. These landscapes do not belong to any gentle English pastoral tradition of painting but are instead thrillingly elemental.

Gust of Wind (1970–71), Denis Wirth-Miller. © The Estate of Denis Wirth-Miller

While by the mid 1970s Wirth-Miller’s reputation as a painter had remained steady, that of Francis Bacon had reached giddy heights. Success had not improved Bacon’s bad behaviour, and in 1977 he drunkenly mocked and condemned as ‘rubbish’ the work his friend had assembled for an exhibition at the Wivenhoe Arts Club. Wirth-Miller decided that his career was over: he closed the exhibition, destroyed most of the work and hardly ever painted thereafter, though some pictures were included in a group show the following year. His paintings were never exhibited again until the year after his death, when the Minories in Colchester held a retrospective. Without his painting, Wirth-Miller found it hard to fill his days and he increasingly turned to drink. He and Chopping became famed less for their art than for their furious rows, which often took place at other people’s houses, making them unwelcome dinner guests.

Their declining years were increasingly grand guignol, but none of this should detract from their considerable achievement as artists. Chopping was given his due in an exhibition at the Salisbury Museum last year, and now it is his partner’s turn. Firstsite has mounted a survey of more than 100 works that more than justifies its size and makes Lucian Freud’s characteristically vindictive habit of referring to the artist as ‘Denis Worth-Nothing’ look very silly indeed. Most of these outstanding paintings and drawings are in private hands, and so this beautifully mounted exhibition provides a rare opportunity to see them – an opportunity that no-one who is interested in 20th-century British art should miss.

‘Denis Wirth-Miller: Landscapes and Beasts’ is at Firstsite, Colchester, until 22 January 2023.