Jenners in Edinburgh stands on a corner of Prince’s Street, opposite the towering Gothic Revival monument to Sir Walter Scott. Almost as much an institution as the Scots bard himself, until 2005 Jenners held the accolade of being the oldest independent department store in Scotland – and one of the oldest in the world continuously trading from the same site, which it had done since 1838. Confidently rebuilt in the late 1890s after a major fire, the exterior offers a masterclass in Victorian eclecticism. Jenners (by then owned by the House of Fraser) closed in 2020, and is now under new ownership. David Chipperfield Architects have embarked on a refurbishment, which will draw on the pattern of the Victorian original when the old department store was essentially a series of internal shops. A new hotel occupying the building’s top storeys will now help to secure a future for Jenners. Given its location, looking out and up towards the castle, and its centrality to both Old and New Towns and Waverley railway station, this may well be one of the most well considered of such heritage-led transformations anywhere.

The Victorian facade of Jenners on Princes St, Edinburgh. Photo: Manuel Velasco via Getty Images

The Chipperfield visualisations suggest an engaging series of covered arcades leading to a soaring central atrium at its heart, referred to by the architects as a ‘grand saloon’ and functioning as an elegant public space which unites the store and the hotel with the city on Princes Street and St Andrew Square behind. The emphasis is on lightness, in tone and detail. The impression is Parisian, though the building will present new elevations to the existing 1960s and 1970s extensions, tempering the retro mood. In the meantime, should anyone question where the cool Chipperfield aesthetic has gone, the practice can also be found at work nearby at the Dunard Centre, a new medium-sized concert hall which will be inserted behind Dundas House on St Andrew Square, transforming a key section of the Georgian New Town.

It could be a year in which Edinburgh, with these two projects on the starting blocks, shows up London. The arduous business of persuading Marks & Spencer that its (unlisted) Marble Arch flagship store deserved retrofit rather than demolition recently entered a new round when Angela Rayner overturned her ministerial predecessor Michael Gove’s decision to retain it. The chunky sub-art deco store and the wider site is now facing redevelopment. The wrangle may determine the future of an entire shopping zone, in this case western Oxford Street. It has pitted conservationists (led by SAVE Britain’s Heritage), energy specialists and structural engineers with expertise in sustainability against mainstream professionals. For those newly qualified and freshly entering the UK profession, whether the picture looks like one of enormous possibilities or a period of stasis has yet to be determined.

In North Jutland, meanwhile, the practice group known as BIG – the initials of Denmark’s favourite architectural son, Bjarke Ingels – is indulging in a feisty reimagining of a redundant out-of-town supermarket. In 2018 the small-scale Museum for Papirkunst was founded in Blokhus by psaligraphist Karen Bit Vejle, aiming to be a Scandinavian-wide study centre for paper art and design. The success and potential of the enterprise soon pointed to something altogether bigger. The outcome has been to more than double the floor area of the unexceptional building at the heart of the site. Everything rests on the forms of the roof. There is something of the art of folded paper, if not quite origami, in the swooping lightweight structures that signal the arrival of the new centre, which will incorporate workshops, educational facilities and more. The aim is to secure for the building the highest possible certificate of sustainability – platinum.

Bjarke Ingels Group’s concept for the new Museum for Paper Art in the north Jutland region of Denmark. Image: Wizarch

Scandinavia and the neighbouring Baltic countries have long been driven by good practice in environmentalism and sustainability. In Sickla, south of Stockholm, Wood City is due to open this year. Designed by Danish and Swedish practices, respectively Henning Larsen and White Arkitekter, it offers commercial and residential buildings which are 100-per-cent timber-built. As if to encapsulate the mood in these more enlightened countries of northern Europe, this autumn Copenhagen is hosting that congenial city’s inaugural architecture biennale, with a theme of ‘slow down’.

An impression of housing in Stockholm Wood City in Sickla, the world’s largest urban development project in wood. Image courtesy Atrium Ljungberg

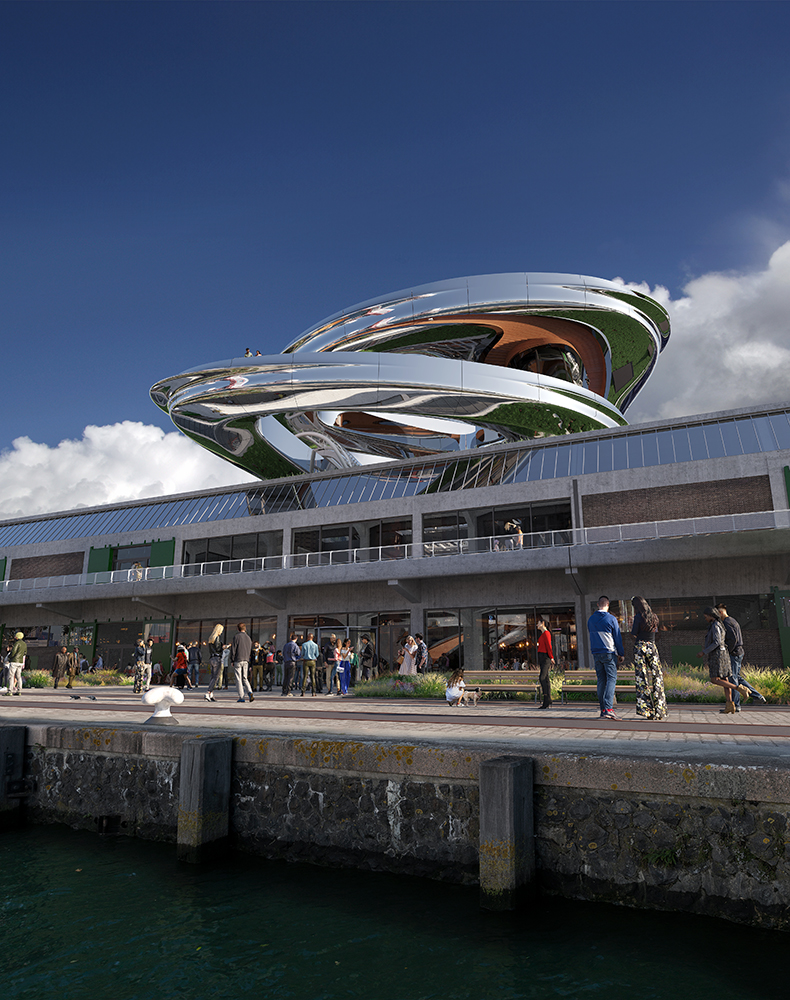

The movement of peoples is, of course, an area of interest for every one of these countries. The Netherlands, so densely populated and now politically febrile, will see the opening on 16 May of the Fenix in Rotterdam, a museum of migration based in and around an immense 1920s riverside warehouse built to serve the needs of the clients and passengers of the Holland America shipping line. At its centre the Chinese architectural practice MAD has designed a spiral staircase in the form of a huge steel tube; resembling a water shute at a 1980s leisure centre, it scrolls up and around the roof and has been named ‘the Tornado’. In a decade in which architects have forsaken styles and isms, there are pervasive tropes, one of the most pervasive being the rooftop squiggle. Let’s hope it goes out with the decade.

Artist impression of the Fenix in Rotterdam, designed by MAD Architects. Image: Proloog.tv

While Antwerp’s Red Star Line Museum set the standard for presenting the topic of mass emigration (essentially one way to New York), the theme is a challenging one. Constant news stories about people smuggling, and images of bodies and possessions left washed up after failed boat crossings, have augmented populist sentiment in the EU and elsewhere. In the UK, Liverpool’s International Slavery Museum and its companion Maritime Museum have this month closed their doors for maintenance and potential redevelopment – the programme ‘subject to funding’. London’s Migration Museum has for the last few years been housed in Lewisham Shopping Centre, but plans to move in the next year or so to 65 Crutched Friars, a new development in the City of London.

As much as any boardroom in the world of retail, the City of London is scratching its collective head about the future, the effects of new work patterns and an uncertain economic outlook, and thus the viability of the existing and pending fabric of the Square Mile. Smithfield meat market has had its marching orders but is no longer heading to Dagenham. The only parties with clear confidence in Smithfield as it stands are those installing the London Museum (the former Museum of London), now less than two years away from opening in a resplendent Smithfield structure. Yet the wider City of London feels hydra-headed. The tensions are expressed by the Corporation planners’ attempts to nip and tuck a soaring office block (One Undershaft) by the practice headed by the architectural academic Eric Parry, while Bevis Marks Synagogue, which opened in 1701, is menaced by the loss of light and crowding that a rebuilt tower on its boundary will bring. Even the highly contested redevelopment above Liverpool Street station is still live, despite a change in architects and developers.

Architecture elsewhere is dealing with real life, rather than wrangling over plans. Seen from the sparkling nave of the renewed Notre Dame in Paris or the fringes of south Asian mega-cities, worries about carbon capture and scarce resources must seem less urgent. But if this is fiddling, Rome in 2025 is drowning rather than burning. In anticipation of the human tide that the papal Jubilee has unleashed on the city, the piazza in front of San Giovanni in Laterano has been primly landscaped in turf and stone – an effect more Parisian than papal; but perhaps offered as a symbolic ecological nod.