In The Last of England, a collection of autobiographical sketches, diary entries and script notes published in 1987, Derek Jarman offered a ferocious state of the nation address:

Young bigots flaunting an excess of ignorance. Little England. Criminal behaviour in the police force. Little England. Jingoism at Westminster. Little England. Small town folk gutted by ring roads. Little England. Distressed housing estates cosmeticised in historicism. Little England. The greedy destruction of the countryside. Little England.

It’s a passage that encapsulates many of Jarman’s most persistent concerns: national identity, reactionary politics, the representation of the past, architecture, landscape and ecology. Its acerbic tone echoes the anger of Jarman’s film The Last of England, also released in 1987, a violent, beautiful collage of mythological sequences. We meet a horned dancer circling a fire to a soundtrack of gunfire and disco. We witness an ambiguous sexual encounter between a terrorist in a balaclava and a naked yuppie, staged on a massive Union Jack strewn with cigarettes and empty bottles. We’re hypnotised by Tilda Swinton dancing in a wedding dress on a desolate beach. In both its written and cinematic forms, The Last of England brings together histories of empire and monarchy with queer politics and anti-Thatcher rhetoric. The results, like so much of Jarman’s prodigious output, still feel indefinable yet deeply informed by British, and especially English, culture. How might we reassess these words, images and sounds in today’s charged political climate?

This year marks 25 years since Jarman’s death at the age of 52 from Aids-related illnesses. The occasion has generated a flurry of events. In February, English Heritage unveiled a blue plaque commemorating Jarman at Butler’s Wharf on the south bank of the Thames near Tower Bridge, where the artist had a warehouse studio between 1973 and 1979. Other activities have included the release of new Jarman boxsets by the BFI and the reissuing of key texts by Vintage Classics, while a screening programme at the Void gallery in Derry begins in November. Earlier this year, too, I organised a panel discussion celebrating Jarman’s life and work at Tate Britain.

Most eagerly awaited is ‘PROTEST!’, an exhibition at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (15 November–23 February 2020), which includes paintings and collages, theatre and set designs, pop videos and gardening, alongside film-making and writing. The scope of Jarman’s work might be a daunting prospect for a single exhibition, but considering these diverse elements alongside each other seems essential. As the journalist Jon Savage has pointed out, ‘There are so many Derek Jarmans that it feels strange to focus on just one aspect of the man.’

Derek Jarman (1942–94), photographed by Trevor Leighton in 1990. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, London; © Trevor Leighton

Derek Jarman was born in Northwood, Middlesex, in 1942. By his own account, he was ‘a nice middle-class boy’, the son of a brusque RAF officer from New Zealand. Jarman’s childhood involved spells in Italy and Pakistan, but it was a pivotal episode at a Dorset boarding school that provoked what he described as ‘my first confrontation with oppression’. Caught in bed cuddling and giggling with another nine-year-old boy, Jarman was whipped as punishment and denounced in front of his classmates. ‘The terrible battle with family virtue was on,’ he later declared.

From the outset, Jarman’s identification as queer was closely tied to his creative energies. ‘I was set apart, a childhood observer who never joined in,’ he recalled. ‘All my energy was devoted to painting while the other boys learned their four-letter vocabulary on the rugger pitch.’ From 1960 to 1963, he took an undergraduate degree at King’s College London, studying English, history and history of art, attending architectural lectures by the legendary Nikolaus Pevsner, and discovering queer literary icons such as William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Jean Genet. Possibilities, both erotic and artistic, were rapidly expanding, and a summer in North America in 1964 was marked by sexual adventures. The Slade was Jarman’s next step, for a fine-arts degree completed between 1963 and 1967, during which time he designed sets for plays, ballets and operas, and immersed himself in the history of cinema.

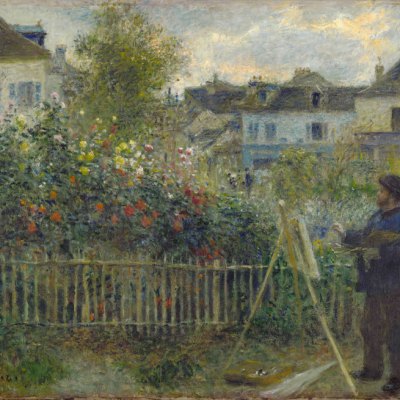

Painting, though, remained Jarman’s primary concern in this period. The early works in the IMMA exhibition reveal a shifting range of styles. Lowry is the obvious model for the anonymous urban figures of We Wait and Wait (1960–61), which earned Jarman a student prize, while Inspiration of the Poet (c. 1965) reworks Poussin. By contrast, the sharp minimalist landscape and geometric lines of Cool Waters (1966–67) hold a more American edge, and its inclusion of an actual tap and towel rail suggests a knowing Pop collage.

It’s fascinating to compare these uncertain beginnings with the boldness, confrontation, political potency and dark humour of the art Jarman created in the 1980s and ’90s. Take the GBH series he made for a retrospective in 1984 at the ICA, London. These six large works, each nearly ten feet tall and almost eight feet wide, draw on Rothko and Goya in their fiery red, deep black and glowing gold patterns of paint laid on newspapers. In each painting, an outline form of Britain is visible amid the flames, while a circle drawn over the landscape suggests the country is under attack. Nuclear annihilation, civil unrest, a grand historical fall: the series allows for multiple readings, while the initials of the title have been interpreted as ‘Great British Horror’ or ‘Great Britain Holocaust’. The series bridges the two most apocalyptic renderings of national destruction Jarman created on film: Jubilee (1978) and The Last of England.

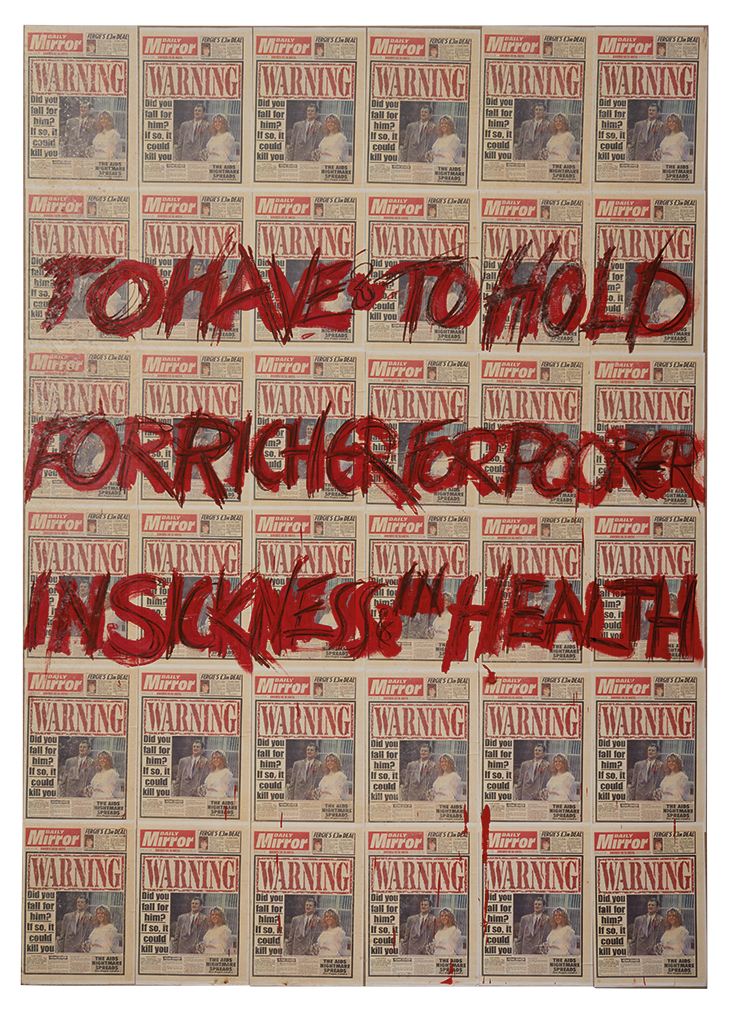

To Have and to Hold (1992), Derek Jarman. Courtesy Irish Museum of Modern Art/Amanda Wilkinson; © The Keith Collins Will Trust

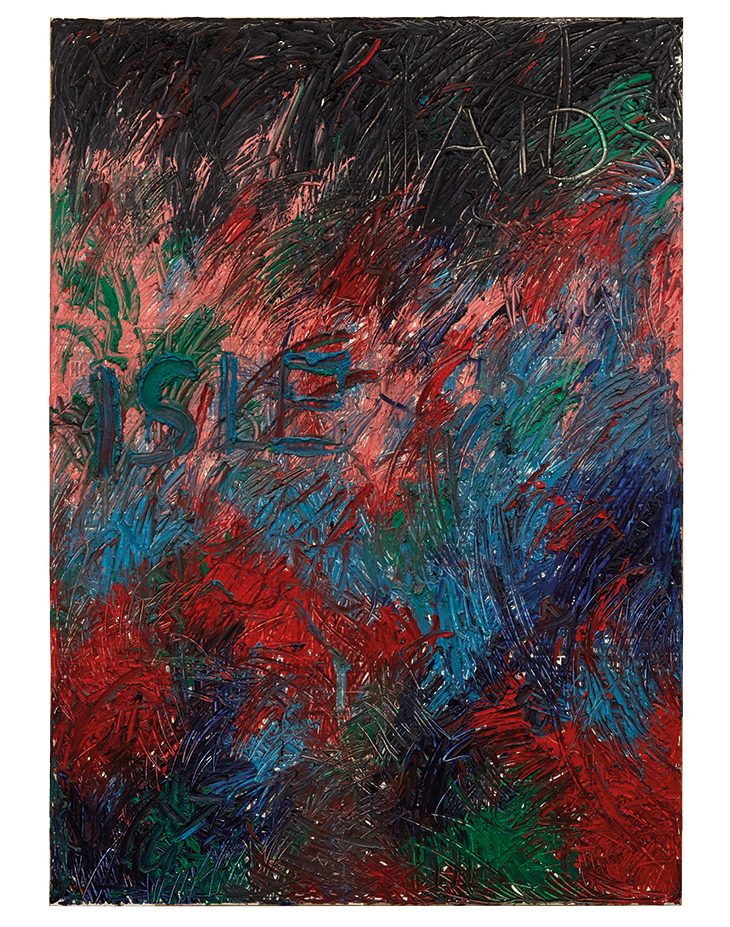

In paintings such as To Have and To Hold (1992), Jarman combined rows of homophobic tabloid stories with defiant scrawled slogans. In the final two years of his life, statements that ironically reflected upon his declining health were smeared by hand into thick layers of colour, in paintings such as Aids Isle (1992), Fuck Me Blind (1993) and Dead Sexy (1993). The contrast with the ’60s work is stark: from respectful, considered engagements with art history to fast, direct barbs aimed at reactionary forces. Another line from The Last of England (the book) captures this mood: ‘Since I’m obviously in the cesspit, I’ve nothing to lose: I’m out to destabilise and destroy.’

A partial hiatus in painting during the 1970s can be explained by Jarman’s discovery of film-making. He began working with a Super 8 camera in 1970, and in the following decade made dozens of home movies, capturing life in his London studio, the changing landscape of London and trips to mythical sites around Britain. The format allowed Jarman to experiment with different techniques, speeds and colours. ‘My first films filled in the empty spaces of my painting, then I lost heart with the painting,’ he explained. By the time he returned to the canvas with vigour in the 1980s, Jarman seems to have adopted an approach first developed in his film-making: the emphasis now lay on how he was working, rather than the final product. By the mid 1980s, with raw materials visible and pronounced brushstrokes, he was insisting that in painting, ‘It’s all about the process, I want people to notice the process.’ Similarly, in a journal of 1989, he provides a reminder of his creative ambitions: ‘The filming, not the film.’

Aids Isle (1992), Derek Jarman. Courtesy Irish Museum of Modern Art/Amanda Wilkinson; © The Keith Collins Will Trust

Evidence of his methods can be found in his sketchbooks, many of which now sit in the BFI National Archive. Often bought in bulk on trips to Italy and with covers customised with black paint and gold marker pen, the books contain photographs, cuttings, drawings, collages, poems and scripts. Each film project has a dedicated album, indicating how the director’s thoughts gathered and evolved before shooting began.

Jarman’s shoots were renowned for their sense of camaraderie. Toyah Willcox, who starred in Jubilee, said, ‘the whole thing about Derek was that he allowed everyone to learn. He was the most fantastic teacher. There was no elitism, there were no closed doors.’ The emphasis placed on collaboration, thrift and imagination was partly a matter of necessity. For the majority of his career, his films had tiny budgets, though public money from the BFI and Channel 4 was forthcoming from his fourth feature onwards. Jarman’s cinematic ambitions were, however, constantly hindered by battles with producers and funding bodies. ‘The money required to make a film, let alone a consistent cinematic career, can evaporate like snow in June,’ he noted.

Punk icon Jordan (Pamela Rooke) appears as the ‘anti-historian’ Amyl Nitrate in Derek Jarman’s film ‘Jubilee’ (1978). Courtesy BFI; © Basilisk Corporation

Shot around decaying warehouses, abandoned homes and grassy wastelands in Southwark, Rotherhithe and the Docklands, Jubilee is a fantastical vision of an anarchic, apocalyptic capital. The punk protagonists’ ability to improvise with meagre resources mirrors the collective ethos and ingenuity Jarman instilled in his own shoots. Here, the energy of the film-making process is clearly evident in the film itself. Alongside the violence and dereliction in Jubilee, there’s plenty of singing and dancing. Jarman’s desire to disrupt establishment iconography is again visible with ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘Jerusalem’ reimagined for the revolution, while Buckingham Palace is turned into a recording studio and Westminster Cathedral becomes a disco. Though Jubilee is too unruly for easy political comparisons, its gleeful destruction of oppressive nationalist myths, the currency of Little England, resonates strongly in a Brexit context. How these images are received in contemporary Dublin will add another dimension to the IMMA exhibition.

Jarman, however, did not share punk’s desire to annihilate the past, and drew heavily on the English cultural canon. His feature films include imaginative adaptations of Shakespeare (The Tempest, 1979) and Marlowe (Edward II, 1991), while the work of Benjamin Britten and Wilfred Owen underpins War Requiem (1989). The artist Tacita Dean, who was a student at the Slade when she met Jarman in 1990, has described him as an ‘English alchemist’ with ‘a really particular English sensibility’. In this respect, Jarman’s capacity to rework and playfully subvert the nation’s most familiar cultural texts still offers a way forward for artists and film-makers today. His response to Little England was to engage with the nation’s past critically, rather than comprehensively reject it.

Jarman’s interest in history was by no means limited to Britain’s past. Sebastiane (1976), his first feature, is a tale of desire and martyrdom set among the personal guard of a Roman Emperor. Caravaggio (1986), the product of 17 scripts, countless funding woes and a decade of delays, self-consciously highlights its recreation of Renaissance Italy by including a calculator and typewriter amid the candles, daggers and oil paints. It’s emblematic of Jarman’s ability to bridge historical eras while avoiding the clichés and falsity of costume drama.

Pages from the notebook Derek Jarman kept in 1985 for the making of ‘Caravaggio’ (1986), including a reproduction of ‘St John the Baptist in the Wilderness’. Courtesy Derek Jarman Special Collection – BFI National Archives/Thames & Hudson; © 2019 The Keith Collins Will Trust

Another temporal jolt occurs when we assess Jarman’s vision of architecture, landscape and ecology. His studios of the 1970s, which included spaces in three different warehouses close to the Thames, represent a form of communal creative living no longer available to artists priced out of central London. Jarman’s ability to sense and capture urban change means that his Super 8 footage and a film like Jubilee now act as historical documents laced with sadness as London continues to lose spaces for artistic experimentation. Indeed, Jarman’s work is filled with reflections on what’s been lost in our built and natural environments. In the book, The Last of England, he laments, ‘I watched the industrial machine destroy the ecological fabric, I saw the poisons running through the rivers and the forests dying, the atmosphere changing.’ Reflecting on the so-called ‘golden’ years of post-war Europe, he admits, ‘we were living at the expense of the others, of the planet itself, so that there was always a feeling of guilt.’ His memoir Modern Nature (1991) records government seminars on global warming alongside the progress of his roses – indicating both a macro- and micro-scale attention to the environment that anticipates the eco-consciousness of contemporary artists addressing our climate emergency.

Many observers see Jarman’s legacy as embodied by the beautiful simplicity of Prospect Cottage, the timber fisherman’s house in Dungeness that he bought in 1986. It sits on a shingle beach with unique flora and fauna overseen by a nuclear power station; the flint formations, wooden sculptures and diverse planting Jarman created around the cottage still attract admirers. The musician Neil Tennant calls this garden ‘possibly his most “Jarman-esque” creation’. With alchemy and improvisation, Jarman reworked a most characteristic emblem of Little England – a garden in Kent – so that it becomes romantic and heraldic.

To my mind, though, it’s Blue (1993) that represents Jarman’s greatest achievement and a high point of recent British culture. Here, we experience an extraordinary fusion of Jarman’s passion for literature, music, painting and cinema. Blue consists of a single static shot of a glorious blue screen, a colour inspired by Jarman’s long-term interest in Yves Klein. The unchanging image also speaks to Jarman’s failing eyesight, to a sense of the void that shortly awaited him and, perhaps, to his father’s experiences patrolling the skies as an RAF pilot. Assembled by Simon Fisher Turner, the soundtrack includes music by the likes of Brian Eno and Erik Satie alongside a poetic collage of actors’ voices reading quotations from Jarman’s favourite writers and extracts from the artist’s diaries. Blue premiered at the Venice Biennale in June 1993, and was simultaneously broadcast that September on Channel 4 and BBC Radio 3. Tony Peake, author of an excellent Jarman biography, describes Blue thus: ‘Jarman had transmuted the pandemonium of images that had been his boon and bane into a vibrant void in which, miraculously, he was more fully present than in almost any of his other films.’

Installation view of Derek Jarman’s ‘Blue’ (1993), first shown at the Venice Biennale in June 1993. Courtesy Tate; © Basilisk Communications

Jarman’s legacy across different fields feels almost too extensive to catalogue. The film director Gus Van Sant, who met Jarman in 1986, has outlined his particular significance for queer culture: ‘Derek Jarman was a symbol of the future, of what my life as a film-maker would someday resemble. He was breaking new ground as an openly gay film director, and his politics and lifestyle were exciting new things to behold.’ Looking to artists’ moving image, Tacita Dean has suggested the pioneering importance of Jarman as ‘a painter working with film’. ‘Derek had a massive influence on me,’ she explains, ‘in terms of making me brave enough to just carry on working with film despite my context as a painter.’ There are also the many members of Jarman’s extended team who have gone on to develop their own celebrated practices, notably his former assistant Cerith Wyn Evans and John Maybury, who designed sets for Jubilee and later worked on The Tempest, The Last of England and War Requiem.

Beyond his status as an artistic innovator, it’s Jarman’s effervescent personality and the intertwining of his life, art and politics that appear to hold the deepest resonance for current practitioners. Jon Savage claims: ‘For Derek, everything was fused together in a kind of living Gesamtkunstwerk.’ Dean says the ‘quality of him as a man’ continues to inspire her. The writer Olivia Laing says she often asks herself, ‘What would Derek do?’ It’s a question we’d all be advised to consider as the forces of Little England.

‘PROTEST!’ is at the Irish Museum of Modern Art from 15 November–23 February 2020. The Last of England is included in the BFI Blu-ray box set Jarman Volume Two 1987–1994. Jubilee is released on DVD/Blu-ray by the BFI.

From the October 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.