From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It is easier to say who Diane Simpson is by defining what she is not. She is not a New York-based artist: she lives in a suburb of Chicago, where she has worked in a one-car garage for nearly 50 years. She is not a Chicago Imagist: though she studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) alongside that movement’s final wave, her concerns lie elsewhere. She is not a long-suffering mother who sacrificed her career for her family: she took time off from art school to raise three children but relished the opportunity to extend her education. And she was not overlooked: by the time she finished her MFA in 1978 she was already showing at Artemisia Gallery and over the next four decades continued to exhibit steadily. If the rest of the world needed time to catch up, that says more about which narratives get centred in art history than about Simpson herself.

‘Formal Wear’, a retrospective at the American Academy of Arts and Letters in New York, reveals a self-assured artist who found a satisfying formula for making art early on and gave herself ample time to develop it. Simpson begins with drawing: she creates meticulous axonometric projections on graph paper using a 45-degree angle, a system that allows her to resolve three-dimensional forms on a two-dimensional plane. During graduate school, she recalls making ‘very dimensional drawings’ that ‘just wanted to pop off the page’. Her specific interest was in how non-Western perspectival systems appeared in decorative arts – Turkish painting, Japanese scrolls, Persian miniatures. These traditions, championed at SAIC by instructors such as Whitney Halstead and Ray Yoshida, offered alternatives to Renaissance perspective, allowing multiple viewpoints to coexist simultaneously.

The high ceilings and herringbone-patterned parquet floors of the recently renovated Arts and Letters space provide an elegant backdrop for Simpson’s architectonic sculptures. The earliest sculpture demonstrates that straight out of graduate school Simpson had already achieved the alchemy she sought: transforming an ordinary, functional object such as a column into an abstract form. The column’s pleated surface suggests soft manipulation while remaining rigid and its skewed angles create a sense of spatial instability as you move around it. Simpson cut the interlocking cardboard pieces with a jigsaw on her dining-room table.

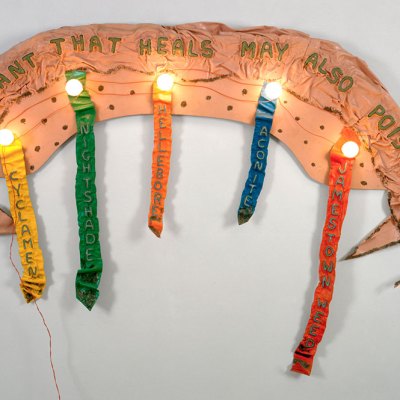

But her formation wasn’t solely about perspective systems and flat-packing techniques. She arrived at SAIC in 1968, just as the Imagist moment was waning and post-minimalist feminist practice was ascendant. By joining Artemisia Gallery she was supported by the feminist infrastructure that brought artists such as Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro and Joyce Kozloff to Chicago. She has said that ‘the women artists doing that work in the ’70s’ were the ones who spoke to her – artists such as Jackie Winsor, Eva Hesse, Mona Hatoum and Ree Morton, ‘primarily because they were working with […] non-art materials’. Morton, in particular, was an influential teacher. She used Celastic – a fabric-like plastic – to create decorative ribbons, garlands and banners that challenged the hierarchy between fine art and craft. Morton’s death in a car accident in 1977, as Simpson was completing her MFA, was a formative loss. There are compelling correspondences between the two artists: both transform soft, traditionally feminine sources (drapery, corsetry, aprons) into rigid sculptural forms, making decoration structural rather than applied.

The show at Arts and Letters combines drawings with sculptures. It’s a revelation to see the voluptuous curves of the sculpture Green Bodice (1985), made from painted MDF boards topped with a vinyl mesh sheath, and then see the drawing for this piece and discover that, exactly as the title claims, the source is a rigid 16th-century bodice. Such moments abound: Underskirt (1986), a ziggurat delicately engineered from thin strips of MDF and sheathed in cotton mesh, was based on an 18th-century metal frame for a skirt that was wide on the sides and narrow across the middle, while Formal Wear (1998), two chunky polyester geometric forms hanging from a wooden bar, was inspired by the cuffs in a Cranach painting. Simpson has never restricted herself to clothing: the show also includes Chaise (1979), in which a chair unfolds from the wall into the gallery, and Neighbor (2021), an unassuming Adirondack chair nudged askew.

Architects draft blueprints, dressmakers draw patterns. Simpson’s work exploits the overlap, creating forms that hover between the architectural and the sartorial. Her sources – Victorian corsetry, samurai armour, Amish bonnets, apron pockets – refer to the body through its deliberate absence. Conflating ‘feminine’ domestic arts with the ‘masculine’ work of architecture, Simpson narrows the artificially gendered gap between the two practices. But, frankly, any interpretation undercuts the essential attraction of her work: it’s just damn cool.

At the age of 90, she is at last receiving the major institutional recognition her work deserves. In 2018, the Hairy Who retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago paid renewed attention to the city’s art of the 1960s and ’70s, but Simpson’s work asks us to consider a parallel history for Chicago’s art scene, rooted in feminist reclamation of the decorative and post-minimalist material investigations. Now the Art Institute is presenting her first solo exhibition there: three newly commissioned works on the Bluhm Family Terrace, her first outdoor sculptures. The title comes from a note Simpson wrote on a series of rolled-up drawings from the 1980s: ‘Good for Future’. She has spent the past five years realising these decades-old visions. She based the drawings on architectural and design motifs seen during a trip to Japan, but the resulting sculptures have nothing noticeably Japanese about them. They are trademark Simpson: in paired colours such as avocado and robin’s-egg blue that evoke vintage fabric and torqued so that it is almost impossible to see both colours at once. Set against the stark Chicago skyline, the sculptures feel both like a homecoming and a vindication: proof that the world has finally caught up to an artist who was working at the highest level all along.

‘Diane Simpson: Formal Wear’ is at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, until 8 February.

‘Good for Future’ is at the Art Institute of Chicago until 19 April.

From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.