What’s in a name? For the dodo, if it could have understood human speech, a world of hurt. So-called father of taxonomy Carl Linnaeus dubbed the bird Didus ineptus, meaning ‘inept simpleton’, while the word ‘dodo’ is believed to come from the Dutch Dodaars, which means ‘fat-arse’. In 1598, a Dutch vice-admiral visiting its homeland of Mauritius named it Walghvoghel, meaning ‘tasteless’, ‘insipid’ or ‘sickly’ bird.

Of course, not everyone has agreed with such harsh judgements. Ralfe Whistler, the inventor of the litter-picker and the outdoor pub table, was a superfan: he inherited bones of the long-extinct bird from his ornithologist father, which sparked a lifelong passion. By the time of Whistler’s death last year, his home in Battle, East Sussex, was known as the Dodo House. He filled his nest with all manner of dodo-themed objects: paintings by the likes of Beryl Cook and Richard Bawden, sculptures, drawings, prints, letters, tableware, stamps, carpets, and even a toilet seat. ‘I wouldn’t say I am an eccentric,’ he once told the press. ‘But other people around here do, including my own family.’

A sculpture from the collection of ‘Dodo-ologist’ Ralfe Whistler; artist and date unknown. Photo: Summers Place Auctions

On 24 September, objects from Whistler’s collection will go on sale at Summers Place Auctions in West Sussex. What better occasion, Rakewell feels, to revisit some of the finest depictions of our late feathered friends in the history of art.

The Dodo and Other Birds (c. 1630), attributed to Roelant Savery. Natural History Museum, London

In this most famous of dodo depictions – often thought to be one of the very first – painted by the Dutch artist Roelant Savery in around 1630, several decades before the bird’s extinction – there is little trace of the sad self-awareness described in 1634 by the English diplomat Thomas Herbert, who visited Mauritius a few years earlier: ‘Her visage darts forth melancholy, as sensible of Nature’s injurie in framing so great a body to be guided with complementall wings, so small and impotent, that they serve only to prove her bird.’

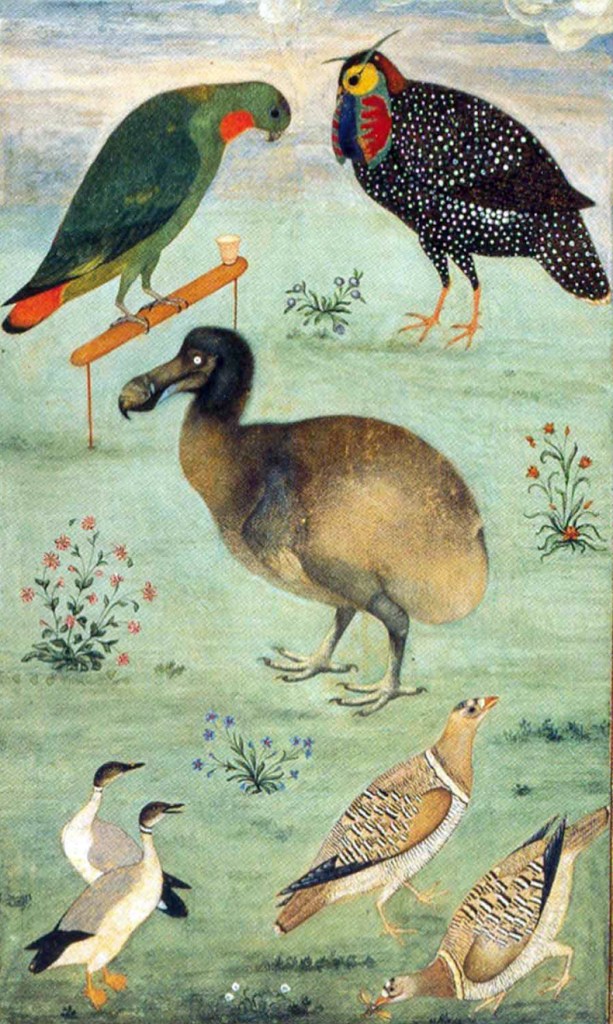

Untitled (1628–33), Ustad Mansur. Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Around the same time, the Mughal court artist Ustad Mansur also rendered the dodo in all its glory. He managed to instil the bird with a degree of gravitas notably absent from most paintings – perhaps thanks to the fact Mansur is thought to have painted from life, unlike Savery, who probably modelled his depiction on a taxidermied dodo.

Alice meets the Dodo (right) in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll, illustrated by John Tenniel. Photo: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

No discussion of the dodo is complete without mention of the radically egalitarian specimen in Alice in Wonderland (‘Everybody has won, and all must have prizes’). John Tenniel’s illustration of 1865 shows the moment after the assembled creatures have run their ‘caucus-race’: ‘The Dodo solemnly presented the thimble, saying, “We beg your acceptance of this elegant thimble;” and, when it had finished this short speech, they all cheered.’ Whether in life, death or Wonderland, Rakewell suspects that there are few things more cheering than a dodo.