Before he moved to Crete, before the sparkling light of the Mediterranean permeated his world view and his canvases, John Craxton painted rather more morose depictions of his native England. The artist was born in London to a cosmopolitan family, but from a young age lodged at his aunt and uncle’s house in rural Dorset where, if his early paintings and drawings are to be believed, he spent a lot of time wandering and sketching the landscape, immersed in his surroundings and his own thoughts. In early works he cuts a lonely figure – for it is difficult not to read his solitary shepherds and poets as self-portraits of some kind – among the ancient hills and gnarled trees, with only the birds for company. This brooding but lyrical vision of England won him recognition as a young talent in the neo-Romantic school – though like all good neo-Romantics he disliked the term. Craxton eventually strayed a long way from the fold, both geographically and stylistically, settling in Crete and pursuing a lighter and highly distinctive style. But the sense of being within a landscape – of drawing one’s own energies and emotions from its larger rhythms – that he established in chilly Cranborne Chase never left him or his work.

Poet in Landscape (1941), John Craxton. © Craxton Estate

Craxton’s reputation faltered towards the end of his life but was revived somewhat at the end of 2013, when the Fitzwilliam Museum mounted a retrospective at which his colourful Cretan paintings were a revelation. A number of these kaleidoscopic canvases are now on display at the Salisbury Museum (until 7 May), but the show – curated by Craxton’s biographer and executor Ian Collins, and on the second leg of a tour that started at the Dorset Museum in spring 2015 – is a decidedly more local affair. On view alongside examples of his major works are Craxton’s childhood sketches; a series of paintings by his uncle, Cecil Waller (all for sale); a selection of items from the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Farnham, whose collection fascinated Craxton as a boy (it closed in the 1960s); and a set of portrait drawings he made of local children that have only recently come to light. Craxton’s designs for cards and book covers (most famously for his friend Patrick Leigh Fermor) add a further note of personal domesticity.

Knowlton Church (1941), John Craxton. Private collection

This eclecticism makes for a less cogent show than the Fitzwilliam’s (which also benefitted from a simpler layout and higher ceilings than is possible in Salisbury’s 17th-century building) but the odd combinations do result in surprising insights. In the second of the main exhibition rooms, for example, are several paintings and drawings of rural landscapes and buildings (and a startling image of a dead hare on a tabletop, made when Craxton was living with Lucian Freud in London, which is an interesting diversion). They range from grey and moody visions in ink, to more controlled and colourful variations, including one, Alderholt Mill (1943–44), in which the house is painted in blocks of brilliant red, white and green. It’s an unexpected injection of colour that foreshadows Craxton’s later paintings (to which the curators have established a direct line of sight). It’s also a detail that is picked up in the bold wall colours selected for the display, which switch from a deep slate blue to brilliant yellow, marking Craxton’s departure for sunnier shores.

Alderholt Mill (1943–44), John Craxton.

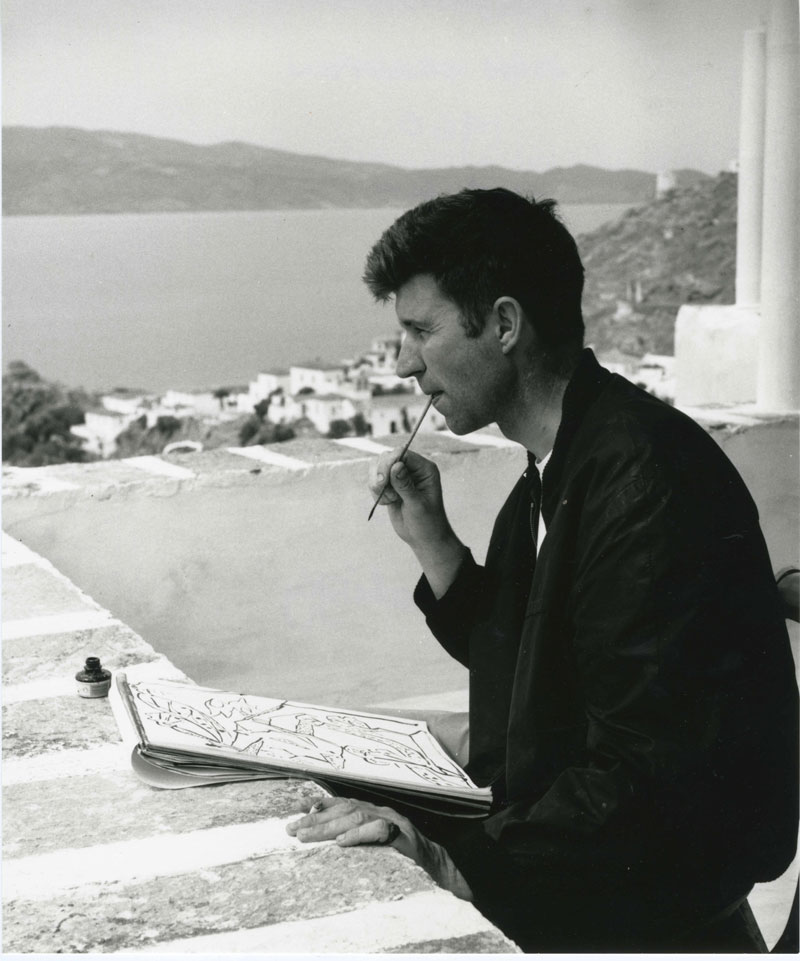

The artist’s first inkling that there might be a life for him outside the UK seems to have come from a visit to the Scilly Isles in 1945, after which he swiftly upgraded to the Mediterranean proper, travelling to Greece in 1946. Crete became a regular base for the artist, and while he did not officially relocate until 1960, the island replaced his home country in his affections quickly and completely. ‘I can work best in an atmosphere where life is considered more important than Art – where life is itself an Art’, he commented in 1948:

Then I find it is possible to feel a real person – real people, real elements, real windows – real sun above all. In a life of reality my imagination really works. I feel like an émigré in London and squashed flat.

John Craxton in Hydra, Greece, 1960. Photo: Wolfgang Suschitzky

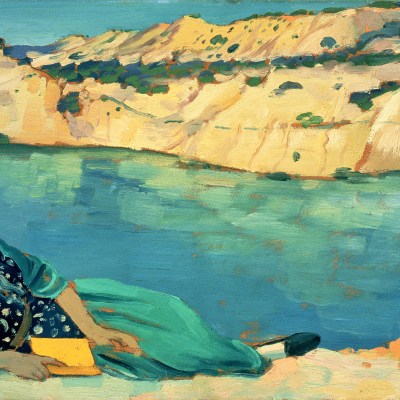

Craxton’s ambitious Four Figures in a Mountain Landscape (1950–51) serves as a centrepiece and turning point in the Salisbury display, which gathers several of his later paintings into its final two rooms. The large painting is an unashamedly Arcadian depiction of Aegean life, woven with colour, which encapsulates much of what changed in Craxton’s art after he went away. The smaller pictures surrounding it tell us a bit more about how and why his style evolved. Greek Fisherman (1946), made after his trip to the Isles of Scilly, but before he got to Greece, is an important reminder that the artist’s efforts to lighten his palette predated and probably inspired his first trip. He was already asking questions of his art – and was clearly predisposed to find his answers in the Aegean.

Two Greek Dancers (1951), meanwhile, reveals an important innovation that he would only make once he got there. The deceptively simple composition depicts two figures in outline against a pale grey-blue ground – but what astonishing outlines they are, changing colour as they feel their way around their subjects, indicating the local hues that have otherwise vanished into the airy surroundings. This technique recurs in various inflections throughout his later paintings, and few approaches so elegantly express both the hot, crystal clarity of the region’s light and the scattering, vibrating colours that it produces. Four Figures in a Mountain Landscape is, in reality, no more colourful than some of his British scenes: deep, dark blues and greens dominate the foreground as the sky turns to sunset overhead. But the whole thing is held together by silvery, shifting and vibrant threads of paint. They transform the image, laying down the memory of the warmth and brilliance of the day just ending, but also the expectation of another such day to come. You don’t see that in Dorset very often.

Four Figures in a Mountain Landscape (1950–51), John Craxton. © Craxton Estate. Photo: Bristol Museum, Galleries & Archives

‘John Craxton “A Poetic Eye”: A Life in Art from Cranborne Chase to Crete’ is at the Salisbury Museum until 7 May.