Human fascination with the dream world, combined with the transcendental vision of Renaissance artists, ensures that ‘The Renaissance and the Dream’, previously shown at Palazzo Pitti in Florence and now open at the Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, is nothing short of miraculous.

An overwhelming collection of paintings, drawings, engravings, sculpture and texts leads the visitor through different states of reality; from sleep, to the world of dreams, to the dawn of a new day.

Renaissance artists, imbued with belief in the potential of man and determined not only to emulate but surpass their classical forefathers, saw the representation of dreams as a chance to prove their talent, their superiority. To try to depict that which cannot be depicted, was to transgress the limits of art. The results of such a challenge were revolutionary.

The exhibition opens with ‘the night’. The first room, dedicated to the depiction of sleep, plunges you into silent darkness. In stark contrast to the bright, noisy Parisian streets, it feels as if you have transcended the outside world, arriving in a different reality.

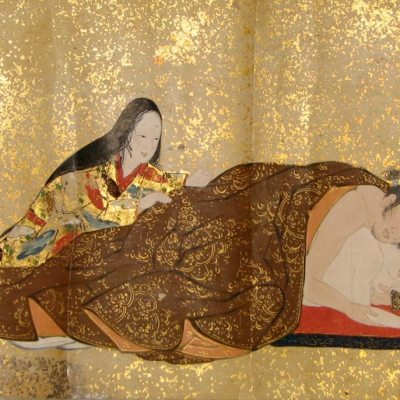

The majority of works in this room have been inspired by the iconic Renaissance image of the night – Michelangelo’s sculpture for the tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici in Florence (1530–34). A particularly striking interpretation is that of Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio (1553–55). He preserves the iconic position of the slumberous female nude. Her strong right arm holds up her head as she rests one elbow on her thigh, her fleshy stomach in folds as she curls into a position of rest. A Renaissance beauty, she is depicted against the dark and threatening background of the night.

For Renaissance thinkers sleep was a time in which the soul could free itself from its corporeal bondage and rise to a higher, often prophetic state. Renaissance philosopher Marsilio Ficino referred to this as ‘the vacancy of the soul’ and it is on this transcendental experience that the exhibition is hinged.

Visitors follow the soul into the realm of dreams – what awaits is a myriad of visions. One marvel of the exhibition is Raphael’s The Vision of a Knight (c. 1504), which depicts a young knight’s dream in which he is forced to chose between two fair maidens, one representing virtue and the other pleasure. It is a moral allegory, hinging on the dangers of lust and temptation.

Dreaming as a chance to reflect on sin is a recurring theme. The potency of conscience seems to follow the soul on its journey to a higher realm. This can be seen in The Vision of Tondal, attributed to the School of Hieronymus Bosch. Tondal, the protagonist of Marcus of Cashel’s illuminated manuscript, dreams that he experiences the punishments of sinners and the rewards of the good, as presented in the Bible. The painting asserts that punishment and reward are always in measure with the actions performed, an allusion itself to Dante’s idea of the Contrapasso.

One of the less known and less grandiose works is the anonymous Memento Mori on loan from The British Museum. It depicts Death asleep, leaning awkwardly on a sphere representing the world. It gives the impression that Death could at any moment wake up to fulfil his morbid role. It is Death who sleeps here, but the drawing serves as a sharp reminder that even in the dream world Death is present, and that in many ways being asleep is close to dying.

The exhibition concludes logically with ‘dawn and the awakening’. If sleep is close to death then awakening is close to resurrection. A highlight here is Battista Dossi’s The Morning: Aurora with Horses of Apollo, which represents the excitement and perhaps relief of the new day.

As you return to the bustle of modern Paris, the exhibition itself seems dreamlike, removed from the real world. An intellectual and spiritual journey, ‘Renaissance and the Dream’ should not be missed by anyone.

‘The Renaissance and Dream’ is at the Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, until 26 January 2014.