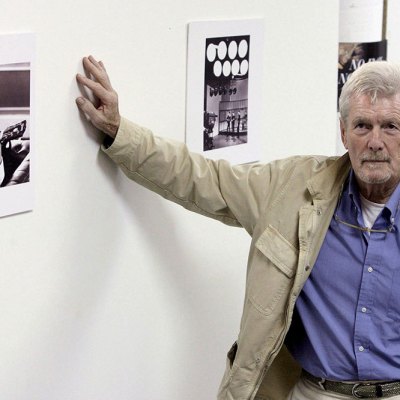

For his solo show at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1966, Ed van der Elsken (1925–1990) covered every inch of the floors and walls in his photographs and had his visitors walk over a larger-than-life printout of a naked woman’s back in order to enter the exhibition. The event quickly evolved into a kind of happening, with young people lining up to see ‘Ed’s’ work. Like his best-known photo-book Sweet Life, a visual record of his 13-month-long world tour published the same year, the show burst at the seams with Van der Elsken’s boundless, domineering energy.

Over the course of his 40-year career, Van der Elsken produced an estimated 100,000 photographs by roaming the streets of the world with his camera and, as he put it, ‘collecting my kind of people’. He likened his strategy to a hunt, and he was always on the prowl: ‘My ideal would have been to have a tiny camera built inside my head with a lens sticking out and recording “artistically” twenty-four hours a day,’ he wrote in 1986. He not only exposed the vulnerabilities of his subjects, but also his own: the Dutch public watched his second wife, the photographer Gerda van der Veen, give birth in the television documentary Welkom in het leven, lieve kleine (Welcome to the World, Little One) (1963), and watched him die of prostate cancer in his final film, Bye (1990). By the end of his life he had made some 50 films and 22 photo-books, and it is the work in his photo-books that has formed the bulwark of his legacy as one of the Netherlands’ most well-known photographers.

Schoolboys in uniform/Man carrying his daughter on his back, Osaka (1960), from the design mock-up for Sweet Life (published 1966), Ed van der Elsken. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. © Ed van der Elsken

The current exhibition comes one year after the Rijksmuseum and Nederlands Fotomuseum’s joint acquisition of Van der Elsken’s artistic estate, kept and maintained since his death by his third wife and widow, Anneke Hillhorst. ‘Ed van der Elsken: Crazy World’ (after the original title for Sweet Life) trains its focus on the working practice that makes the narratives in his photo-books so compelling – and so unmistakably his. Displayed across two rooms are clusters of individual black-and-white prints, primarily from the 1950s and ’60s, that take a variety of approaches to the same subject, demonstrating Van der Elsken’s search for the perfect shot.

Different crops, as well as variations in the quantity of black within compositions, account for dramatic shifts in focal point and atmosphere across images. A selection of photographs of the audience at a Lionel Hampton Big Band concert included in the 1959 photo-book Jazz shows how Van der Elsken alternated his focus between a euphoric fan and a blank-faced policeman, trying to find the right balance between his two protagonists. A similar selection process can be seen in a series of prints recording Elizabeth II and Prince Philip’s state visit to The Hague in 1958. There is an entire contact sheet of the crowded ceremony at the Ridderzaal on display, on which Van der Elsken has circled positives of Pieter Gerbrandy and Louis Beel, the then former and current prime ministers of the Netherlands. In the final prints he has zeroed in on their faces exclusively, and they appear to emerge from a sea of black with no one surrounding them.

The state visit of Queen Elizabeth of Great Britain to the Netherlands (1958), Ed van der Elsken. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. © Ed van der Elsken

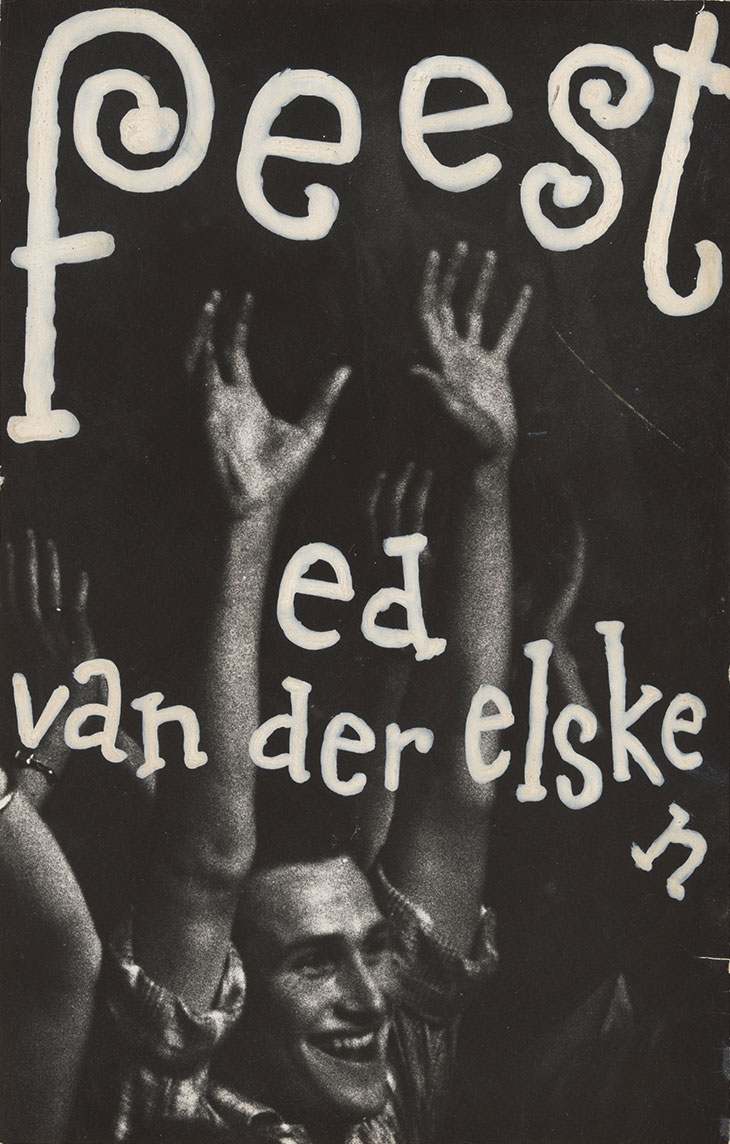

These prints appear side by side in the biggest surprise of the purchased estate: a hitherto unknown, pocket-sized photo-book titled Feest (Party), which has been recreated by Rijksmuseum curators Hans Rooseboom and Mattie Boom and published for the first time to accompany the exhibition. Plans for the cover design and layout had been preserved by the artist’s widow at his home in Edam, and were made by Van der Elsken at the same time he was working on Sweet Life. Why it was left unpublished isn’t clear, and there are no records of the project being discussed with publishing houses or fellow photographers.

Feest was originally intended by Van der Elsken to have 64 pages but in its current form it has more than double that. The pocketbook – then a popular publishing format – features all prints found in the estate that the curators could identify as originally designated for the project by Van der Elsken himself. The photographs were taken over the course of the 1950s, with a few trickling into the 1960s. Some shots – including two images of a military parade in Paris on Bastille day, presented stacked across a double-page spread – were taken abroad, but the majority of the events photographed took place in the Netherlands. Feest documents ceremony and celebration at all strata of Dutch society: from Elizabeth II’s state visit to parties at the studio of CoBrA artist Lucebert and the publishing house of Flemish writer Hugo Claus, to liberation commemorations and May Day parades, fairs in Amsterdam and Volendam, and Carnival celebrations in Maastricht.

Cover design for Feest, featuring a photograph of the audience at a Louis Armstrong and His All Stars concert in Blokker, the Netherlands, 1959. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. © Ed van der Elsken

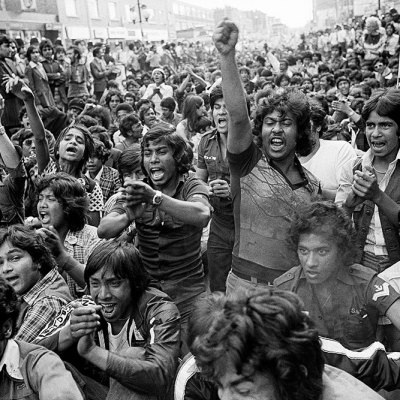

As we walked through the exhibition, Rooseboom pointed out a series of prints from Sweet Life, showing Civil Rights protests outside a Woolworth store in New York. A wave of protests and sit-ins at branches of the department store took place in 1960 after four African American college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, sat down at a Woolworth lunch counter and refused to leave when denied service. ‘Sweet Life is best known for its beautiful layout,’ Rooseboom said. ‘It’s cinematographic, and very dynamic. But it has real historical significance as well. Van der Elsken wanted to show us – and the audience back then – what was going on in the world. And that’s often overlooked.’

Just as he captured burgeoning movements abroad, in Feest Van der Elsken documented his own country’s post-war transformation. The community and freedom of spirit captured by the book’s pictures evoke a special moment of possibility in Dutch history. Ed van der Elsken had to wait six years to find a publisher for Sweet Life; it is perhaps fortuitous for us now, as we sit out the rest of this pandemic still, separated and alone, that we had to wait 60 years for Feest.

‘Ed van der Elsken: Crazy World’ is at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, until 10 January 2021.