Ben Uri is celebrating its centenary this year. The organisation, which began life in 1915 as a Jewish artists’ society in the East End of London, has since its inception been an indefatigable champion of British and European artists of Jewish descent, giving rise to many important exhibitions and publications in spite of historically limited resources. These days, it is an accredited museum with a distinctive collection that numbers some 1,300 works.

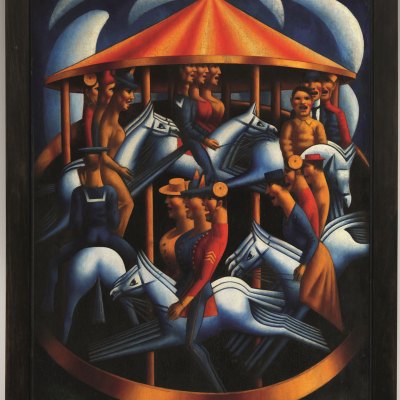

Highlights are currently on display in ‘Out of Chaos; Ben Uri: 100 Years in London’ (until 13 December) at Somerset House. In artistic terms, this is a rewarding exhibition, with very good things by David Bomberg, Mark Gertler, Leon Kossoff, and others. But what makes it truly compelling is the institutional story it tells, of how the lives of artists have intertwined with the society established to promote their output, and of the successes and strains of a small, independent institution. Its perseverance against the odds is encapsulated here by Gertler’s masterpiece, Merry-Go-Round, which was sold by Ben Uri in 1984 to head off a funding crisis and appears in the exhibition on loan from the Tate.

Ben Uri’s triumphs are epitomised by the current exhibition at its temporary exhibition space in St John’s Wood, in northwest London. ‘Rothenstein’s Relevance: Sir William Rothenstein and his Circle’ (until 17 January 2016), a collaboration with Bradford Museums and Galleries, is the type of judicious display that the museum puts on so well. It offers a long- overdue survey of a painter whose work emerged from the fashionable innovations of the fin de siècle and whose preference for humble subjects and commitment as an Official War Artist made him such an influential figure for modern British artists including Gertler, Eric Kennington, and Barnett Freedman. Rothenstein, like so many of us in this mongrel nation, was both deeply drawn to his (German-Jewish) cultural heritage and practically estranged from it; the exhibition contrasts his earnest scrutiny of Jewish ritual in Whitechapel with his preference for modern subjects in domestic scenes and portraiture.

Visiting the exhibition in St John’s Wood, it is clear just how far this location hampers Ben Uri. There is very restricted gallery space, with no room to display works from the permanent collection, and – by touristic standards at least – it is on the periphery of central London. While such things may invest the place with a ‘hidden jewel’ quality, accidental seclusion is not much use when it comes to operating costs. From this perspective, the centenary display at Somerset House is not only a serious historical overview but also, in the nicest possible sense, a candid PR exercise: it aims to gather support for the proposed relocation of the museum, and the extension of its remit.

Ben Uri is searching for a central London home, in which it will relaunch as a museum of ‘art, identity and migration’. This will enable it to implement fully its ecumenical aspiration of championing the art and experience not only of Jewish, but of all émigré communities. There is currently nothing of this sort in London, save the ‘Museum of Immigration and Diversity’, which is housed in the evocative Victorian synagogue building at 19 Princelet Street, Spitalfields, but is sadly open to the public on only a handful of days each year.

It is easy to have reservations about the project. Scaling up is a risky strategy for an institution that has sometimes struggled to make ends meet. And one wonders how this idiosyncratic collection will hold water in lofty premises, or when pushed to illustrate grand abstractions of ‘identity’ and ‘migration’. The new museum will require sustained collaboration between different communities, and all kinds of good will and generosity. But my heart wishes Ben Uri every success. As the UK government tightens its blinkers on the subject of refugees, and Europe faces its worst refugee crisis since the Second World War, there could hardly be a more prescient time to celebrate émigré art in this country – and all that we can learn from it about assimilation and remembrance.