From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

At first glance, ‘Paolozzi at 100’ might seem little more than a dutiful gesture on the centenary of a key figure in the history of the National Galleries of Scotland. It was a bequest from the sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi which, 30 years ago, endowed the galleries with an important 20th-century collection and helped to secure the National Lottery money that founded the Dean Gallery (now Modern Two). Even the title of the exhibition suggests an echo or aftershock of that millennial big bang, which culminated in ‘Paolozzi at 80’ in 2004. Yet this free exhibition wisely avoids restaging that triumphal march through decades and phases. While some artworks might be familiar to repeat visitors with long memories, this centenary show tells its own story, taking a particular interest in Paolozzi’s collaborations and connections with other artists, theorists, technicians, craftspeople and engineers.

Paolozzi is on home ground here: he was born in Edinburgh and, though his working life was spent mostly outwith Scotland, the city has fully embraced the association. (If you don’t fancy a post-exhibition snack at the gallery cafe, Paolozzi’s Kitchen, you can stroll over to Paolozzi Restaurant & Bar in the Old Town for a pizza washed down with ‘Paolozzi’ craft lager.) A full-scale reconstruction of the artist’s Chelsea studio has long been a permanent fixture of Modern Two, as has his hulking 24-foot-high Vulcan (1999) in the cafe and the more restrained statue of Isaac Newton (Master of the Universe, 1989) that stands in the curtilage. Along the central corridor run vitrines housing the artist’s array of trinkets and curios, from parking meter mechanisms to plastic models of the cyborg from The Terminator. All of this helps to fortify and contextualise the collection of works arranged across the exhibition’s three rooms, which show some of the results of Paolozzi’s dynamic, experimental process.

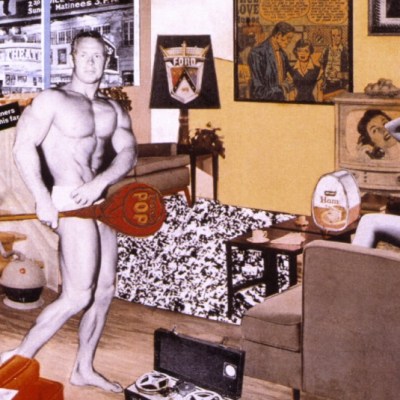

Collage (1953), Eduardo Paolozzi. © The Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS Artimage 2023

‘Paolozzi at 100’ offers samples rather than a synthesis, relying – as the artist himself often did – on the method of collage to bring out unexpected juxtapositions and surprising patterns. One room deals largely with the early work in sculpture and on a series of 1950s ‘design exercises’ in ink and gouache, made while Paolozzi was working as a tutor at the Central School of Arts and Crafts and studying screenprinting techniques with the Austrian art theorist and refugee Anton Ehrenzweig. Off to one side sits the reconstructed studio with its gallimaufry of plaster busts, musical instruments, action figures, aeroplane propellers and other junk shop finds. Three minatory bronzes of the 1950s – Krokodil, His Majesty the Wheel and Saint Sebastian I – stand like robot sentries in front of a casually draped swatch of teal screenprinted cloth. The sculptures, constructed out of forms cast from wax mouldings stamped with scraps of metal, cogs and bolts, suggest mangled artefacts excavated from some machine-age disaster. By contrast, the square of couthy ‘Portobello’ fabric – a creation of Hammer Prints, the textile company Paolozzi co-founded in 1954 with the artist Nigel Henderson – teems with Paolozzi’s sketches of bric-a-brac found in London’s antique markets. Both the sculpture and the fabric display the artist’s enduring fascination with the conjunction of technological and organic forms. Yet where the former belongs to the apocalyptic post-war style that Herbert Read christened the ‘geometry of fear’, the latter evokes the rather more optimistic (and lucrative) world of mid-century interior design.

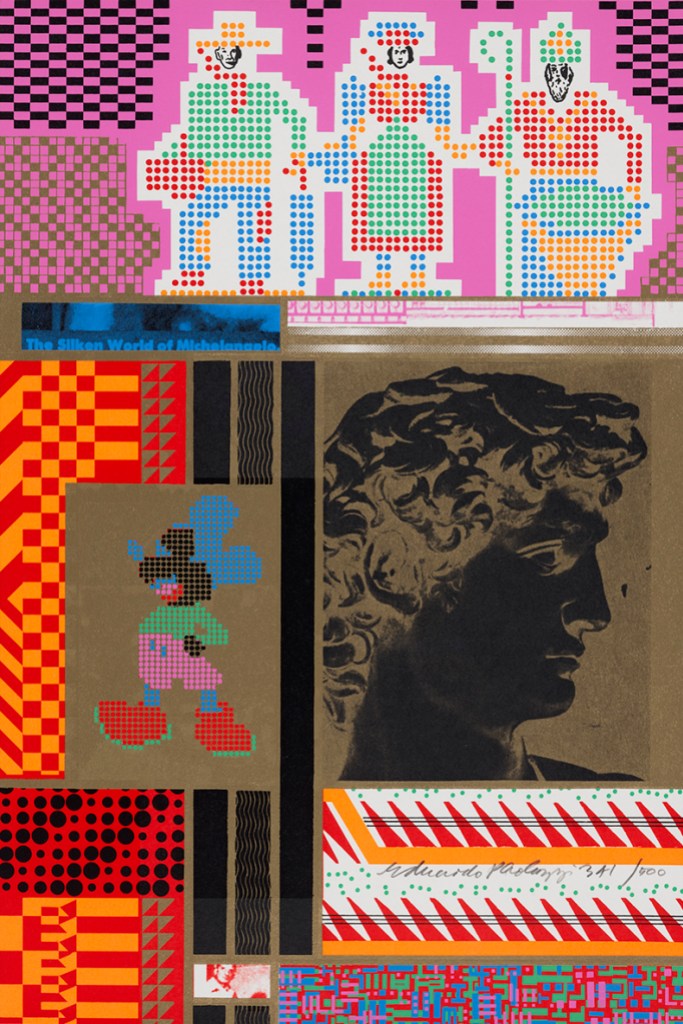

Paolozzi’s fusion of modernism and the commodity fetish continues in a second room, where a selection of commercial collaborations – textiles for Lanvin; high-end ceramics for Wedgwood – share space with samples from his dazzling screenprint portfolios of the 1960s and ’70s, including the eye-popping, space-age Moonstrips Empire News (1967) and Calcium Light Night (1974–76), a homage to the composer Charles Ives. More prominent still are three prints from the earlier series As Is When (1964–65), which takes as its theme the life and work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. A short film zooms in on the Lanvin collaboration, showing off the resulting Paolozzi-print dress, while a neighbouring wall is hung with a tapestry including the pixelated yet unmistakeable image of Mickey Mouse – a test piece for the larger tapestry Paolozzi designed in 1967 for the opening of the renovated Whitworth Gallery in Manchester.

The Silken Worlds of Michelangelo from the ‘Moonstrips Empire News’ series (1974–76), Eduardo Paolozzi. National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

These juxtapositions neatly demonstrate the artist’s technical skill as well as his remarkable range, across not only different media but also various domains of intellectual and popular culture that, for him, were never really distinct. As this cross-section of his printed works aptly shows, Paolozzi was a genuinely international artist, fusing the iconographic traditions and registers of mid-century Europe and the United States. This is art as a creative response to a world that includes both philosophy and fashion, commercial activity and abstract thought, Wittgenstein and Walt Disney.

A final set of exhibits in the Gabrielle Keiller Library (named for the artist’s friend, patron and fellow benefactor) concentrates on public commissions, including monumental sculptures such as the 12-foot-high Newton after Blake, who sits, hunched over his compasses, in the courtyard of the British Library, as well as the mosaics Paolozzi designed for Tottenham Court Road tube station. These exhibits offer a glimpse of the numerous practical and logistical challenges faced by sculptors working at scale and of Paolozzi’s management of his grand designs from conception to installation. One exhibition text quotes the art historian Frank Whitford’s approving description of Paolozzi’s studio as ‘more like an operations centre and information retrieval system than an artist’s workshop’.

Eduardo Paolozzi, 1999 (2003), Debra Hurford Brown. National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

Paolozzi has frequently been compared with Warhol as a progenitor of Pop art, hailed as a post-war European visionary and associated with the Independent Group and its dislike of modernist snootiness. With its focus on transactions between art and commerce, private experimentation and public commission, ‘Paolozzi at 100’ left me with a somewhat different impression of the artist – as a pioneer of the applied arts across several media, an inheritor of the Arts and Crafts movement and an impresario with a talent for forging working relationships as well as titanic bronzes.

‘Paolozzi at 100’ is at Modern Two, Edinburgh, until 27 April.

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.