On the first day of February, President Trump announced that he was closing the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., for two years. This closure, Trump said, would allow the ‘construction, revitalisation, and complete rebuilding’ of the landmark. ‘Complete rebuilding’ must be a bit of Trumpian hyperbole, surely? Possibly, but given the recent, unexpected demolition of the entire East Wing of the White House to make way for a ballroom, it might be the plain truth. The Kennedy Center may not be as close to the medulla oblongata of American power as the East Wing, but it is part of the same nervous system. And the East Wing made a virtue of being inconspicuous (a quality that will be much missed when the ballroom takes shape), while the Kennedy Center is a showpiece, a conspicuous statement of national confidence and pride. Which makes it rather strange that so few people today would know the name of its architect, Edward Durell Stone, or the details of his fascinating career.

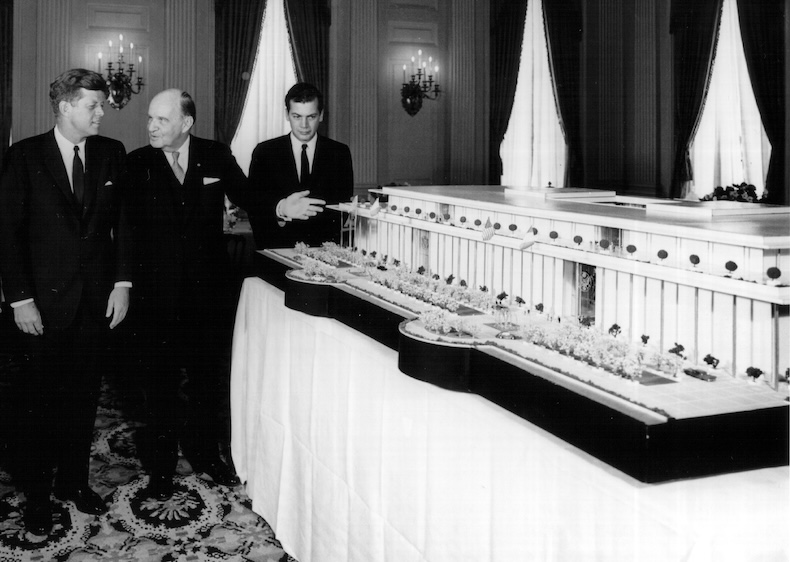

When the Kennedy Center was completed in 1962, Stone was one of the most prominent and in-demand architects in the United States. Near the start of his career he was part of the large team of architects that designed the art deco Rockefeller Center in New York City. Shortly afterwards Stone was commissioned, with Philip L. Goodwin, to design the Museum of Modern Art, completed in 1939. This was executed in impeccable International Style modernism, still fairly startling at the time. But after the Second World War, Stone struck on a formula for softening the rather forbidding strictures of early modernism without jettisoning its monumental qualities.

The exemplar of this was the US embassy in New Delhi, completed in 1959. This is a sculptural and rigidly geometric building, raised on a podium like a temple, and might easily have been oppressive. But Stone takes the edge off by perforating the walls, making them almost delicate, and sheltering the building under wide projecting eaves supported by slender pilotis. An aftertaste of Jeffersonian new-world classicism can be detected, with the faint echo of the suburban porch. Exactly the same approach was taken at Stone’s US pavilion at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels, curved into a cylinder, with an even lighter veil. The architectural historian Vincent Scully, writing at the end of the 1960s, is scornful about this tactic, calling it ‘literally, superficial’, an act of mere packaging, in which a ‘fundamentally Miesian’ volume is given a surface ‘as crumpled and laced up as the trade can afford’. (Lurking just off the edge of the page was the term ‘decorated shed’.)

Nevertheless, this was the packaging the United States used to ship itself around the world – it was, for a time, pretty much the official national architecture, an aesthetic the architecture critic Herbert Muschamp much later described as ‘First Lady architecture’, a soft-power design language ‘to complement the harsh realities of cold-war geopolitics’. (For all his immense success with clients, Stone doesn’t do well with the critics, which is often the way.) The Trump administration has sought to portray modernist architecture as a sinister deviation from a main stream of American greatness, but the work of Edward Durell Stone is the closest architectural translation of American power and self-assurance at its zenith.

At the Kennedy Center, the overhanging eaves and slender gold pilotis are reiterated, although the perforation is not, rather to its detriment. (‘Repellent’ – Scully.) It’s a Cold War idiom for a Cold War building, better understood in a global context than as a contribution to the domestic arts. It owed its existence to a cultural arms race of sorts, in which the United States and USSR were eagerly watching what the other was doing – indeed Scully detects the influence of Stone in the entries to the 1959 competition for the Palace of the Congresses in Moscow. It probably won’t endear it to Trump but the Kennedy Center is an anti-communist building that is also of a type the Communists understood well. It is, in a way, an American Palast der Republik, and it may now be facing the same fate as that unhappy East Berlin landmark, which was torn down and replaced with a baroque pastiche in an act of historical vengeance. History, including architectural history, sometimes rhymes.

There’s a strange appendix to the Edward Durell Stone story. In 1964, he committed an extraordinary act of apostasy in his design for a private art gallery at Two Columbus Circle in New York. Modernist orthodoxy was flouted in favour of overt decoration and historical reference – reference, moreover, not to classicism but to the more excessive end of Mediterranean gothic. In the New York Times Ada Louise Huxtable famously described it as ‘a die-cut Venetian palazzo on lollipops’. It was a wilful oddity, an act of proto-postmodernism. Unsuccessful as a private gallery, it stumbled from use to use for years and in the 2000s it was given a miserably uninspired makeover by Brad Cloepfil. Trump – who owned an adjacent site – wanted it torn down.