From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

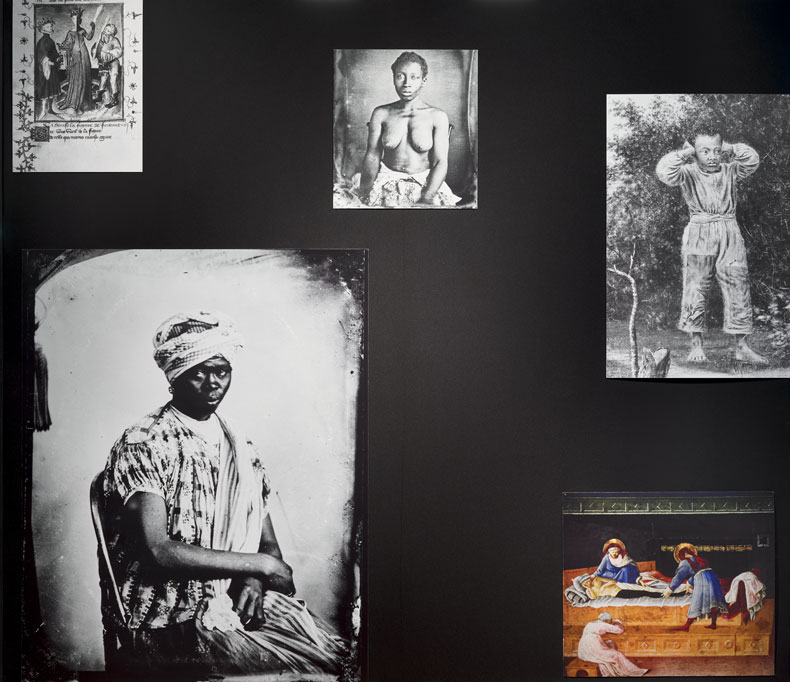

Pause for a moment just inside Edward George’s exhibition ‘Black Atlas’ at the Warburg Institute and your eyes will register two bodies with a near-identical posture. Both are photographs of artworks, the first a painting by Kees van Dongen from 1914 of Jack Johnson, boxing’s first Black heavyweight champion and the son of freed slaves; the second an ethnographic daguerreotype of an unidentified man with his back to the camera. I suppose you could put the repeat down to coincidence, but a few steps in, the same shape appears in a picture of a lynching, and a feeling of curiosity – even uneasiness – begins.

The whole show – three multi-image triptychs and a film piece – is alive with these sorts of echoes. Whichever of the 50 or so pictures on the wall your eyes happen to alight on, something else will jostle for attention in a corner of your vision or your memory, and the opportunity to reflect on possible harmonies or tensions is intentionally provocative.

Commissioned by the Warburg, the exhibition is a response to the Image of the Black archive, an encyclopaedic collection of 30,000 reference photographs that the Institute acquired in 1999. Established by the French-American collectors Dominique and Jean de Menil at the height of the Civil Rights movement in the US, it documents the presence of people of African heritage in Western art from antiquity to the middle of the 20th century, and it’s never been on public display in Britain before.

It’s an extraordinary inheritance, exhaustive in scope and rippling with eccentricities, though not without its snags. Not least that any insight such a gathering of images might claim to provide into changing perceptions of Africa and ideas about race and Blackness over the past 5,000 years is filtered through Western art and Western eyes. ‘The caveat is “nothing is by you”,’ said George, who was installing the exhibition when I visited. ‘It’s anti-racist, but doesn’t absolve itself.’

George, a multi-disciplinary artist and a founding member of the Black Audio Film Collective, has long been preoccupied with ideas about history, memory, race and nation. Here, his response to the Image of the Black archive amounts to a form of visual exegesis that conveys both its stretch and – critically – its strangeness, but also his own process of discovery: a year sifting through photocopies of pictures on his hands and knees in the Warburg’s basement, keeping to one side anything that confused or surprised him. The startling number of images depicting a medieval miracle in which a white man’s diseased leg was replaced with one cut from a deceased black man, for instance. Or so legend has it.

‘Black Atlas’ takes its name from the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, a radical visual experiment by Warburg Library founder Aby Warburg, a German art historian and cultural theorist, for which he pinned clusters of images (postcards, diagrams, newspaper clippings, parts of paintings and so on) to black hessian-covered panels in order to map connections between cultural artefacts throughout history. Named for Mnemosyne, the Greek goddess of memory and mother of the nine muses, his project upended the tradition of considering pictures only in terms of their adherence to an academic style, and is now hailed as an artwork in itself.

In the exhibition, George replicates those black boards, arranging them as three triptychs that call to mind the folding ‘winged’ altarpieces that proliferated in churches throughout northern Europe during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Its subtle nod to the canon of European art must be intentional – there are others all over the show, such as a panorama curtain that inverts one of Botticelli’s illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Each picture goes against these familiar historical currents, or sometimes with them.

Of course, by virtue of its setting, the exhibition must necessarily engage with the traditions of art history, whether good or ill. The Warburg is home, after all, not only to the library and papers of a scholar who dedicated his life to understanding the power of the image, but also the archive of its longest-serving director, E.H. Gombrich, whose book The Story of Art has been required reading for art historians since its publication in 1950. You even pass a vitrine presenting its various covers on your way in.

Crowning ‘Black Atlas’ is an hour-long film: a sequence of pictures narrated in elliptical but poetic fashion by George with a sound-collage score by artists Crystabel Riley and Seymour Wright (George’s fellow band members in the group X-Ray Hex Tet). Its shifting cast of saints, magi, warriors, evocations of ‘exotic foreigners’, ladies’ maids and the enslaved roams across centuries of fantasy, fear and fascination with Blackness, with a lilt and insistence that is intensely affecting.

What’s on the black boards then? Lots. A painting by Degas, a ‘smoking negro’ clock, a 16th-century manuscript, cutlery with carved handles, Queen Victoria’s seal for the island of Jamaica, a curtain for a moving panorama of the Mississippi Valley. The way they are arranged in their clusters feels sparse but taut, and invigoratingly unpredictable. We are nudged from oddity to oddity, rather than held by the scruff of the neck, so that overall the show feels less like censure than an invitation.

Just as Warburg was perpetually tinkering with his Bilderatlas, George will change the constellations of images over the run of the exhibition. He has also chosen to present them without captions, but an optional handout is available. Though at first it makes you feel at sea, resist the lure of that familiar frame if you can, because once set loose from hobbling detail and context, the images perform differently, their emotional weight rising beautifully to the fore.

‘Edward George: Black Atlas’ is at the Warburg Institute, London, until 17 January 2026.

From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.