From the October 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

On the great televised state occasions you cannot see Methodist Central Hall because the cameras pointing towards Westminster Abbey are placed on its roof. But from the ground you cannot miss it. The innovative constructional methods, sophisticated section and layout of this enormous Edwardian building were the work of H.V. Lanchester, but its unusual French-Viennese baroque facades, its luscious staircase, unequalled in London, and its rich sculptural detail were created by his brilliant young partner Edwin Rickards (1872–1920). His almost lifelong friend, the novelist Arnold Bennett, said at his death that ‘the two most interesting, provocative, and stimulating men I have yet encountered are H.G. Wells and E.A. Rickards’. Tellingly, all three came from families with connections to drapery; the weaving, cutting and folding of cloth to the highest standards of late Victorian England is an analogy that suits all of them.

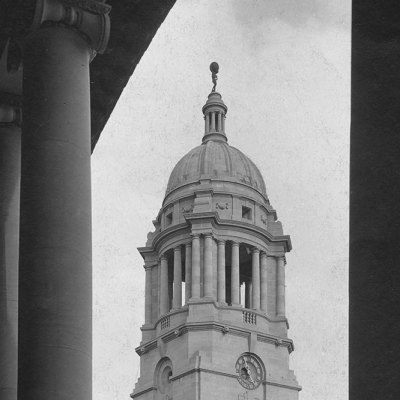

Rickards was the son of a draper and grew up in the inner suburbs of west London. He was repeatedly mistaken by snobbish contemporaries for a cockney, as if he were a shop assistant posing as a professional: his younger colleague Charles Reilly, later a much-revered teacher of architecture, made exactly this comparison. He worked for several architects in his youth, jobbing in more than one office at a time; picked up a bit, probably not much, from classes at the Royal Academy and the Architectural Association; went into a trial partnership with Lanchester and James Stewart as a vehicle for entering competitions, and at the age of 25 designed with them the winning entry for what is now Cardiff City Hall. This building was, and remains, a baroque palace of astonishing splendour quite unlike any other municipal structure in Britain.

Arthur Beresford Pite, one of several serial competition losers who were jealous of Rickards, wrote spitefully in an obituary that his rival’s success was due to ‘breadth in elevational treatment, supported and gingered by picturesque features and sculptured sweetness’. Rickards was indeed a superb draughtsman and also a talented illustrator and caricaturist, but the submitted drawings for Cardiff give no sense of the lushness of the building’s eventual form. They are dry and concise, and what is likely to have attracted the support of the assessor Alfred Waterhouse was its rational layout by Lanchester, the precursor to the many modern institutional plans he was yet to design for universities and hospitals.

Pite was no doubt referring to Rickards’ best-known competition drawing, for the partnership’s proposal in 1907 for London County Hall, in which a spectacular cascade of masonry tumbles down from a great tower into the Thames showering festoons, fruit, trophies and urns in all directions and at all levels. This design was not actually submitted and was published only after he and Lanchester had failed to make the shortlist. Inspired by the Central European baroque, and whatever he saw as he dragged himself around the Mediterranean after suffering a nervous breakdown in his early 20s, the facades and interiors of Rickards’ buildings are drawn from a fantastical vision of architecture otherwise not realised in Britain, maybe most resembling some massive compilation of the most outré Italian funerary monuments.

The upper landing of Deptford Town Hall (now part of Goldsmiths University), designed by Henry Vaughan Lanchester (1863–1953) and Edwin Rickards (1872–1920) and completed in 1905. Photo: Robin Forster

Rickards designed five substantial executed buildings with Lanchester (Stewart retired in 1902 and died two years later), nearly all of which are intact today; the nave of their Third Church of Christ, Scientist, in Mayfair, has been demolished, but that was the least interesting part of it. The two municipal halls are in perfect condition and the Hull School of Art, now the Northern Academy of Performing Arts, an exquisite building with a masterful stair hall, even retains the original coat hooks and lavatory cubicle doors.

Rickards had a single architectural theory, repeated in his few published talks, which was that sculpture should be integrated into the surfaces of a building: a rigid statue on a plinth reminded him, he told the Architectural Association, of the school dunce being made to stand on a stool in the centre of the classroom. There was also an appeal to ecstasy, in references he makes to the contemporary Symbolist artists Charles Sims and Gaston La Touche, and to a fragment of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855) that hints at facades of austere modern buildings hiding passionate interiors. In fact, the way to see Rickards is as a rare British Symbolist. His buildings are studded with motifs of the contemporary European avant-garde: stylised roses; curious bracelet-like chandeliers; a row of figures forming a frieze, as along the street front of the upper floor of the partnership’s Deptford Town Hall of 1902–05. Within its staircase hall the plaster artist George Bankart created to Rickards’ design an astonishing rococo relief that frames the entrance to its council chamber, possibly derived from that at the Upper Belvedere in Vienna: there are mermaids and scallop shells, elements that Rickards used elsewhere, alongside the chains, anchors and lanterns depicted in the hall’s ironwork. Rickards and Lanchester drew on the best artists of the new sculpture – notably Henry Poole and H.C. Fehr – but drawings show that it was Rickards who worked out the details.

Some were appalled by Rickards; a few delighted. The unconventionality of his architecture matched the unconventionality of his life, much of it spent in a demi-monde of showgirls and late-night Soho theatre suppers. This was someone whose personality never changed throughout his relatively short career of scarcely 25 years; nor did his dreams and aspirations. As with other architects of buildings that appear to be singular, he is not easily categorisable and doesn’t fit into the lists that architectural historians make – not even as a freak, like Simon Rodia or Friedrich Hundertwasser, who regularly make it into mainstream surveys, or some of the more absurd Jugendstilers. Here was an Edwardian master who was very much his own man.

From the October 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.