From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In a decade or two of working on architecture magazines, I dealt with publicists every day. Often maligned as obstructive, they were generally essential, the people you could get on the phone, the people who understood what kind of images you needed, how much time and access was desirable for an interview, and what a deadline was. But they weren’t working for us, the magazines. They were working for architects, shepherding their buildings into the light, building up their reputations. Eva Hagberg’s When Eero Met His Match is an intriguing book about the formative years of this profession, the middle of the 20th century.

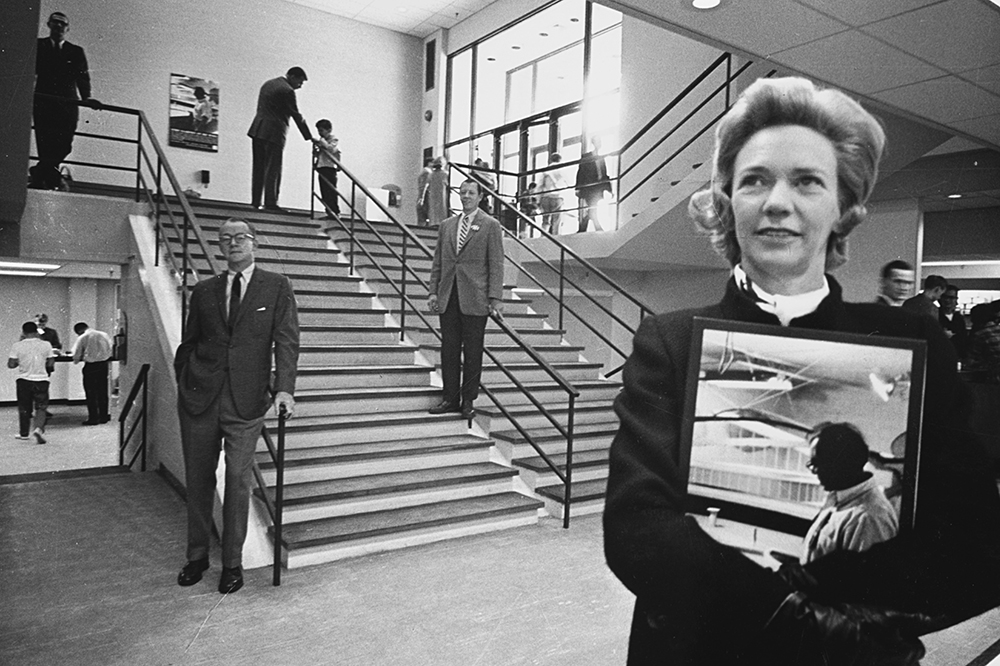

The Eero of the title is the Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen, today remembered as a genius of mid-century dash thanks to buildings such as the TWA terminal at JFK airport. The ‘match’ is Aline Louchheim Saarinen, Eero’s second wife, who ran the public-facing side of his office for the last years of his life. This relationship was a remarkable intermingling of the personal and the professional, and Hagberg’s aim is to pick out Louchheim’s influence on the perception of Saarinen’s great final works, and possibly over the architecture itself.

TWA Terminal now JFK Airport in New York, designed by Eero Saarinen and built in 1959–62. Photo: © Ezra Stoller/Esto

This task requires a very close reading of correspondence between Aline and Eero and between the Saarinen office and editors such as Douglas Haskell of Architectural Forum. Meaning and nuance are frisked from phatic turns of phrase such as ‘I guess’. There is a great deal of this kind of thing: ‘[Architectural Record editor James] Hornbeck, by calling back to the last time he saw Louchheim, was reconstituting their personal relationship before moving to this professional request – and it was presented as a request – thereby exhibiting her power.’ Hagberg teases out Louchheim’s gentle manipulations of the press and the evolution of the techniques of architectural publicity – mostly, then and now, a question of who gets what images when.

Surely, you will think, this is an astoundingly niche subject, of interest to a handful of people. But the book is genuinely strange and beguiling. Much of When Eero Met His Match began as a thesis, the natural home of this kind of forensic effort. Hagberg, at the time she embarked on her Saarinen research, was an architecture writer who had started to take on work as an architectural publicist, eventually building up an extensive and lucrative business. Her discovery of a talent for publiclity led to a mild infatuation with Louchheim.

Louchheim and Saarinen began their relationship in 1953, after Aline – a noted art critic – interviewed Eero for the New York Times. Something of a type-A personality, she pursued him with astonishing dedication, both professionally and romantically, simultaneously auditioning as both wife and publicist. Her pitch was that she would be a devoted manager of his life and reputation, freeing him to think of nothing but architecture. This was exactly what Eero, then ending his unhappy marriage to the sculptor Lilian Swann, wanted – an astonishingly frank letter to his psychologist lays out the very high demands he made of a wife. Those were demands Aline relished meeting, however, and the alternation in her letters between blinking submissive innocence and steely determination makes it clear that no one was being naively exploited.

Cover of When Eero Met His Match: Aline Louchheim Saarinen and the Making of an Architect by Eva Hagberg

Once married, and running the office, Louchheim changed how Saarinen’s work was perceived. He used state-of-the-art engineering to create dramatic, sculptural forms, but descriptions of those buildings could be drily technical. Louchheim inserted poetry into the way the press talked about them, as well as personal touches about the ways Eero worked (toying with his breakfast grapefruit, sketching on ruled yellow pads). In the process, she helped shape architecture criticism as we know it.

All this was done with the publicist’s major tool: talk. Aline talked to Eero, helping him express his ideas, and then she talked to the press. Hagberg sees this as Louchheim ‘gesturing towards the importance of a contiguous narrative mode in the production of architecture’. In other words, more or less, talking about architecture was part of making architecture.

The publicist has to work between the ego of their employer, the architect, and the egos of the journalists and editors who govern the press – delicate territory, full of potentially wounded feelings. Hagberg’s experience of the field brings her account of Louchheim alive in a series of short autobiographical essays interspersed between chapters, and in insights woven throughout. ‘How many times had [a publicist] told me I was the perfect person for something? How many times had I totally believed it?’ Hagberg asks, having found herself using those honeyed words with a writer. ‘Except in my case, with this writer, I did believe it; just as I think, in many ways, the publicists who were pitching me did too.’

Even if they don’t involve marriage, the relationships between architect and publicist, and publicist and writer, are acutely personal. ‘I noticed that we were all women and that our clients were overwhelmingly men,’ Hagberg writes. ‘I also noticed the way in which I started to create a certain intimacy with my male clients, an intimacy that never crossed the line into the sexual, but that became nevertheless a form of the erotic.’

Louchheim and Saarinen’s relationship was tragically brief – he died of a brain tumour in 1961, aged 51, just as his career was exploding into worldwide fame. Aline turned to the posthumous management of his reputation. But in a way, Hagberg writes, that is what publicity is all about. ‘So many of my clients paid me not so that they would be published in the moment at hand but so that, in some future world, they would get the kind of clients that they thought they deserved.’

Hagberg gives the discreet and specialised world of the architectural publicist an aura of romance and intrigue. Though its task is confined, When Eero Met His Match is an expansive, candid, insightful and oddly sexy book. As a tribute to Louchheim, it is impressive; as a portrait of an overlooked profession, it is revealing, funny and moving.

From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.