This review of A Look at My Life by Eileen Agar (Thames & Hudson) appears in the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘My life is a collage, with time cutting and arranging the materials and laying them down, overlapping and contrasting, sometimes with the fresh shock of a surrealist painting.’ There are plenty of ‘fresh shocks’ in Eileen Agar’s autobiography A Look at My Life (1988), which has been republished (with colour illustrations) after too many years of being out of print. Written three years before Agar died at the age of 91, it is an engaging book, full of witty anecdotes and perceptive insights.

Born in 1899 in Argentina to British and American parents, Agar had a childhood of immense privilege. The family resettled in London in 1911 and, when she was old enough, evenings were spent dancing and avoiding attempts by her ‘lioness of a mother’ to match her to a Belgian prince or roaming marquis. She soon abandoned the existence to which her glamorous but conventional mother was attached. Yet early visual experiences had left their mark; lines of inspiration can be traced from her mother’s opulent hats to her own Surrealist take on headgear in the form of Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse (1936). In 1921 her parents allowed her to study fine art at the Slade under Henry Tonks. It was in these years that she began to strike out on her own, living in a small flat in Chelsea and shaving her hair back from her forehead (a trademark Slade-girl style of the time). Her first marriage, to fellow painter Robin Bartlett, was ‘an escapehatch’ which freed her from family ties.

Born in 1899 in Argentina to British and American parents, Agar had a childhood of immense privilege. The family resettled in London in 1911 and, when she was old enough, evenings were spent dancing and avoiding attempts by her ‘lioness of a mother’ to match her to a Belgian prince or roaming marquis. She soon abandoned the existence to which her glamorous but conventional mother was attached. Yet early visual experiences had left their mark; lines of inspiration can be traced from her mother’s opulent hats to her own Surrealist take on headgear in the form of Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse (1936). In 1921 her parents allowed her to study fine art at the Slade under Henry Tonks. It was in these years that she began to strike out on her own, living in a small flat in Chelsea and shaving her hair back from her forehead (a trademark Slade-girl style of the time). Her first marriage, to fellow painter Robin Bartlett, was ‘an escapehatch’ which freed her from family ties.

In 1926 she met the writer Joseph Bard – a handsome Hungarian with a ‘Roman rudder of a nose’, dazzling intellect and Byronic reputation. He was, she writes, ‘the warmth of my life for nearly sixty years’. Agar credits Bard with enabling her to ‘grow up’ and begin a new life, simultaneously gaining more selfconfidence and artistic maturity while breaking with representational painting. For many years the couple lived ‘car-less and careless’ in two London flats in the same block (a nod to convention as they were unmarried until 1940, when she proposed to him – the wedding took place on a leap day). According to Agar, neither side of the union was unsettled by the various liaisons of the other, although Bard eventually lost patience with her deep artistic and romantic attachment to the painter Paul Nash.

Agar never misses a beat. She seems to have befriended or made lovers of most of 20th-century Europe’s literary and artistic luminaries. In Rapallo, the poet Ezra Pound gives predictably Poundian advice on what she should aim for as a painter – ‘clarity, structure and vital energy’ – offering the axiom: ‘Don’t be a wobbly vagina, not that I think you are.’ In Paris she admires Brâncuși’s studio as the sculptor makes his birds quiver with a touch of the hand. She later comes to Dalí’s rescue when he starts suffocating while giving a speech encased in a metal diving costume. In the late ’30s, despite the threat of war, she enjoys sun-drenched holidays with Lee Miller, Dora Maar and Picasso in the South of France. Agar was wary of submitting to the artist’s magnetism; her account brings ‘Picasso the Master’ down to earth by mentioning trips to the shared loo. They both had a love of objets trouvés and his gift of a cork eventually became part of her collage The Object Lesson (1940).

Encounters with André Breton and Paul Éluard (another lover) in 1928 sparked an interest in automatism and led to Agar’s inclusion – one of few female artists – in the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936. But Agar is unwilling to be categorised only as a Surrealist and argues for the compatibility of Surrealism and abstraction. She also casts a critical eye over the sometimes weak politics and double standards of her male peers: Breton’s wife Jacqueline was expected to play the muse rather than live her own creative life. In Agar’s interactions with the different coteries of European modernism, the artist’s spirit of play and deep commitment to her work is always palpable.

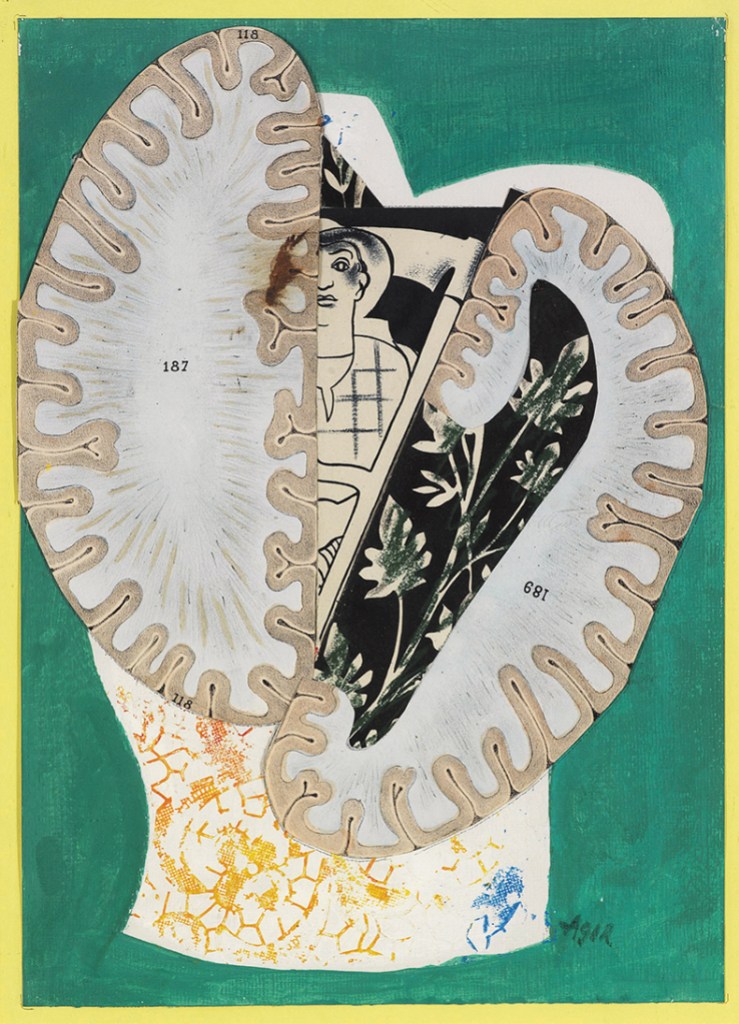

Apollo’s Lyre (1973), Eileen Agar. Redfern Gallery, London. Courtesy and © Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images

Agar’s own distinctive brand of Surrealism was largely drawn from nature and her desire for connection with the natural world intensified after the Second World War. She and Bard had been cooped up in a small London flat, working in the canteen service and as an air warden, respectively. She writes powerfully of living among the destruction while friends dispersed across Europe and America. According to Agar, few women produced ‘war art’, but her beautiful and buoyant painting Dance of Peace (1945) suggests a different kind of response to conflict, rooted in what she describes as ‘womb-sense’ and a commitment to ‘hope and celebration’ even in the context of the H-bomb.

The end of the war marked the beginning of her ‘wandering years’, with revitalising spells on the island of Tenerife. Colour floods into her work and vibrant collages respond to the ‘quickening pulse’ of the landscape. In the next two decades she experiments with acrylic, is included in numerous exhibitions and forges new artistic friendships, spending time with Ceri Richards and at Eagle’s Nest in Cornwall with Patrick Heron. She never seems to have lost the allure captured by Lee Miller and Cecil Beaton in photographs of her as a young woman; in her eighties she models for Japanese designer Issey Miyake.

‘We are not made of straight lines,’ Agar writes of the ways in which life takes on its own pattern and rules. Yet she adopts a largely chronological and, in some ways, surprisingly conventional approach to life-writing. Occasionally the voice feels uneven (Andrew Lambirth’s introduction describes the extent of their co-writing), but it is hard not to be drawn in by Agar’s often gloriously sensuous account of her life and art. Towards the end, she declares her credo: ‘Whatever you are going to do, you should do it here, on this planet, now. […] Listen to the things that whisper to you. They try to get through, but you get up and do something mundane like cutting the bread or answering the phone.’

A Look at My Life by Eileen Agar is published by Thames & Hudson.

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.