From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Mabel Barltrop believed that her garden at 12 Albany Street, Bedford, stood on the site of the original Eden. At her modern ‘Estate of Jerusalem’ a large weeping ash identified as the Yddgrasil tree (the ‘world-tree’ of Norse mythology), presided over the activities of the Panacea Society, a community of mostly middle-class women (and ‘a handful of men’) who recognised Barltrop as the ‘Daughter of God’. Between 1929 and 1932, the society hosted regular garden parties at Albany Street, offering believers a foretaste of eternal bliss: when the Lord returned, he would bring ‘potato races, clock golf, tennis darts, rings and putting and badminton’.

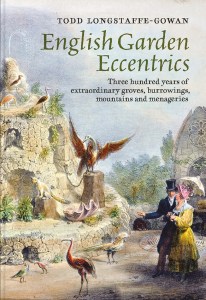

Barltrop’s Eden was a communal site, the borders of which waxed and waned as she annexed the gardens of various neighbouring members of the society. Ironically, given its biblical pedigree, the garden’s planting, like its parties, was strikingly conventional: the Yddgrasil tree rose from a lawn fringed with Edwardian-style flower beds. Formally, at least, this makes Barltrop’s millenarian garden one of the least eccentric to emerge from Todd Longstaffe-Gowan’s meticulously researched and beautifully presented cornucopia of idiosyncrasy. ‘Few spaces offer as many possibilities for self-expression as gardens,’ he writes, and the 21 short essays that make up English Garden Eccentrics explore how selected individuals have ‘used landscape to map out their personal biographies’. Eccentricity, described by the author as ‘an interstitial category somewhere between madness and dull normality’ first emerged as a concept in the early 18th century: this study spans the waterworks and automata of the ‘Enston-Rock’, created during the reign of Charles I by Thomas Bushell to the death of Mabel Barltrop in 1934.

For many of their contemporaries – as undoubtedly for the modern reader – the gardeners were at least as interesting as their creations. In Cumbria, the ‘yeoman’ Thomas Bland was so unkempt that visitors to his Italianate half-acre site populated with sculptures, paintings, a bandstand and a ‘little museum’ frequently tossed him a shilling for his trouble. In 1774, when Hester Thrale and Samuel Johnson visited the Romantic gardens at Hawkstone, Shropshire, with its ‘Awful Precipice’ and mechanical hermit, they were shown round by Jane Hill, whom Thrale found ‘uncommonly vulgar […] her appearance below that of a common house-maid’, but still ‘by far the most conversible Female I have seen since I left home’.

Longstaffe-Gowan’s subjects varied greatly in their attitude to visitors. At Walton Hall, Wakefield, the early conservationist Charles Waterton made his garden a haven for weasels, hedgehogs, ravens, magpies and owls, and his ‘Grotto’ available for ‘picnic parties’, with cups and fire for tea supplied in the nearby summer house. Conversely, at Cavendish Square in London, the 5th Duke of Portland, who acquired the sobriquet ‘the Burrowing Duke’ for the network of gigantic subterranean tunnels he constructed at Welbeck Abbey, Nottinghamshire, built an immense fluted glass screen and a colossal stable block around his residence to shield his activities from the curious.

The essays are sequenced thematically (topiary, menageries, caves and grottos, and the surprisingly numerous private projects of 19th-century society women). The result is to make transhistorical connections between successive stripes and generations of garden eccentrics. Many created miniature fantasies: Sir Charles Isham’s rockery at Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire, was one of the first gardens to feature gnomes, a variant on the ‘Gnomen-Figuran’ used as talismans by German miners. Sir Charles arranged them in tableaux among the rockwork: some had unionised, and were gathered around a placard demanding ‘Eight hours Sleep | Eight hours Play | Eight hours Work | Eight shillings Pay’. Similarly, visitors to Sir Frank Crisp’s Friar Park, Northamptonshire, could climb over a gritstone replica of the Matterhorn. Such miniatures, writes Longstaffe-Gowan, ‘remove the spectator from a sense of time and duration’, making the garden a virtually sealed environment in which to create an eccentric paradise. They also share a playfulness with another recurring feature, the topiary. In Worcestershire, Rachel Gurney, Countess of Dudley, gathered ‘verdant spirals, birds on pyramids […] and round ziggurats surmounted by peacocks’ in a section of the garden at Witley Court. Like Barltrop, she was acquisitive: rather than being clipped to order, her specimens were selected at maturity from the gardens of her neighbours and tenants.

While some gardens were spaces for play, others were devoted to more sombre contemplation. In 1728, Frances, wife of the antiquarian and vicar William Stukeley, ‘miscarried […] the 2nd time’ and Stukeley buried the ‘embrio’ in their garden at Grantham ‘in the chapel of my hermitage vineyard’, above ‘a camomile bed for greater ease of the bended knee’. At Denbies in Surrey, Jonathan Tyers established a sanctuary featuring a ‘Temple of Death’ and an archway comprising ‘two stone coffins, with human skulls placed upon them’ and accompanying admonitory verses. Denbies was a private moralistic pendant to Tyers’ public identity as the impresario behind Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. However, its function as a memento mori also reflects the garden’s subservience to what Longstaffe-Gowan refers to as ‘the evanescence of nature’. Recognising this, many (if not most) of his eccentrics regarded their constructions as perennial works in progress: the garden journalist John Claudius Loudon was repeatedly refused admission to Hoole House, Cheshire, because Lady Eliza Broughton had not yet perfected her vision of a miniature Swiss Alps looming over an array of circular flower beds.

Few of Longstaffe-Gowan’s subjects seem to have expected, or even desired, that their creations would survive them. As attested by a detailed coda summarising the present state of all these gardens, many have come down to us only through contemporary accounts. Most were the work of gardeners whose wealth and social independence allowed them full expression of their vision. This raises the intriguing possibility that for every delightfully bizarre construction in this book, there may once have been many more.

English Garden Eccentrics by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan is published by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies.

From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.