As for many millions of children before me, and millions since, Eric Carle’s story of a caterpillar’s quest for satisfaction, its guilty over-consumption and redemptive transformation into a beautiful butterfly, was seared into my young psyche. I don’t remember whether it taught me to count or whether I intoned from it the importance of following your instincts and the inevitability of change. What I do remember, aside from the joy of sticking fingers through the board pages’ die-cut circular holes, was the beauty of Carle’s textured, painterly collages, especially his renderings of foodstuffs. Having sold more than 170 million books throughout his career, including more than 55 million copies of The Very Hungry Caterpillar, his best-known title, Carle is hardly in need of further accolades. But he surely deserves credit for creating the most mouth-watering pickled gherkin in the history of visual art, knobbles and all.

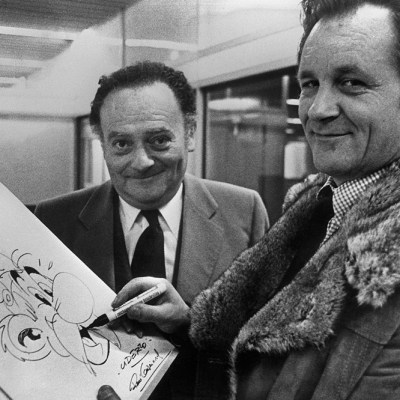

Photo: AFP via Getty Images

The genius of Eric Carle, who died in May at the age of 91 with more than 70 books under his belt, lay in his ability, through both words and pictures, to speak to children in a way that didn’t pander, patronise or moralise. He was able to find the perfect middle ground between simplicity and richness, creating something that was bright and appealing, but not at the expense of personality. Carle, whose own childhood in Nazi Germany was far from idyllic, managed to achieve in his bestselling story a message of hope without resorting to the condescending approach that plagues many books for children. While the more obvious message of the book is fairly conventional (that within us all is the potential to become something beautiful), the subtler messages were radical for their time in 1969 and remain relevant today. We all overdo it sometimes, we all feel guilt, we all long for solace in the familiar and everyone feels small and insignificant at times, especially during childhood. Most of all, sometimes we try and try again without finding any satisfaction.

Carle was sometimes philosophical about the meanings behind his beloved book – a perennial subject with interviewers – but more often than not he preferred to label any deeper meaning as ‘psychobabble’. He always stressed that the genesis of the book, which has been interpreted variously as a Christian allegory for the life of Jesus or a celebration of conspicuous capitalist consumption, came from absent-minded hole punching. From my perspective, having followed in its author’s footsteps by studying and working in the field of graphic design, what made The Very Hungry Caterpillar so successful was Carle’s natural ability as a visual communicator combined with his design experience. He appreciated the page itself as a canvas, the book as an interactive and tactile object, and text and image as elements that needed to work together to form an integrated whole. He even managed to make a serif typeface (something deemed un-child-friendly in today’s Comic Sans age) in black on a white background expressive and appealing.

Carle was born in Syracuse, upstate New York, to German parents, who, with his mother homesick, returned to their native country in 1935 when Eric was just six. Following a traumatic experience digging trenches as a teenage conscript during the war, Carle enrolled at the State Academy of Fine Arts in his hometown of Stuttgart, where he studied graphic design under the esteemed typographer and book designer F.H. Ernst Schneidler. After graduating, he freelanced as a commercial artist and soon found his work reproduced in Gebrauchsgraphik, his country’s leading design magazine. But America loomed large in his mind, both as the place of his birth and as the centre of post-war commercial design and illustration.

On moving to New York in 1952, Carle found work in the promotional department of the New York Times thanks to Leo Lionni, a designer who became a close friend and would also later find fame and a new career in children’s books. Carle and Lionni were far from alone; many leading mid-century American graphic designers, such as Paul Rand, Jim Flora, Ivan Chermayeff and Saul Bass, found children’s books to be a fulfilling and profitable way to apply their skills away from the world of business and commerce. For Carle it was a permanent career change, which came quite by chance. After leaving the Times he briefly served for the US Army during the Korean war and then worked freelance, mostly in the field of pharmaceuticals, designing and illustrating advertising campaigns for various medicines. It was one of these works – an expressive lobster illustration created from overlapping blocks of colour on a textural abstract background, designed for anti-allergy medicine – that caught the eye of the writer Bill Martin Jr., who asked Carle to illustrate his book Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?

Published in 1967, the book was an instant success and helped set Carle firmly on what with hindsight looks like an inevitable path. Ironically the life-changing lobster advert, the tagline of which read ‘when yesterday’s indulgence becomes today’s allergy’, was prescient of Carle’s greatest hit: illustrated literature’s greatest story of gluttony, the third book he illustrated and only the second he wrote himself. It has since been published in more than 60 languages, spawning a wide range of merchandise and adaptions, including a theatre production.

Unlike his nameless caterpillar protagonist, who tried, tried and tried again, Carle found a winning formula pretty much immediately. It was far from a fluke, though: The Very Hungry Caterpillar was published when Carle was approaching 40; years of making medicine visually appealing, which meant handling often difficult subjects, proved an ideal training for the subtle world of children’s picture books. His later titles often featured the trials and tribulations of small animals, but without ever feeling stale or repetitive. While many illustrated books from bygone eras have been rediscovered and republished in recent years, prized for their charming retro appeal, Carle’s classic title has never been out of print. It has a timeless quality that will always, no doubt, find it new generations of fans around the world; it is a lasting testament to his brilliance.

Theo Inglis is the author of Mid-Century Modern Graphic Design (Batsford).