From the July/August 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I saw Erin Shirreff’s work for the first time about 15 years ago at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Making my way through a show that included well-known figures such as Bruce Nauman, Allen Ruppersberg and Jeff Wall, I was struck by the subtly oscillating image of a mountain in a desert. I watched as hours – or aeons – passed by on a monitor, animated by a kind of internal weather, conjuring an expanse of space and time.

Roden Crater (2009) is the second in a series of videos that Erin Shirreff makes by animating found photographs with simple, hand-held lighting effects, photographing countless still images that she sutures together digitally to create an otherworldly atmosphere. With the most modest of means, Shirreff seems to find a way to illustrate how Heraclitus and modern physics have converged on the same idea: space and time are one. Her subject, she says, is contemplation. She wants the viewer to look and look again, to see how time is baked into objects and vice versa, to poke at truths beyond the grasp of our senses. The act of looking becomes itself a mode of thought, a way to find out how one thinks. I spoke to Shirreff before an exhibition of her work opened at the Milwaukee Art Museum (until 1 September).

I’ve tried to identify why your video Roden Crater grabbed me when I saw it at the Met, and I realised it must have something to do with the way you were able to conjure an illusion of enormous space and time, or duration, with the most modest of means. I’ve come to admire that sense of ambiguity or unknowingness in your work – of space and depth, of what we’re looking at, or when. So this is more of an observation that you can either reject or play with, but I would suggest that illusion plays an important role.

Yes, that is a concern that runs through my work. But I never want it to function as some sort of trick. I never want that to be the pivot. With Roden Crater or with, say, the folded photographs, where two halves come together over the seam of the photograph, there is a sense that what you’re looking at isn’t what you first imagined that you’re looking at. In both cases, it’s always for me in service to the kind of attention I want to elicit in the viewer – an extended attention. In those videos, Roden Crater and other videos that I’ve made in that mode, where photographs are animated through handheld light effects, there is, I hope, an experience of entering both the space of the image and then getting pushed back on to its surface. Scale comes into play because you slowly become aware of the size of the snapshot even as you’re drawn in to the scale of the landscape. The illusion – that’s the thing that invites you in.

When I mention illusion, I don’t mean you want to seduce the viewer too easily and then send them away feeling tricked. The word illusion is related etymologically to play. There’s a playfulness when you conjure sublimity at such a small scale. Was Roden Crater the first video you made with still images?

The first was based on an Ansel Adams photograph [Ansel Adams, RCA Building, circa 1940 (2009)] – a big blank facade of a building. I was staring at this photograph in the studio from this old MoMA publication and, as I stared at it over the course of the afternoon, the light in my studio shifted and seemed to affect the ambient light within the photograph. And it was this effect that I then tried to record, setting up my camera and taking a series of still images. That evolved into a more intentional process with Roden Crater, which was the second one that I made. That process differed slightly, but it’s the same idea – there is this interior space of the photograph and then the acknowledgement of the source material, the printed artefact.

Do you think if you hadn’t trained as a sculptor that you would have noticed that? A photographer might have looked away or observed that the light was just shifting off the surface. But as a sculptor, you imagined the space of the photograph as concrete.

I think that’s part of it. I don’t have the sensitivity of someone who is trained in photography. I wouldn’t have the immediate technical engagement with the image. I’ve had many formative experiences in libraries, in the stacks, going from book to book, flipping through the pages, looking at things, engaging with images – images of artworks, but also images on pages. And it’s a different mode of absorption and attention when you’re having that tactile experience with an object. And there was, at that time in my studio, the imprint or the shadow of the screen from the window. All of those things became part of the experience. I guess that if I’d studied photography, I wouldn’t have picked up a book that had Ansel Adams in it.

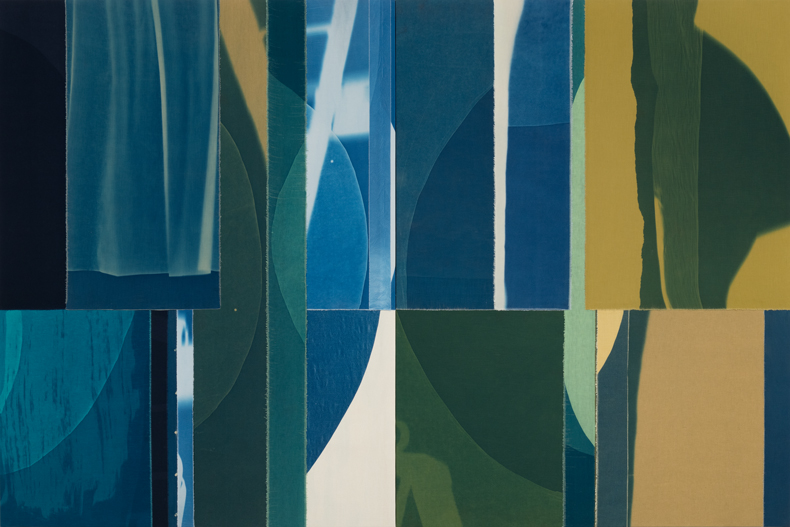

Right, he’s way too calendar-friendly for a student of photography. The description of your experiences in libraries leads me to another question – the sense of belatedness in your work. The videos Roden Crater and Ansel Adams, and Lake (2012) and Medardo Rosso, Madame X, 1896 (2013) have a ghostly quality, and the source material of the dye-sublimation collages is taken from art history catalogues, scanned, blown up and reprinted. That sense of being adjacent to time or belatedness even appears in some of your titles. One cyanotype is called Inside times (2020), another is Echo Exposure (2019), and there’s a dye-sublimation print titled Old Friend (2022). We live in an age when everything seems available – and yet everything has already happened. Your work invites the viewer to look at history not as a series of events but as a texture, a sensation that haunts the present.

When I make the dye-sub collages, using strangely coloured, degraded images, or fragments of images, what I’m pushing towards is a physical form. Even though it’s made very clearly out of flat, fragmented snippets, and the coloration of the images tells you of its historical origins, I want them to coalesce into a new, strange form that pushes out into a different dimension. You said when you were looking at them that they had an atemporal feeling. I like that. You can’t really say that it’s the ’80s or the ’90s or this or that era. There is a sense of placelessness.

But then you add a layer of your own, an emulsion of time. You take that experience of looking at the work of other artists, in books or elsewhere, layer it with an interpretation, transforming it into your own work.

I want to undermine the sense that I’m making art about art. A friend said something to me a number of years ago, and it stayed with me because I think it’s true: he said I use art as subject matter because art is an object of contemplation and my subject is contemplation. I worked for a long time in museums and I watched people look at other people’s work, wondering what was happening in that experience or encounter, then reflecting on my own impatience with objects, noting when I was absorbed and when I wasn’t. I was grappling with how to make work, thinking about my own experiences with other works. I mean, the reason we’re in this game, I think, is because the language of art is so large. It is so untraceable, it’s so unnameable, it’s beyond language.

That reminds me of something else I was thinking about while preparing to talk to you. In the back of my mind was this quotation from Nicolas Poussin, a passage in a letter. He made ‘a profession of mute things’, he wrote. Muteness is a kind of force in your work as well. There’s such a sense of potential energy in the videos and sculptures, and yet they’re dead quiet. I don’t know if that feeling of muteness is interesting to you.

Yeah, that’s great. I made a video a few years ago that’s in a different mode to the others, a sort of unending scroll of forms that move across the screen, called Still (2019). Someone described it as having a ‘deafening silence’. Apart from the fact that 99.9 per cent of the videos that I’ve made don’t have audio, I’m interested in that notion in a more abstract way. There’s a bid for me to get at this register of being or affect that has an enduring quality, a static enduringness that I’ve always been attracted to, that I hope is alive in the experience in my work.

Maybe we could take up this idea about muteness through your series of sculptures called Drops. If you see them from one angle, they’re almost picture-like, reminiscent of an abstract painting. But if you stand back from and look at them straight on, they’re porous. They bend in space, yet they’re flat. They play with that range of paradoxes that we’ve been talking about – of space and duration, object and image, and they are difficult to place, historically. They may be mute, but they demand a lot of the viewer.

For me, the more recent Drops are more directly an outgrowth of this mode of making in my studio – a sense of play, if you want to use that word, like they are coming out of this process of reconstituting scraps, which has become a sort of theme in my work. It’s a series that I’ve been engaged in for a number of years, in different modes. The Drops in my most recent show, and that will be on view in a different formation in Milwaukee, emerge from the leftover shapes from the dye-sublimation cutting process for the collages. The negative space in the panels has a direct relationship to the shapes that I used in the collages. The shapes and forms are translated into Cor-ten steel, and the fragments have a physicality, even though they’re very thin things, through the sort of factualness of this heavy sheet metal. But they are more about the absences, the negative spaces within the rectangles, than they are about the material themselves. Their form implies a sense of temporary composition. The show in Milwaukee is called ‘Permanent Drafts’, and the installation of the Drops at the museum will be a site-dependent installation of these shapes in a unique arrangement. I like the suggestion of contingency for this work. It’s sculpture in a more traditional or conventional sort of way, even though it’s leaning against the wall, even though it’s very frontal. You can’t walk around them, which is what people expect out of a sculpture. They still have a factualness because they aren’t pictures – they don’t have the remove of the dye-sub prints. They’re right there, objects in the space. I like this way of working with doorways, thresholds or apertures within the metal. That central compositional force in the work – that’s new to me and I’ll continue to work with it.

The Drops, of all your recent works, despite their heaviness or ‘factualness’, remind me of some of your most modest work, such as the Pages and other small collages. You just described the chunks of Corten steel as scraps or fragments, and the Pages works are also made from scraps or fragments of books or catalogues. How do you relate the brute heaviness of the Drops to the sense of belatedness or virtuality of the Pages?

Something that I find myself gravitating towards is the thinness of the steel and the light, curved cutouts versus this rigid, heavy, factual material. I don’t have a metal yard in the back of my studio – I do a lot of mock-ups in lighter material and then have it translated into the metal. That translation is important to me, as well as the fact that they present a very frontal experience, and a completely different sideways experience. Viewed in profile, they’re very inconsequential things. And then as a viewer passes by them, they offer a range of different registers.

This relates to your durational videos, and so much of your work for that matter – the work offers a way to think about the time we spend looking at objects, or how we consider history. The sculptures, the videos – they all demand focused attention over time, demand we look from different perspectives. Perspective and contemplation combine in your work to slow time down, open up a space to think, or to think about thinking. I’ve never had this thought about your work before, but in terms of the time we spend looking or thinking with any depth or seriousness, the works are also modest epistemological proposals. These are aesthetic concerns, but there’s a political angle as well.

People complain about museums and galleries all the time, that they are elite spaces, et cetera, but the number of spaces in which the public is allowed to think without a script at this point is vanishing. I have always found those experiences, those spaces, very meaningful. They allow me to be bored. They allow me to connect with myself and to discover my own thoughts. The internet is everywhere, in every space, but in museum and gallery spaces you privilege looking and walking and thinking. This stuff is important. And I guess it’s politically important because you find out what you actually think.

‘Erin Shirreff: Permanent Drafts’ is at Milwaukee Art Museum until 1 September. Shirreff’s work is also at von Bartha in Basel from 28 August to 17 October.

From the July/August 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.