This review of The Uglow Papers by Andrew Lambirth (ed.) appears in the January 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Teaching in the Slade School of Art’s ‘F’ studios – its ‘figurative’ department – was dominated for almost 40 years from 1961 by Euan Uglow, who had himself trained there in the early 1950s. The painter’s methodologies and decisive vision pulled students along with the power of a tugboat, the ripples from which still show up on the walls of certain British galleries. Today, however, for all that figurative painting is to the fore, Uglow’s art has come to look half alien. The ferociously inward-turned enquiries of his canvases – how shall the observed sitter and the canvas edge relate? How shall each patch of colour abut its neighbour? – feel marginal to contemporary dialogues that turn on memories, histories and cultural resonances. Uglow’s avowed appetite for able-bodied naked women, often asked to strike strenuous poses, stands likewise at an awkward angle to current priorities.

An upcoming survey of Uglow’s art at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes (14 February–31 May) may bring it better into focus. Beforehand, Andrew Lambirth, who became a friend of the artist in the late 1980s, has compiled a wonderfully evocative volume of witness statements. The studio leader’s voice and presence come through in reminiscences by many a Slade alumnus: the stocky South Londoner who would every Friday pad between the easels in desert boots, puffing at his Gauloises, exhorting students to behave ‘morally’ with paint, scolding one for having missed ‘the relationships’, pouncing on another’s study with ‘Why is it so boring?’

There’s near-consensus on the epithet ‘bossy’, yet there’s huge fondness too. Five o’clock on those Fridays and corks would pop, convivial boozing begin, often leading to meals: besides Uglow’s capacities as a motor mechanic and carpenter, the memoirs testify to his outstanding cooking and his connoisseurship of wine; most of all, to his gift for friendship. While hardly sexually loyal (there was a single brief attempt at marriage), he would reliably show for your private view, send you his handmade Christmas card, demonstrate attentive respect. Within this volume, at least, the women he persuaded to contort themselves forgive him their back aches.

But what did it mean, to paint ‘morally’? If senior example shapes a person’s morals, then William Coldstream, whom Uglow followed from Camberwell Art School to the Slade, would seem Uglow’s obvious mentor, with his devotion to step by step, mark by mark investigation of what actually lay before the eyes. The ‘relationships’ that both artists aimed to nail were between points and boundaries within a field of vision: the seeming objectivity you attained by securing them lent the method an appeal to many followers. Lambirth’s contributors suggest however that Uglow himself was other than a direct disciple. Robert Dukes posits that he owed his developing taste for clean, decisive colour contrasts to Claude Rogers, while Tony Rothon thinks that the theory-minded Myles Murphy steered him towards the geometries he employed to tamp his figures down within their frames.

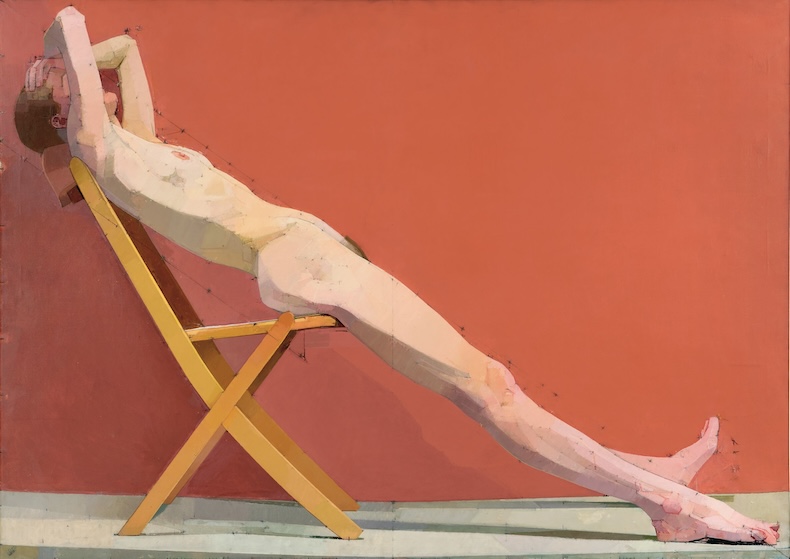

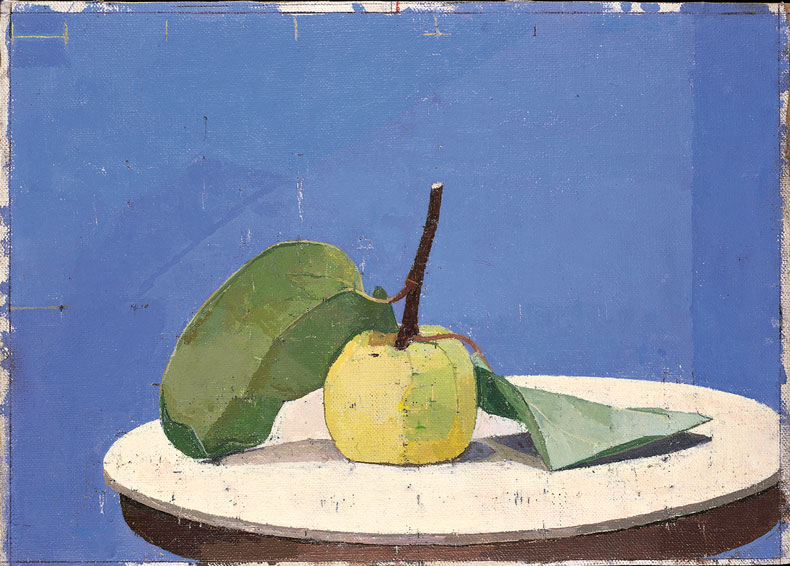

These agendas fused in a body of work that is as loud and arresting as anything in 20th-century observational painting. In the still lifes and female nudes Uglow painted in the four decades before his death in 2000, high-pitched hues jolt the eyes and the painter’s enquiries become declamatory: it is needful that the object and the space behind it interact exactly so, it is needful that limbs and torso interlock in this or that closed form. These proclamations could in turn become puzzling: what kind of necessity is this? What truth or ethical aim is thereby delivered? What have golden sections or square-root constructions to do with the givens of daylight and live bodies?

It’s a virtue of The Uglow Papers that the dossier mulls over these questions while leaving them open. On one level, Uglow’s art might seem a forthright celebration of suspended desire, in line with his declared intent to display on a flat surface what made a subject ‘look so marvellous’ and with his advice to Chris Bennett, a student of the 1980s: ‘What is the most important thing in your life? Is it cars? Girls? Football? Food? Find out what it is and paint that.’ Bennett posits the reasoning by which Uglow devised a method arising from these impulses: ‘Geometry was a tool with which he constructed a paradise in faithful parallel to the model’s unassailable miracle of existence.’

This constructing, at the same time, could be giddily extreme: in Summer Picture (1971–72), for instance, Uglow painted a bowed nude seated in profile on a tabletop, but re-carpentered the latter to splay backwards, so that its receding edges, once observed, would fit the canvas more harmoniously. The ‘paradise’, as Lambirth notes, had an arduous and even aggressive aspect; he also notes its ‘forcibleness’. The art writer would hear the older Uglow express a wish for the work to become ever more ‘thorny’, in the manner of Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. It is not surprising that some students or subjects recoiled. Laetitia Yhap, once Uglow’s model, took off with Jeffery Camp in whose canvases there was by contrast ‘air circulating’. Michael Ajerman, a New York student on exchange to the Slade in 1999–2000 – one of many who would detach Uglow’s personal decency from the imitative behaviours his charisma aroused – recalls the ‘F’ studios as a redoubt of outmoded and ‘quite fascist’ beliefs. Perhaps we are at sufficient distance now to look afresh. Lambirth’s finely delivered volume suggests that we will come up against a stimulus and challenge, mysterious and undismissable as only the strongest painting is.

The Uglow Papers by Andrew Lambirth (ed.) is published by Modern Art Press.

From the January 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.