Of the masses of people queuing up these days at MoMA to purchase museum tickets, the great majority is vying for timed spots at the globally-acclaimed Matisse show. There is, however, a select group of museum-goers who are drawn in not by Matisse, but by his wilder and more macabre contemporary Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. For awe-inspiring though the Matisse show may be (yes, it is absolutely true that the swimming pool alone is reason enough to see it), there is a far more complex and, ultimately, rewarding viewing experience to be found in the relative calm of ‘The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters from the Museum of Modern Art’.

This exhibition – the first monographic show of Toulouse-Lautrec’s work at the MoMA in nearly 30 years – offers neither an exhaustive catalogue of his production nor a revolutionary reconsideration of this fascinating figure. Instead, ‘The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec’ deftly reacquaints us with the artist and his moment, reminding the viewer of the true extent of his maniacal talent.

This re-presentation of Toulouse-Lautrec’s work has a decidedly historical bent; indeed, the artist’s work and life are nothing if not reflections of his own time, even down to his distinctive physical appearance. The son of aristocratic first cousins, a match which left him abnormally short-statured and with disproportionate facial features, Toulouse-Lautrec the man emerged as a kind of allegorical figure of fin-de-siècle Paris, with its penchant for excess and simmering anxieties about the degeneration of western culture. His work, too, rooted as it was in the unique culture of the Parisian boulevards and the dubious entertainments of the café-concerts, offers a fascinating glimpse of contemporary society.

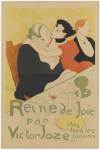

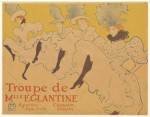

The show does an excellent job of incorporating materials in a variety of media (including photographs, film, and digitised books) to situate Lautrec’s own multi-media production, which included everything from playbills to paintings but predominantly posters and lithographs, in his historical milieu. There is no better artist than Toulouse-Lautrec to bring both sides of the Parisian Belle Époque – the dark and the luminous, the decayed and exuberant – to life a century later, and he certainly does so here.

Installation view of ‘The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters’ at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (26 July, 2014–22 March 2015). Photo by John Wronn © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art

Click here for a gallery of highlights from the exhibition

Ultimately, however, what makes ‘The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec’ so compelling is not the coherence of its cultural contextualisation, but the show’s acknowledgement that history must at times play second fiddle to artistry. In the breathtaking wall of lithographs from the series Elles, the works are given the physical and intellectual space to stand alone as well as in dialogue with each other. In this dialogue, a grace and tenderness emerge that are in total contrast to the violent splashes of colour and grotesque lines that dominate Toulouse-Lautrec’s best-known posters.

Of course, not all the credit should be given to the curating: it is ultimately Toulouse-Lautrec himself who elevates posters and playbills above the status of cultural detritus. Nowhere does his talent speak more clearly than in the remarkable lithograph he made of the dancer Loïe Fuller. As a historical artefact, it rivals the accompanying film in its documentary ability to capture the variations of Fuller’s movement in shades of black and white. Far more importantly, however, it rivals – if it doesn’t exceed – Toulouse-Lautrec’s more trumpeted upstairs neighbour at the MoMA for its uncannily moving, completely riveting, and decidedly modern sensitivity to the simple beauties of line, form, and abstraction.

‘The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters’ is at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, until 22 March 2014.

Related Articles