From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Shot from behind, the man is seemingly levitating, though he’s wearing ordinary clothes and is in an unremarkable landscape. Actually he’s simply been caught mid-jump but, by freezing an instant, the photographer, Julie Borissova, has transformed it. Held in suspended animation, the man seems to defy gravity. The image floats the possibility that he won’t fall.

The photograph is part of Borissova’s series J.B., about men floating in the air, and appears on the cover of a book called Running Falling Flying Floating Crawling, edited and published in 2020 by Mark Alice Durant, which includes many other tantalising images and accompanying essays. An unknown photographer in the 1930s has captured an unknown girl in a bikini, propelled elegantly aloft; Denis Darzacq presents people suspended, Exorcist-like, in the supermarket; in I Throw Myself at Men, Lilly McElroy reimagines the phrase associated with embarrassing desperation in a series of powerful superhero poses.

From Muddy Dance (2021) by Erik Kessels, published by RVB Books.

It’s the same in Muddy Dance (2021), a book of sports photographs put together by Erik Kessels, which shows footballers sent flying and at their most balletic. Meanwhile Falling (2021), a photobook by Gabby Laurent, depicts the artist coming a cropper in a variety of ways – down the stairs, off her bike, up the kerb, and so on. Laurent’s images tend to catch the end of the trajectory, the point just before hitting the deck, so you may feel some sympathy for her. But she’s playing with the idea of control or the lack of it, because these are pratfalls she has planned.

Photographers have been capturing people in mid-air for as long as cameras could move fast enough to do it – as the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, André Kertész, and Eadweard Muybridge shows. The latter, Durant writes, hangs over the field ‘like the bachelor uncle who shows up at every party bragging that he had done it all before’. As far back as the 1870s, Muybridge settled a long-running debate by showing that horses lift all four hooves in the air when galloping; his seminal work Animal Locomotion (1884–87), which was made for the University of Pennsylvania, shows humans and creatures in motion, step by step.

From Falling (2021) by Gabby Laurent, published by Loose Joints. Courtesy Loose Joints; © Gabby Laurent

Muybridge’s images were intended for scientific study, offering proofs by dividing and recording reality. Rebecca Solnit has made the point that he was carving up time just as robber barons were dividing up the American West – taking control of space and time and ordering them into neat grids. But if these images are about control, somehow they also evade it. The application of science creates something otherworldly here, suggesting people can fly, or levitate, or simply defy gravity. If they’re fragments of evidence, they’re seriously misleading. If they’re documentary shots, somehow they’re also fake news.

‘It is impossible to say anything about that fraction of a second when a person starts to walk,’ wrote Walter Benjamin in A Short History of Photography (1931). ‘Photography with its various aids (lenses, enlargements) can reveal this moment. Photography makes aware for the first time the optical unconscious.’ For Benjamin, such images show ‘the difference between technology and magic to be entirely a matter of historical variables’, and in doing so they show something uncanny, perhaps; the return of the repressed or a vision of something usually seen but not seen.

For Benjamin this had revolutionary possibilities, the potential to shock viewers out of more familiar interpretations of the world. But, he added, these images need captions, if they are not to ‘remain stuck in the approximate’; these slithers of life need to be tied down, so they don’t float off into the unknown. Susan Meiselas of Magnum Photos might agree. One of her best-known photographs, included in Durant’s anthology, shows a man with a gun, hopping up on to a kerb; the image is titled First day of popular insurrection, August 26, 1978, and it comes from Nicaragua, a series of photographs Meiselas took over a whole year and published as a book in 1981. The man ran past in an instant, but Meiselas later met his mother and found out more about him; he was a Sandinista called Ernesto Cabrera who was just 19 when she saw him and 25 when he died.

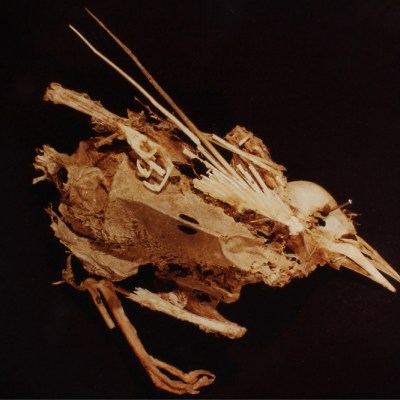

Plate 626 from Eadweard Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion. An electro-photograph of consecutive phases of animal movements. 1872–1885. Photo: Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

For Meiselas, it seems, the moment was not enough. Her caption states where and when she was working and what was happening; she found out who she had photographed and what he was doing. She also found out what happened next. ‘It’s true that photographs stop time,’ she comments in Pictures from a Revolution (1992), the film she made about her Nicaraguan work. ‘But for people, time doesn’t stop. Maybe photographs tell a kind of truth about the moments they fix. But is it enough of a truth? And for people, who must live in time, is that truth of any consequence?’

It’s a good question and one that haunts the photograph known as The Falling Man, by Richard Drew of Associated Press. It captures a figure plummeting from one of the World Trade Center towers on 11 September 2001, plunging headfirst and strangely still, though the wider sequence shows that he was tumbling. The man was never formally identified and the image became somewhat taboo; in the reporting on 9/11 it was published just once in the New York Times, for example, such was the outcry. In this case readers were only too aware that the photograph was misleading. They knew that this moment was a moment, and knew the context even without a caption – this man kept falling and died because of it, as did so many others.

Perhaps all scenes of falling, even those that have more levity, carry some weight. There’s the same knowledge of the inevitable downturn, and perhaps that’s what makes them resonate now. We’re still in the throes of a pandemic, which may augur more ecological meltdowns to come. Our lives have been thrown up into the air and we’re still not sure where we’ll land.

Crawling by Mark Alice Durant (ed.), is published by Saint Lucy Books; Falling by Gabby Laurent is published by Loose Joints; Muddy Dance by Erik Kessels (ed.) is published by RVB Books.

From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.