It begins, as these things often do, with a map. Bernard Sleigh’s An Ancient Mappe of Fairyland newly discovered and set forth (1918) is a huge slab of Edwardian whimsy depicting everything from Atlantis to Humpty Dumpty. Here are the ‘realms of imagination’ referred to in the subtitle of the British Library’s ‘Fantasy’ exhibition: vast expanses indeed, synthesising myth, allusion and invention in a fanciful topography. Sleigh’s map might be promising us an escape, like an illustrated map in a travel agent’s office – but mapping can also be an avaricious exercise, a prelude to annexation.

An Ancient Mappe of Fairyland newly discovered and set forth (1918), Bernard Sleigh. Photo: © British Library Board

Not just a map, but an ancient mappe – the slightly dubious claim to antiquity is also a fantasy staple. Fantasy, though, is truly ancient, providing that we regard its border with myth to be highly porous: the oldest work on display here is the epic of Gilgamesh, demonstrating what a fundamental and universal narrative the hero’s quest is. Arguably ‘fantasy’ as a type of writing emerged when creators became conscious of the plasticity of myth and its susceptibility to invention and reinvention, and realised that the atmosphere of the antique and half-forgotten could be productively draped over anything they created. The word has connotations of an unwilled dream-state. Beyond the Ancient Mappe, one of the first things the visitor sees is Richard Dadd’s crowded, gem-like and disturbing painting The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (1855–64), made while he was an inmate at Bethlem Royal Hospital, which suggests a touch of unreason as well. But in truth it is an acutely self-conscious genre, a fact ‘realms of imagination’ teases out quite well.

Exhibitions at the British Library are sometimes slightly hobbled by the limitations of the book as a form: triumph of civilisation it might be, but you can’t absorb it all at once in an exhibition setting. Without prior knowledge, you’re reliant on covers, bindings, sample spreads, marked-up manuscripts, secondary works of art and the curator’s say-so. Here, though, the self-conscious nature of fantasy is a tremendous advantage – fantasy books are in general keenly aware that they come to you as books, and they revel in the trappings and foibles of the book form. Hence the maps, and invented epigraphs and historical notes, and the tendency of covers to be printed like ancient tomes, and the fact that it’s not just children who get to enjoy numerous illustrated editions.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (15th century). Photo: © British Library Board

And so, curators Tanya Kirk and Matthew Sangster have a great deal of bibliophile material to draw upon: fantasy is a genre that revels in exquisite, richly-decorated special editions and in the scribbled and the inky and the hand-made. A 15th-century edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight shows the way – a heroic quest, of course, but quite aside from the story there’s the atmosphere of the volume itself, crabbed and palpably ancient, its naive painted pages visibly handled by many hands. The object is as atmospheric as the tale. Fantasy orders a certain kind of creation – you can see it in the microscopic handwriting, fake frontispieces and hand-drawn maps of the Brontë sisters’ girlhood Glass Town stories of the 1820s, and in Jeannette Ng’s cramped notes for Under the Pendulum Sun (2017), with their chatter of possibility, improvisation and allusion. Even when the words are being silently served by word-processor and printer, the atmosphere hangs heavy.

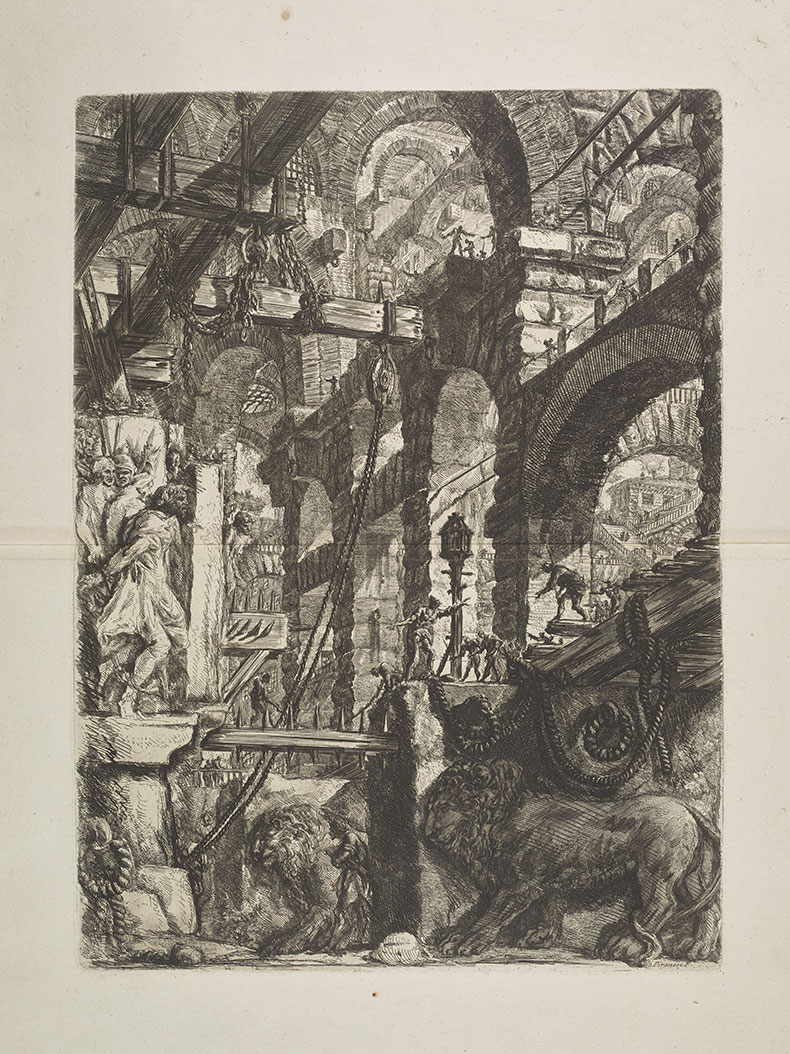

Carceri d’invenzione (1750–61), Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Photo: © British Library Board

The creation of new worlds does also necessitate a good deal of record-keeping and paper-based problem solving, which can be fascinating to examine. A highlight of the whole show is Susanna Clarke’s exquisitely neat diagram-map of the setting for her novel Piranesi (2020), and accompanying tide chart – too much of a spoiler to include in the book, where it would break the mystery, but evidence of the deep care that went into giving that mystery a firm scaffolding. It is displayed, of course, next to a second edition of Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Carceri d’invenzione (1750–61) – a little on the nose, but in this case that’s a good place to be, given how much fantasy has emerged from those dripping cyclopean stones.

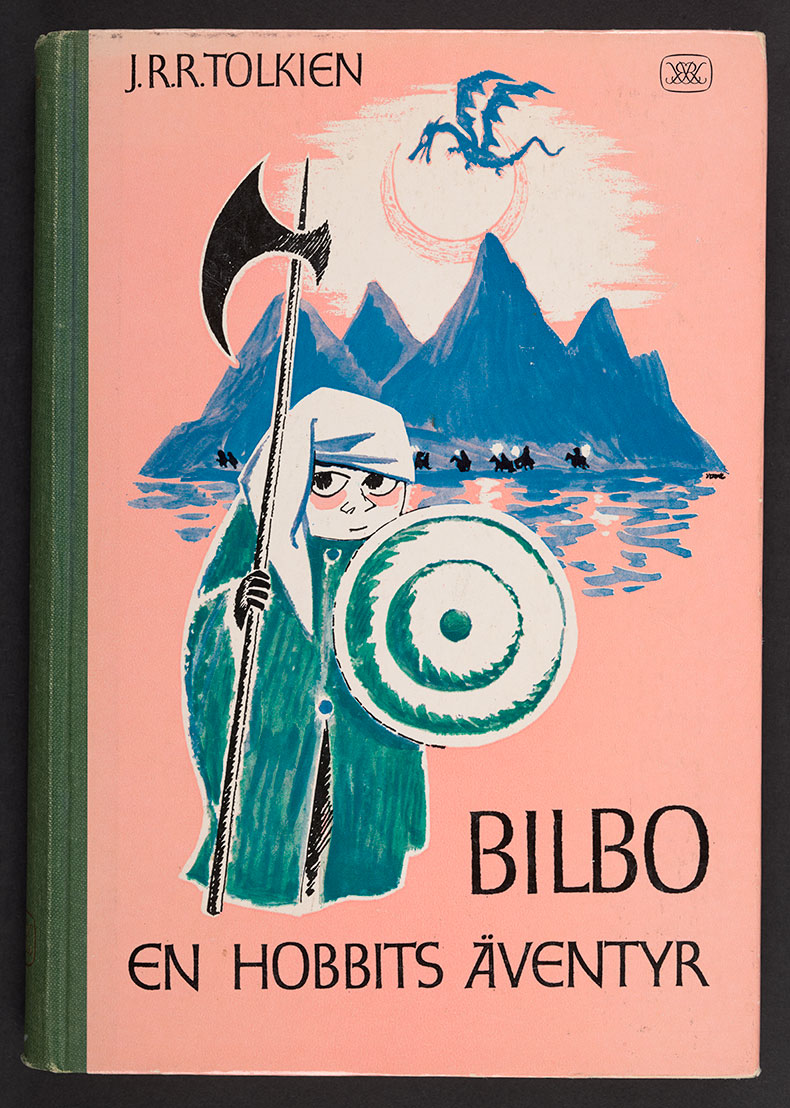

Fantasy authors also often illustrate their own work, famously so in the case of J.R.R. Tolkien and Mervyn Peake, and what a delight it is to pore over Peake’s feverish and atmospheric drafts, in which sketches and text form a frantic unity. The Tolkien presence is firmly limited, which might be owing to the jealous nature of his estate, but is a wise decision in any case as he can overshadow any discussion of this subject. (A more recent boy wizard is also given no more than a judicious nod.) This clears the path for the unexpected, such as G.K. Chesterton’s sketches of scenes from The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare (1908), with wonderful characterful faces and kinetic lines. And rather than Tolkien’s own drawings, we get Tove Jansson’s splendid 1962 illustrations for a Swedish Hobbit, showing a giant Gollum rising like a pillar of ooze from a cave pool.

Bilbo: En Hobbit’s Aventyr, front cover designed by Tove Jansson (1962). Photo: © Tove Jansson Estate

According to the caption, Jansson’s Gollum prompted Tolkien to add the word ‘small’ to later editions. Such preciousness is a losing battle. This is a genre that invites the closest and most intimate reading, and the author is necessarily surrendering their work to the reader’s own personal limited edition. This intense engagement is nothing new, as a page from a 14th-century Iliad makes clear – even the annotations have annotations. It is brought completely up to date with a concluding nod towards modern fan culture, live-action role-playing and fan fiction, in which readers write their own unauthorised stories featuring the characters they love. Fantasy in other contemporary media – film, computer games, board games and so on – is given well-judged appreciation. And the exhibition design, by Drinkall Dean, is excellent, making full use of the high ceilings of the gallery space to suggest forests and ruins, and contributing nicely to the mood.

One shortcoming of the exhibition is its patchy recognition of the artists who illustrated so many of these works. For instance, a 2003 Folio Society edition of T.H. White’s Arthurian fantasy The Once and Future King (1958) is opened to a woodcut depiction of the wizard Merlyn’s upstairs room – unless I missed something, the artist is not mentioned in the accompanying caption. It is John Lawrence. It might not seem important to state that Edward Miller painted the cover art of the first paperback edition of China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station (2000) – surely it’s the text of the book that truly matters? – but for many of us this was our first taste of the city-state of New Crobuzon, the reason we picked that book off the bookshop shelf, and an image that indelibly marked the reading experience. This visitor was in transports of nostalgic delight poring over a display of painted Warhammer armies, but it might have been fitting to credit some of the artists and designers who shaped those influential little lead figures, such as the British illustrator and modeller John Blanche. These lapses fit with the less glorious tradition of fantasy towards heavy borrowing and forgetting proper attribution, and it might seem like pedantry to grumble about it. But the rather sordid treatment the pulp and paperback industries meted out to remarkable commercial artists in the past, combined with the incalculable contribution they made to the readers’ imagination, means nowadays we should be doing more to recognise and remember their names.

‘Fantasy: Realms of Imagination’ is at the British Library, London until 25 February 2024.