Edinburgh Art Festival is a little more integrated into the city’s life either side of August than its counterparts, the International Festival, the Literary and Television Festivals, and the dreaded Fringe. As well as the various pop-up displays and specially commissioned pieces, its programme includes several of those exhibitions already running in Edinburgh’s museums and galleries. These and other shows celebrating past masters provide residents (and indeed visitors) with respite from the annual onslaught of contemporary culture, not to mention the deluge of tourists and mime artists, student theatre groups, stand-up comedians, and friends who ignore you for the rest of the year but suddenly get in touch just before August, wondering if you have a spare room going…

*

This summer’s blockbuster exhibition is ‘Beyond Caravaggio’ (until 27 September) at the Scottish National Gallery – the emphasis here being on ‘beyond’. It is an exhibition less interested in the famous artist whose name draws the crowds, than the art-historical context in which he operated. Caravaggio’s influence on European art following his death in 1610 is mapped, in certain places more convincingly than others, through Caravaggisti as far flung as the French Georges de La Tour, the Dutch artist Gerrit van Honthorst and Caravaggio’s fellow Italian Guido Reni, whose skull the great man is said to have threatened to split if he didn’t stop imitating his style.

Compelled to leave first Milan, for assaulting a police officer, then Rome, for killing a man in a row over a tennis match – so the story goes – Caravaggio’s colourful biography has often seemed inextricable from his work. This is partly because he used himself, as well as many of the card-sharps and prostitutes with whom he associated, as models to spectacular effect in his epic, roguish biblical scenes. So it is intriguing to see how his influence was understood by associates such as Reni, or his lover and sometime model Cecco del Caravaggio. There are fewer works by Caravaggio himself on display here than in the exhibition’s previous incarnation at London’s National Gallery, the number dropping from six to four. But paintings such as Boy Bitten by a Lizard (1594–96) and The Taking of Christ (1602) are enough to justify the admission fee alone – providing striking examples of those qualities to which later artists, operating in the intense shadow of his almost flamboyant chiaroscuro, were so indebted.

Boy bitten by a Lizard (c. 1594–95), Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. © The National Gallery, London

*

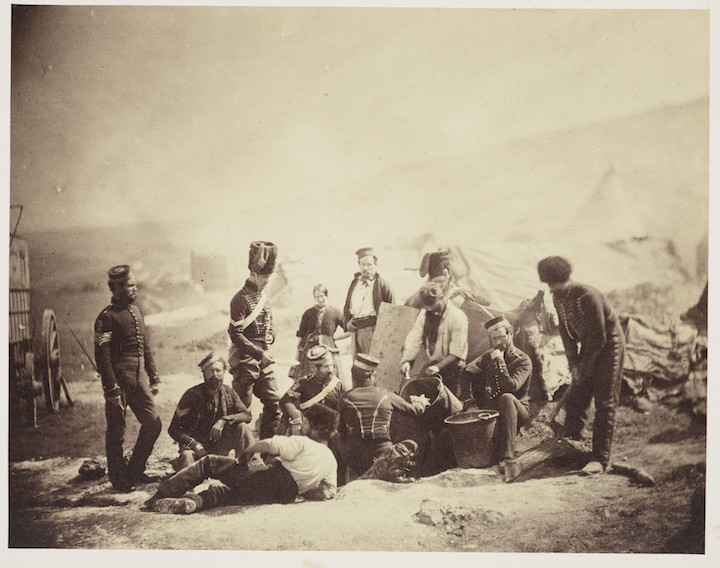

‘Shadows of War: Roger Fenton’s Photographs of the Crimea, 1855’ (until 26 November) at the Queen’s Gallery at the Palace of Holyrood House is another exhibition worth catching. Bleak but full of personality, Fenton’s photographs capture both the tragedy and the absurdity of that conflict. The diminutive figure of the Ottoman commander Omar Pacha, photographed in Council of War held at Lord Raglan’s Headquarters the Morning of the Successful attack on the Mamelon, looks like an anxious child at a fancy dress party, sat between the one-armed Raglan and the portly French Marshal, Pélissier.

8th Hussars Cooking Hut (1855), Roger Fenton. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

*

Also fascinating is ‘True to Life: British Realist Painting in the 1920s and 1930s’ (until 29 October) at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, which I’ve reviewed in more detail for Apollo elsewhere. The exhibition is an attempt to restore the reputations of artists such as Meredith Frampton, Winifred Knights, and Gerald Brockhurst, whose quiet technical accomplishments and contemporary success have been overshadowed by our sense of the interwar period as a modernist moment.

The Snack Bar (1930), Edward Burra. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London

*

The National Museum of Scotland’s ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites’ (until 12 November), is the largest exhibition devoted to the Jacobites since 1946, when the Scottish National Appeal for Boys Clubs marked the second centenary of the Battle of Culloden with a collection of ‘Jacobite relics and rare Scottish antiquities’. There is a good deal of Culloden memorabilia among the over 350 objects on display, some of it ghoulish: the block on which many of the Bonnie Prince’s supporters were beheaded is here, loaned by the Tower of London. But Bonnie Prince Charlie and his fellow Pretenders spent only a small proportion of their time in Britain, actively trying to regain the throne (just 14 months in his case). Much of the rest was spent on the continent, under the protection of a series of European potentates. This exhibition is among the first to place equal emphasis on their exile. Bonnie Prince Charlie’s brother Henry’s diamond-encrusted gold communion set (on loan from the Vatican), is a highlight, displayed alongside items loaned by several other collections across Europe, including the Louvre.

Henry Stuart ended up as a cardinal. Ironically, it was the very richness of the Jacobites’ lives in exile, and the complexity of their allegiances, that undermined any attempts to reclaim what they considered their birthright. You can draw a direct line from the communion set to the execution block.

Bonnie Prince Charlie Entering the Ballroom at Holyroodhouse (before 1982), John Pettie. © National Museums Scotland

*

‘Looking Good: The Male Gaze from Van Dyck to Lucian Freud’ at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery (until 1 October) is another testament to curatorial ingenuity. The exhibition is built around the recent acquisition of Anthony Van Dyck’s final self-portrait (c. 1604) for £10 million by the National Portrait Gallery in London. The SNPG is the final stop on its national tour, each stage of which has seen it exhibited with a different selection of paintings. Here it is used to gently challenge the prevailing critical emphasis on male objectification of the female form in western art.

The objectification of the male form is traced through 29 artworks: portraits of 17th-century courtiers, 18th-century dandies, and 20th- and 21st-century celebrities. We travel from Van Dyck’s portrait of the Royalist commander Lord George Stuart (1638), shouldering a crook against an Arcadian backdrop, to Cecil Beaton’s black and white photograph of a shadowed but beatific Mick Jagger, fingers tentatively arched as if in prayer (1967).

The Van Dyck self-portrait, in which he appears long-haired and imperious, every inch the Royalist courtier, and stares pityingly out at us over his shoulder, is a reminder that so often these men are dictating the terms on which they are appraised, either by commissioning portraits as status symbols, or cutting out the middle-man and painting themselves. They gaze out at us gazing at them.

Sir Anthony Van Dyck (c. 1640), Anthony Van Dyck. National Portrait Gallery, London