I have always been intrigued by Félix Vallotton (1865–1925) – by his strangeness, his acerbic wit, his offbeat colour, and his odd position outside the mainstream artistic currents of his time. This highly individual artist has never received the attention bestowed on his more famous ‘brethren’ in the Nabis group, Bonnard and Vuillard. Although Vallotton has always been admired in his native Switzerland – the majority of his works remain in Swiss museums and private collections – he has received scant recognition elsewhere. In Britain, apart from an exhibition of his prints put on by the Arts Council in 1976, there has never been a major show of his work.

So I was thrilled by the chance to stage an exhibition on this ‘very singular Vallotton’, as Thadée Natanson, co-founder of the avant-garde cultural journal La Revue blanche, described him in the early 1890s. On occasional trips to Switzerland, I had been captivated by his work on view at the Kunsthaus Zürich, the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne, and the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva. And for some years at the Royal Academy, we had talked about doing a Vallotton show; then a major retrospective held at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2013 was an opportunity to see many of his works together, and provided the spur we needed to think about making a show ourselves. Smaller and more focused than the Paris exhibition, it will be presented in the Sackler Wing of Galleries in June, and will travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in the autumn.

Self-portrait at the Age of Twenty (1885), Félix Vallotton. Photo: © Nora Rupp/Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne

The first step was to enlist the support of the Fondation Vallotton in Lausanne, the city of the artist’s birth. Marina Ducrey, long-time curator of the foundation, and her successor, Katia Poletti, devoted years to producing an exemplary, in-depth catalogue raisonné of Vallotton’s work. This provided the basis for our research for the exhibition. Their assistance in shaping the show and locating works in private collections has been invaluable.

Vallotton was an individualist from the beginning. He left behind his puritanical, Protestant upbringing in Lausanne when he set off for Paris at the age of 16. Arriving in the capital of art in 1882, he attended classes at the informal Académie Julian. The assurance of his Self-portrait at the Age of Twenty demonstrates his independence and his espousal of a tradition far removed from French Impressionism, the prevailing avant-garde style in Paris at the time, and one rooted in the cool, linear northern European realist tradition – that of Dürer and Holbein. Another striking early work, The Sick Girl (1892), reveals his allegiance to the Dutch masters of the 17th century. But his unique vision emerged in 1892 with a work of confounding originality: Bathing on a Summer Evening. This witty and stylish parody of a familiar Arcadian theme was greeted with ridicule when it appeared at the Salon des Indépendants the following year. Toulouse-Lautrec was one of the few to appreciate it, but even he expected the police to come and take it away. Clearly, Japanese ukiyo-e prints lie behind the flatness and linear sophistication of this large composition. And it was japonisme that Vallotton shared with artists in the Nabis (‘prophets’) group with whom he was associated in the 1890s (though even here he didn’t quite fit in; they called him le Nabi étranger). He adopted their decorative flattening of forms, high viewpoints and the informal technique of painting on cardboard (as in Street Scene in Paris, 1897).

Vallotton found his own voice too when he took up printmaking in 1891. It turned out to be a natural medium for him, especially woodcuts; it also brought him a necessary means of earning a living. Photomechanical techniques had led to an explosion in printing in the late 19th century, and there was a proliferation of publications of all kinds. Vallotton’s illustrations for the popular press, often of a left-wing bent, frequently record incidents of Parisian street life, the flâneur, and the psychology of the crowd.

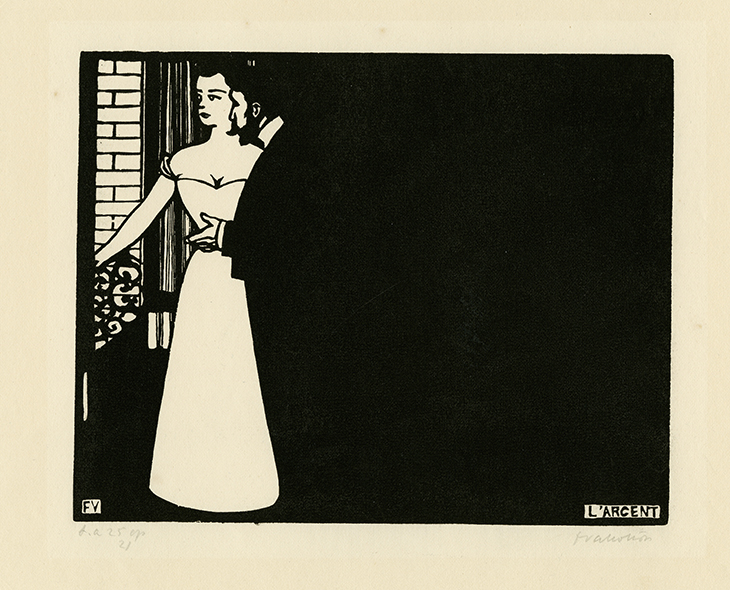

The late 1890s are generally considered the highpoint of Vallotton’s career, so it was important for us to include one of his great masterpieces from this period, Le Bon Marché (1898), which has not been exhibited for several decades, and never in Britain. This triptych – a format traditionally associated with religious art – presents a splendid panorama of Paris’s most famous department store. With its crowds of shoppers, brilliant lights and colourful stacked shelves, it is a witty critique of bourgeois consumerism. It was also in these years that Vallotton produced Intimités (1897– 98), the series of woodcuts on which much of his reputation rests today. In these vignettes the artist captures the intrigues of Parisian bourgeois society with a mordant wit. Couples trapped in domestic interiors cheat, lie and deceive in enigmatic scenarios in which it is never clear who is the victor and who the victim. The most daring of these is Money, in which Vallotton floods three-quarters of the plate with unmodulated black ink and highlights, against the white of the woman’s dress, the man’s outstretched hand that so piquantly encapsulates the transaction taking place.

Intimacies V: Money (1897/98), Félix Vallotton. Photo: © Musées d’Art et d’Histoire, Ville de Genève

In 1899, Vallotton’s life underwent a dramatic change when he turned his back on his bohemian Left-Bank life and married Gabrielle Rodrigues-Henriques, the daughter of one of Paris’s leading gallerists, Alexandre Bernheim. His entry into the Parisian beau monde brought about a marked change in his work as he adopted a distinctive hardedged, smooth realism that would persist for the rest of his career. Ingres was a talisman for Vallotton, especially in his paintings of the female nude.

His landscapes can assume an almost hallucinatory magnetism achieved through his method of paysage composé (composed landscapes), which he created in the studio, away from the motif, filtered through memory and imagination. The sunsets, for which he was celebrated, have an extraordinary, heightened intensity and often a radiant beauty, while other landscapes suggest mysterious, suppressed narratives and a lingering disquiet. Vallotton’s work has been compared to the New Objectivity movement in Weimar Germany, to the paintings of Edward Hopper and to the films of Alfred Hitchcock. Yet in the end, Vallotton remains an original, whose work continues to surprise and challenge.

‘Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 29 September.

From the June 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.