As a teenager, the artist Niki de Saint Phalle modelled for the leading fashion magazines of the day. Trussed up in furs and diamonds, her image on the covers of Vogue, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar and Life dominate the first room of the retrospective of her work currently at the Guggenheim Bilbao. Her huge grey eyes and slender figure were well suited to the fashion world of the late 1940s. Her mind was not. ‘I was lucky to encounter art,’ she said, ‘because I had, on psychological level, all it takes to become a terrorist.’

Sexually abused by her father at a young age, Saint Phalle had had a breakdown in 1953 and was hospitalised. She underwent electric shock therapy, and she discovered art. Her first works self-consciously mimicked the leading American artists of the day (Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg), integrating their style into her own mosaics of found objects, crockery fragments, plaster and paint.

Then it got angry. In 1960, the same year Saint Phalle left her husband and young children, she pinned a man’s shirt to a wooden panel with large, rusty nails, and gave it a target board face and a barbed title, Hors d’Oeuvre or Portrait of My Lover. In 1961 she picked up a rifle, and peppered bulbous, object-encrusted plaster sculptures with bullets, so that they bled paint all over their gold frames. These Shooting Paintings became increasingly theatrical, and Saint Phalle became the only woman to be included in the Nouveau Réalisme group that included the pioneering performance artists Arman, Christo, Yves Klein and Jean Tinguely.

Grand Shoot – J Gallery Session (Grand Tir – Séance galerie J) (1961), Niki de Saint Phalle © Niki Charitable Art Foudation, Santee, USA. Photo: © Laurent Condominas

Saint Phalle’s beauty was as much of a weapon as her shotgun and her paintbrush: over her lifetime she seduced the media as much as the trails of men she left in her wake. Contemporary films show this, and are integrated well throughout the exhibition. Initially they proclaim her to be a member of l’avant garde, showing her railing against the patriarchy or coolly taking aim at her sculptural targets. Later, we see her act and direct in her own highly disturbing feature film, Daddy (1972).

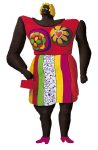

An appealing, psychedelic aesthetic twinned with darker, more serious critique is something that plays out continuously in the exhibition. It shows how the Nanas – the colourful, bulging female figures that Saint Phalle is perhaps best-known for – emerged in the mid 1960s from a curious blend of sculptures that incorporated the forms of fertility goddesses, women giving birth, and Kennedy and Khrushchev. Although easily interpreted as joyful, happy sculptures, the Nanas have a powerful intention as an amplification of femininity. ‘They are an army of women sent to take over the world’, as Saint Phalle’s granddaughter, Bloum Cardenas, put it.

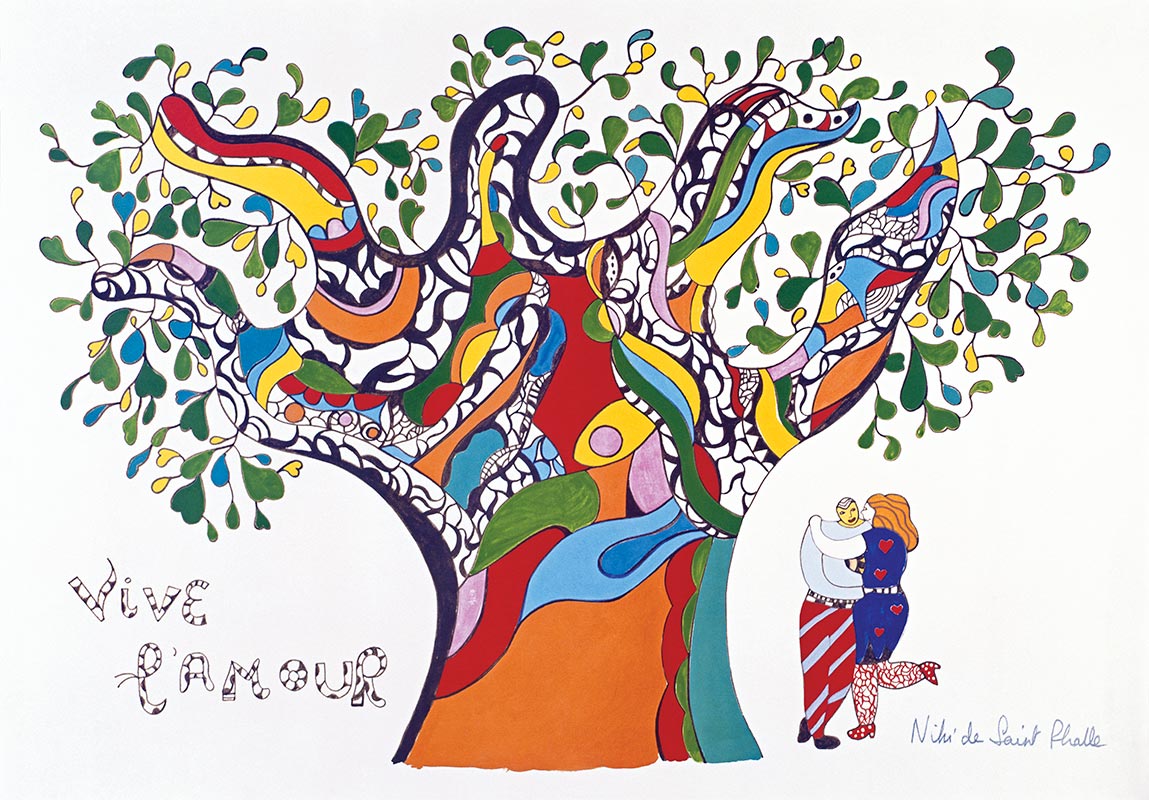

Saint Phalle’s silkscreen prints – humorous faux-naïve doodles that wouldn’t look out of place on Topshop merchandise – also use this quality to particularly compelling effect. Dreamy teenage sentences like, ‘Why don’t you love me? Have you looked at my face? I’m not so ugly and my friends find me very intelligent’ are curled around simple line drawings, coloured brightly with neon.

Long Live Love (Vive l’Amour) (1990), Niki de Saint Phalle © Niki Charitable Art Foudation, Santee, USA .Photo: © Ed Kessler

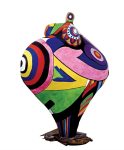

Although Saint Phalle’s feminist stance is most apparent from her work, she campaigned tirelessly for other causes, tackling issues such as violence in the media, gun control, AIDS, and even George W. Bush. Her commitment to public sculpture was a result of the belief that it could spread happiness, as well as being a way to reclaim male-dominated spaces. The final room of the show is dedicated to these large-scale projects, demonstrating in particular the ambition that lay behind the creation of her self-funded sculpture park, Tarot Garden, in Tuscany. It is a suitable ending to an exhibition that above all shows Saint Phalle as a force of nature, independently carving her own scenic path through personally and politically challenging landscapes.

‘Niki de Saint Phalle’ is at the Guggenheim Bilbao, until 11 June, 2015.

Related Articles

Inquiry: Wall Flowers – women in historical art collections (Lily Le Brun)

Stars in whose eyes? The lack of women artists in Bailey’s Stardust(Elizabeth Grant)

Women in art: Australia honours Julie Ewington and Fiona Foley (Tim Walsh)

More than ‘women artists’: Dorothea Tanning and Shelagh Wakely in London (Belinda Seppings)

Abstraction and Representation: women artists and contemporary art(Catherine Spencer)