Elain Harwood’s Space, Hope and Brutalism reviewed

From the December issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

On a ‘perfect autumn day’ in 1958, Anthony Wedgwood Benn MP visited a new 14-storey skyscraper of modern flats in Bristol. He saw the flats as the expression of the fruits of a project that merged modernism with politics: ‘To see the bright airy rooms with the superb view and to contrast them with the poky slum dwellings below […] was to get all the reward one wants from politics. For this grand conception of planning is what it is all about.’ In the years since, there have been several upheavals in the way we see and understand buildings of this period. For decades they were viscerally loathed for their perceived technical and social failings and aesthetic thuggery. More recently, they have been praised for their visual robustness and social idealism, qualities that are contrasted to the flimsy yet bullying symbols of crass commercialism, gentrification, and rampant capitalism prevalent today.

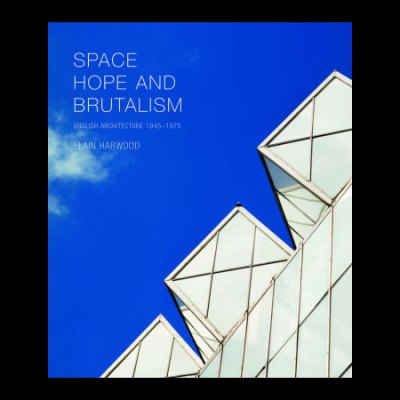

Elain Harwood’s magisterial Space, Hope, and Brutalism offers us a chance to recapture some of the excitement Benn felt during modernism’s high noon. It also allows us to reconnect this architecture with the social projects of which it was a central part. The book is enormous and comprehensive, mirroring some of the megastructural scale and bloody-minded ambition of its subject. Harwood gives us a dense and authoritative tour of the entirety of English architecture from 1945 to 1975. The book has been in gestation for 20 years, and the result is an epic of architectural history, produced with an unwieldy luxuriousness notable even for Yale University Press.

Not everyone will have the stamina to read the book cover-to-cover; but doing so gives one a remarkable panorama of buildings. The result does not function as an apologia, and Harwood does not attempt to overturn common misgivings about the gimcrack quality and unsustainable nature of much construction, the intimate link between modernism and the despoliation of historic towns and city centres, or the faceless and top-down nature of many state projects. What does powerfully emerge though, is a generation displaying a remarkable fecundity of architectural talent, comparable to other eruptions in English architectural culture such as the English baroque or the mid-Victorian Gothic Revival. The buildings we discover here blow apart any idea that this was solely an architecture of monotonous galumphing boxes. There is an abundance of sheer beauty on show, ranging in tone from attenuated delicacy to sublime romanticism, and also covering a remarkable spectrum of styles and approaches. James O. Davies’s colour photography unashamedly aestheticises these buildings, showing them proud and stark against crisp blue skies or glowing from inner light at dusk.

The fact that these remarkable qualities were achieved, in so many cases, for public purposes and under the strictures of penny-pinching rather than through the largesse of a great patron makes their achievement more impressive. Having said that, one of the most revelatory chapters is on private houses – where we see the period’s various styles at their most glamorous.

Choir and sanctuary, Cathedral Church of St Michael and All Angels, Coventry, scheme won in competition by Basil Spence in 1951; built in 1955–62 Photo: James O. Davies; © Historic England

If the book’s organisation, based around chapters on building typologies, means that we miss some of the narrative trajectory of previous histories of the subject by Lionel Esher or Alan Powers, then we also gain a lot. Harwood can sidestep the polemical, overarching arguments that tend to bog down this subject, approaching buildings on their own merits, rather than as a proxy for something else – whether it is social failure or the past glories of the welfare state. The inclusive approach has the added benefit of not allowing the period’s thumpers, such as Alison and Peter Smithson, or James Stirling, to dominate proceedings or drown out more subtle or unusual voices, such as McMorran and Whitby, who continued to practise a classicism free from fustiness, or Powell and Moya, whose modernism combined wit and grace. The word ‘brutalism’ in the title is misleading, as there are a multitude of styles on display here. This is unfortunate, as the stylistic eclecticism of the period is such an eye-opening aspect of the book. The book’s emergence out of Historic England (Harwood is the organisation’s Senior Architectural Investigator) means that Harwood ignores the rest of Britain, but the limitation appears rather arbitrary. It also means that we miss the glorious churches of the heroic Glaswegian firm Gillespie, Kidd and Coia.

Stockwell Bus Garage, by Adie, Button & Partners, 1951–53; John Smith of A.E. Beer & Co. Photo: James O. Davies; © Historic England

The book is nicely balanced between self-conscious Architecture with a capital ‘A’ and more everyday modernisms. So, alongside accounts of landmarks like the menagerie of brutalist hulks on the Southbank, the urbane gigantism of the Barbican, and Basil Spence’s elegant Coventry Cathedral, we get other stories: from the humble and humane modernism typified by the Hertfordshire schools, to the sexy yet slapdash modernism of shopping centres and office blocks.

Today we seem intent on effacing the remains of the post-war period with the same philistine zeal with which the post-war generation set about destroying the Victorian city. The victories against this tide are well documented in a new edition of Harwood’s excellent England’s Post-War Listed Buildings – reissued by Batsford to coincide with Space, Hope, and Brutalism. But the defeats continue to be considerable – and go far beyond those making the press, such as Birmingham Central Library and Robin Hood Gardens. History will see Harwood’s book as analogous to the 1960s attempts at a refashioning of opinion found in books like Asa Briggs’ Victorian Cities. A more generous judgement of this architecture is inevitable, part of the natural cycle of taste, but the longer it takes to achieve widespread acceptance the more we will have lost. Buy this book, join the Twentieth Century Society, and learn to appreciate our built inheritance from an extraordinary time in British history – you don’t have to subscribe to wholesale arguments about the successes or failures of the period to understand and value its rich remains.

Space, Hope, and Brutalism by Elain Harwood is published by Yale University Press (£50).