In this ongoing series, Apollo previews a range of international exhibitions, asking curators to reveal their personal highlights and curatorial impulses. Kristen Collins and Jeffrey Weaver are the curators of ‘Canterbury and St Albans: Treasures from Church and Cloister’ at the J. Paul Getty Museum

Tell us a bit about the exhibition…

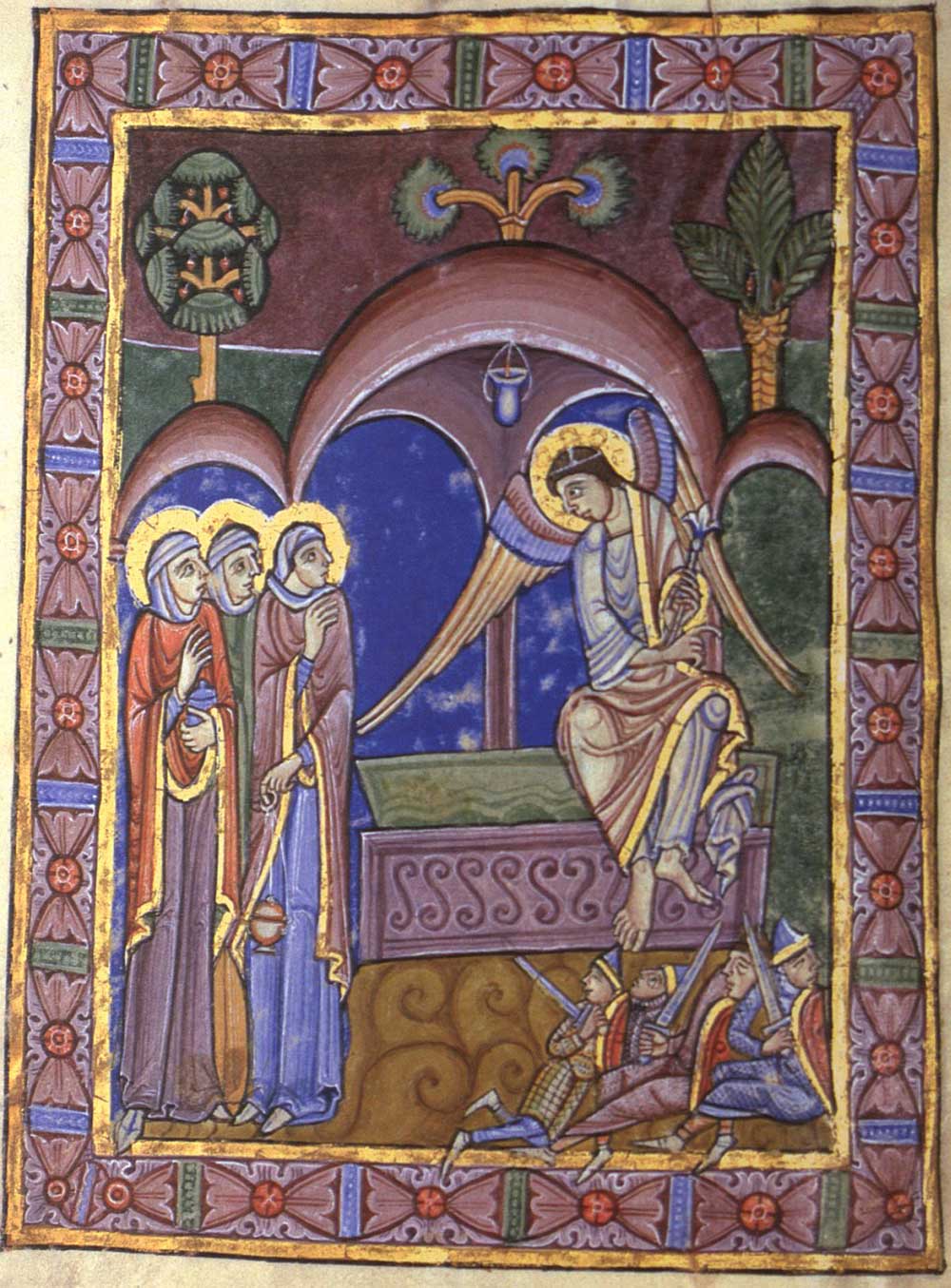

This exhibition brings together two great representations of English Romanesque art; monumental panels of stained glass from Canterbury cathedral, and the St Albans Psalter, an elaborately illuminated manuscript now in the collection of the Cathedral Library in Hildesheim, Germany. Through the juxtaposition of monumental and miniature painting, the show aims to explore issues of audience and experience – essentially how medieval people saw and ‘read’ pictures in a variety of contexts.

What makes this a distinctive show?

It’s very rare to walk into a museum in the United States and to be able to view monumental painting from the medieval era. With the loan of the stained glass windows of the Ancestors of Christ from Canterbury cathedral, southern Californian museum-goers will be offered a truly immersive experience.

How did you come to curate this exhibition?

Working independently on separate exhibition ideas for the glass and the Psalter, we became aware of each other’s work, and thought this presented a unique opportunity to bring the two together for a display that demonstrates the scope of English Romanesque painting.

What is likely to be the highlight of the exhibition?

The majority of visitors will undoubtedly be dazzled by the grand scale and masterful painting of the windows – we have been able to reconstitute one full lancet window from the choir clerestory at Canterbury, restoring it to its original format for the first time in over 200 years. But for medievalists it may be the St Albans Psalter, which is one of the most lavishly illustrated manuscripts of 12th-century England, and perhaps the most famous. For conservation reasons, the handling of such manuscripts is restricted, so it’s quite rare even for specialists to have the opportunity to study the pages of such an object for an extended period of time.

And what’s been the most exciting personal discovery for you?

(Kristen Collins) Our team found tiny pinpricks through the painted eyes of demons and tormenters of Christ in the Psalter’s illuminations. One of my research interests is devotional iconoclasm and this provided an excellent example of the powerful reaction that medieval viewers had to pictures.

What’s the greatest challenge you’ve faced in preparing this exhibition?

Knitting together two distinctly different media in one exhibition was initially daunting, but once we realised that our story was one of oppositions – monumental and miniature, communal and private devotion, static and haptic – the organisation of the exhibition coalesced for us.

How are you using the gallery space? What challenges will the hang/installation pose?

We really wanted to emphasise the difference between an architectural art that was viewed from a distance and a medium intended to be held in your hands. Our team designed and built special lectern-like stands for the framed Psalter leaves. We also mounted the glass panels in a manner similar to their original arrangement, with two figures stacked one on top of the other and surrounded by a decorative border.

Which other works would you have liked to have included?

(Jeffrey Weaver) The glass representing the biblical figure Methuselah. The artist who painted it and other early works at Canterbury is referred to as the ‘Methuselah Master’ and as such, it is too important a piece ever to be permitted to leave the cathedral.

‘Canterbury and St Albans: Treasures from Church and Cloister’ is at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center from 20 September 2013–2 February 2014.