In this ongoing series, Apollo previews a range of international exhibitions, asking curators to reveal their personal highlights and curatorial impulses. Daniel F. Herrmann is the Eisler Curator and Head of Curatorial Studies at the Whitechapel Gallery, and one of the curators of the exhibition.

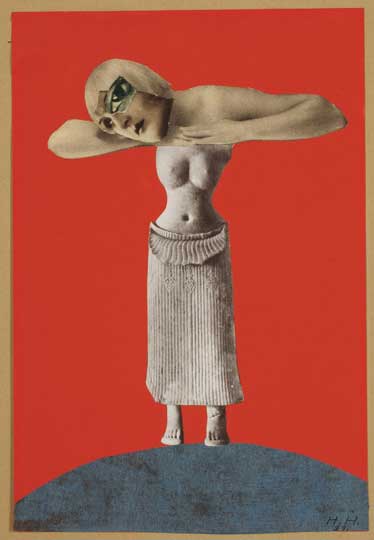

Untitled (From an Ethnographic Museum) (1930), Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg. Photo: Maria Thrun

Can you tell us a bit about the exhibition?

The Whitechapel Gallery will show the first major UK exhibition of the German artist Hannah Höch. Hannah Höch was an important member of the Berlin Dada movement and a driving force in the development of 20th-century collage. Splicing together images taken from fashion magazines and illustrated journals, she created a humorous and moving commentary on society during a time of tremendous social change.

What makes this a distinctive show?

The exhibition brings together over 100 works from major international collections. Works by Hannah Höch are fragile and rarely travel, so this will really be a once in a lifetime chance to see these works in London.

How did you come to curate this exhibition?

I have always greatly admired Höch’s work, her rebellious spirit and her sense of humour. Her use of images from the mass media and popular culture has never seemed more relevant. It felt like a major survey of her work in the UK was very much due. From highlights of her early Dada collages through to the colourful lyrical abstraction of her later years, we will show over six decades of Höch’s acerbic and poignant works.

What is likely to be the highlight of the exhibition?

Alongside some of Höch’s most celebrated works such as Staatshäupter (Heads of State) (1918–20), Hochfinanz (High Finance) (1923) and Flucht (Flight) (1931), I think one of the highlights will be seeing a selection of her works from the famous series From an Ethnographic Museum. The remarkable collages, which combine images of female bodies with masks, sculptures and artefacts are complex and visually striking. We will be showing a work from the series lent by the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, the only work by Höch in a public UK collection, and bringing it together with works from a wide range of lenders including MoMA, New York and the Centre Pompidou, Paris.

And what’s been the most exciting personal discovery for you?

I am amazed and delighted by the amount of interest we are already getting from visitors, artists, and students. Höch’s witty and beautiful works pack a real punch and her collages are truly inspiring to contemporary generations.

What’s the greatest challenge you’ve faced in preparing this exhibition?

Höch’s body of work is rich and varied; we wanted to select works which best represent the whole breadth of her career. She is often seen purely in the context of Dada, so we were keen to explore the full range and development of her practice.

How are you using the gallery space? What challenges will the hang/installation pose?

We are busy working on the spaces now, constructing new walls and creating a beautiful display for these fragile and important works. The exhibition will be hung chronologically, so visitors are taken on a journey through her career from her early training and the tumultuous years of the Weimar Republic all the way to her fantastic works of the post-war period.

Which other works would you have liked to have included?

We are delighted to have been able to bring together so many works from public and private collections all over the world. The exhibition has received a tremendous amount of support from international colleagues, scholars and lenders, which is enabling us to show an extensive overview of her work. The exhibition and its catalogue will really give visitors an insight into why she remains such an inspiring figure to so many people today.

‘Hannah Höch’ is at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, from 15 January–23 March.

Related Articles

Well Cut: Hannah Höch at the Whitechapel Gallery (Beatrice Schulz)