A new exhibition at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum looks at the significance of drawing to Italian Renaissance sculptors – a fascinating but under-explored field. How did their works on paper relate to their three-dimensional models, and to finished works? We spoke to Michael Cole about the exhibition, its inspiration, and where it might lead.

Click here for a gallery of highlights from the exhibition

Can you tell us a bit about the exhibition?

We have a perennial interest in how artists worked: what happened in the workshop or the studio, what the making of things entailed. All Italian Renaissance sculptors produced models, and a series of great exhibitions has resulted in an excellent and growing literature on the examples that survive. But there has been surprisingly little comparative study of sculptors’ drawings, of when sculptors turned to paper and why. What makes the topic especially intriguing is that some sculptors – Baccio Bandinelli and Guglielmo della Porta, for example – left hundreds of drawings, whereas others left few or none at all.

What makes this a distinctive show?

Well, for one thing, it features infrequently seen works by many of the best sculptors of the Renaissance: most visitors to the exhibition will know the major artists it features but not the objects on display. We’re also allowing direct comparison of related works that normally live in distant places: two portions of what was once a single sheet by Jacopo della Quercia; four studies by Michelangelo of an ancient Venus along with a terracotta he derived from the same work; two sculptures by Cellini and the drawings made for or after them; two sequences of drawings by Bandinelli. Visitors will get to see the wide spectrum of ways that sculptors used drawings.

How did you come to curate this exhibition?

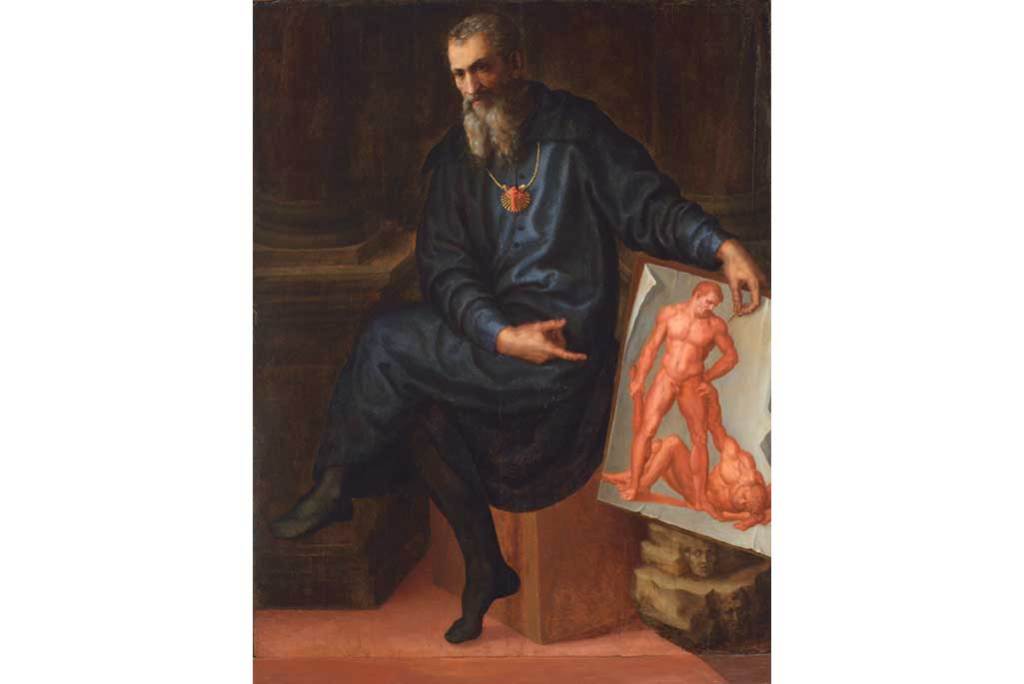

Oliver Tostmann, then a curator at the Gardner, invited me to collaborate with him on a show around the museum’s great painted portrait of Baccio Bandinelli. I proposed that rather than doing something monographic, we try to put together an exhibition that provided a context for thinking about what Bandinelli is doing in that painting – displaying a (probably fictive) drawing.

What is likely to be the highlight of the exhibition?

There are so many great things. I suppose the two works that I currently find most fascinating are the drawing in Rennes that has been ascribed to Donatello and the drawing in the Morgan that has been given to Leone Leoni. If these attributions are correct – both have been doubted, but I myself have come to accept both – they count among the only known drawings by those sculptors, and they become the reference points for reconstructing a larger oeuvre.

And what’s been the most exciting personal discovery for you?

That there is so much more work to do! While I hope the exhibition and the catalogue make a substantial contribution to the study both of drawing and of sculpture, my visits to drawing collections and my conversations with many colleagues have made me realise that I could happily continue with this topic for decades to come.

What’s the greatest challenge you’ve faced in preparing this exhibition?

Sculptors’ drawings often look quite different from their works in three dimensions, and a single sculptor’s drawings can vary dramatically in style and subject matter. Drawings are ambiguously documented, many sculptors had painters supply them with drawings, and artists of all kinds made drawings after distinguished sculptures. For these and other reasons, questions of authorship surround nearly every artist in the exhibition. I’ve never previously worked on a project where this was such an omnipresent question.

Which other works would you have liked to have included?

My biggest regret is that we do not have a work by Ghiberti – I would have loved to include the Albertina’s Flagellation. And it would have been wonderful to look again at the drawings attributed to Nanni di Banco and to Desiderio da Settignano in the context of this gathering of works. But we are at the limits of both our budget and our wall space, so adding anything would have required us to give up something else, and I don’t know what I would have been willing to sacrifice.

‘Donatello, Michelangelo, Cellini: Sculptors’ Drawings from Renaissance Italy’ is at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum from 23 October–19 January 2015.