In 16th-century Tlatelolco, today part of Mexico City, a Spanish cleric and a small group of Indigenous elders, authors and artists created a manuscript documenting their rapidly changing world. As plague ravaged the population, these scholars, scribes and painters composed a document illustrated with some 2,500 images – what has been described as the first encyclopedia in the Americas. The manuscript, known as the Florentine Codex, documented Mexica culture and the Aztec Empire in brilliant detail, as well as the devastation that followed the Spanish invasion of Mexico in 1519, including the introduction of diseases to which the native population had little resistance.

The impetus for the project was practical: as part of their evangelization campaigns, Spanish mendicant friars needed to know the beliefs and traditions of the Nahua-speaking communities they hoped to convert to Catholicism. In the 1570s, the Franciscan friar Bernadino de Sahagún, in collaboration with a group of Nahua speakers including Antonio Valeriano, Alonso Vegerano, Martín Jacobita, Pedro de San Buenaventura, Diego de Grado, Bonifacio Maximiliano, Mateo Severino and others whose names are unknown to us created something far more expansive.

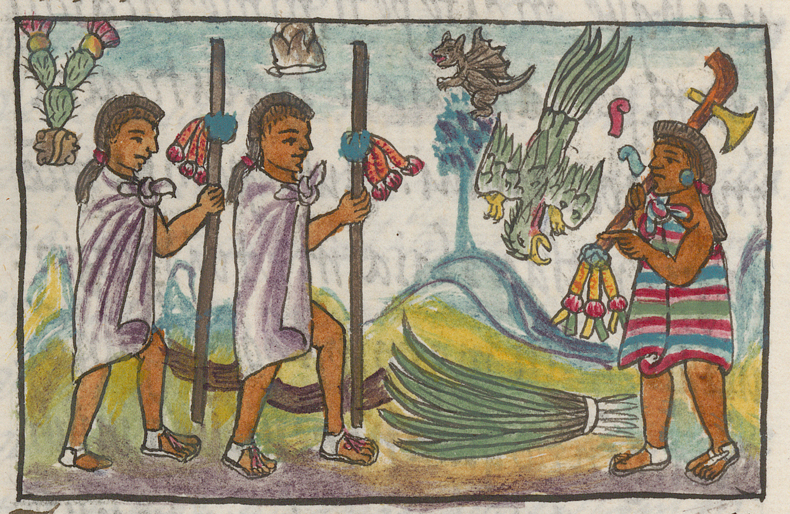

The Tlatelolcan warrior Tzilcatzin throwing stones at the invading Spaniards in Book 12 of the Florentine Codex (1577), Alonso Vegerano. Photo: courtesy the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, and MiBACT

Following the model of European encyclopedias, especially Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, the codex is composed of twelve books with parallel texts in Nahuatl and Spanish recording the gods, ritual calendar, natural history, philosophy and other subjects of New Spain, including the events of the invasion itself. The manuscript, known as the Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España (The Universal History of the Things of New Spain), resides in the Laurentian Library in Florence, but it is the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles that has unlocked the wonders of this remarkable work. The newly unveiled Digital Florentine Codex reveals the magisterial scope of the endeavour. With a user-friendly interface, trilingual texts (Spanish, Nahuatl and English) and superb, high-resolution images, a reader can search for specific topics with ease.

Feather worker (amantecatl) in Book Nine of the Florentine Codex (1577), Alonso Vegerano. Photo: courtesy the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, and MiBACT

A reader could, for example, search for ‘feather’ and discover in Book Nine the secrets of the amantecah, the artists skilled in feather-working – one of the most highly esteemed art forms in the Aztec Empire. One could learn which birds might have the appropriate plumage – grackle feathers were good for outlines, apparently – but also read, in great detail, how the feathers would be gathered and bound, sometimes affixed to a backing with an adhesive made from orchid bulbs. Iridescent feathers from hummingbirds, quetzals, roseate spoonbills and blue cotingas would be carefully placed so they ‘glowed and shimmered,’ in the resplendent finery donned by kings, warriors and priests.

A xicalpapalotl butterfly in Book 11 of the Florentine Codex (detail; 1577), Alonso Vegerano. Photo: courtesy of the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, and MiBACT

European pigments were used to depict European subjects, while locally-sourced materials were reserved for subjects from the pre-Conquest period, as was revealed in a study by project co-head Diana Magaloni. Despite such important studies taking place over the past half century, the manuscript has remained unavailable to the public and often available only in partial form to scholars. The daunting size of the manuscript itself impeded a broader circulation of the work. The Digital Florentine Codex, a project helmed by Kim Richter and managed by Alicia Maria Houtrouw at the Getty Research Institute, has been enriched by the contributions of international scholars, including co-project directors Kevin Terraciano from UCLA and Jeanette Favrot Peterson from UCSB, linguists from the Instituto de Docencia e Investigación Etnológica de Zacatecas in Mexico, and a large team of specialists. The Digital Florentine Codex team has made this important manuscript not only accessible but inviting. The reader in search of one subject cannot help but stumble upon a fascinating description of another: merchants, for example, tried not to call attention to themselves, walking about ‘wearing only their miserable maguey fiber capes,’ or that men who were distinguished by their bravery were allowed to wear lip plugs. It is a project that rewards getting lost.

Merchants acquiring quetzal feathers in Book Nine of the Florentine Codex (detail; 1577), Alonso Vegerano. Photo: courtesy the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, and MiBACT

The Digital Florentine Codex also underscores the complexities of translation in a broader sense, not just the evident and impressive labour behind the Getty Research Institute’s initiative, but how ideas are transmitted (or not) and transformed. The side-by-side translations (which include the first English translation of the Spanish text, by León García Garagarza) encourage us to go from one to the other – an exercise that reveals distinct interests and understandings. From Nahuatl to Spanish a reader can see how concepts are elided or softened; the translations of Nahuatl to English bring back some of the rich texture of Mexica worldviews, whereas the English translation of Spanish text reveals frequent ‘code-switching’ and the use of Nahuatl words, many of which have made their way into modern Spanish. The prologue to Book Two of the Florentine Codex notes that the manuscript ‘has been examined and revised by many, and for many years, and much effort and many misfortunes have been endured in order to render it in the state in which it is now found.’

It is unquestionably cause for celebration that, thanks to the Digital Florentine Codex project, this wondrous window has been opened on to otherwise unattainable information, both in text and illustration, that offers new paths to enrich scholars and the broader public.

View the Digital Florentine Codex: florentinecodex.getty.edu