It seems that Florine Stettheimer was a woman forever in good company, from her female-centric family life to the creative salons she hosted for like-minded contemporaries, including Marcel Duchamp and Georgia O’Keeffe. In the late 1920s, Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson approached her to design costumes and sets for their avant-garde opera Four Saints in Three Acts. First performed in 1934, it was a production so untethered to operatic tradition that it prompted a friend of Stein to write to her saying: ‘It will finish opera, just as Picasso has finished oil painting.’ It didn’t, of course, enjoying popular runs on Broadway and in Chicago. The names Duchamp, O’Keeffe, Stein, and Thomson are ingrained in the cultural imaginary of this legendary era, but what of Stettheimer?

A documented excerpt of Four Saints plays in the central chamber of ‘Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry’, a retrospective first held at New York’s Jewish Museum, and now at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto for Stettheimer’s Canadian debut, bringing fresh eyes to the works of this fascinating artist, poet, and designer. That Stettheimer didn’t gain the same popular legacy as her peers was in part an act of self-sabotage. After a solo exhibition in New York in 1916 failed to sell a single piece, she resolved never to show publicly again, presenting her works only to a close circle of friends and family.

Family Portrait, II (1933), Florine Stettheimer. Image: © The Museum of Modern Art, New York

This pull between public and private space is apparent throughout the three sections across which this exhibition is staged (named ‘Acts’ in an echo of Thomson and Stein’s opera). Act One opens on family life, and the many portraits that Stettheimer made of her sisters Carrie and Ettie, her mother, and herself. Family Portrait, II (which Stettheimer considered her master work) of 1933 is particularly enchanting. Stettheimer conjures a dream-like scene, the traditions of a languid salon portrait surreally opening up into an open blue expanse above. Iconic New York monuments grace this sky (or sea), alongside free-floating chandeliers and decorative plaster mouldings rendered in puffy dollops of paint. Large open-bloom flowers dominate the foreground, under which a star-motif floor is emblazoned with the names of the Stettheimer clan. In other works in the exhibition’s first Act, further influential women – Stettheimer’s aunt, and her Stuttgart art teacher – appear, emphasising the dominance of female company in her life.

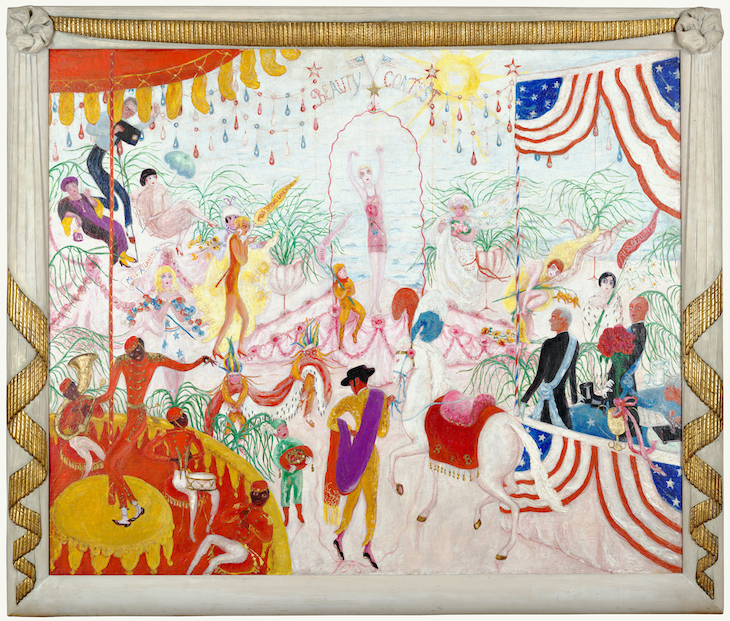

Beauty Contest: To the Memory of P.T. Barnum (1924), Florine Stettheimer. Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut

It’s not until Act Two that any male presence is introduced, and then accompanied by witty barbs. In her portrait of critic Henry McBride, Stettheimer positions him as a tennis umpire, with stick figures playing matches at his feet, a nod to his reputation as a tastemaker. In another portrait, American artist Louis Bouché is surrounded by lovingly painted lace, a material that he loathed and saw as the epitome of Victorian bad taste, but that Stettheimer adored. Act Three offers further glimpses of Stettheimer’s sense of humour. A frenzied shopping scene in a department store is signed by way of a Pekinese Dog wearing a monogrammed ‘F.S.’ sweater, while an all-American beauty contest is staged (and titled) after a P.T Barnum circus.

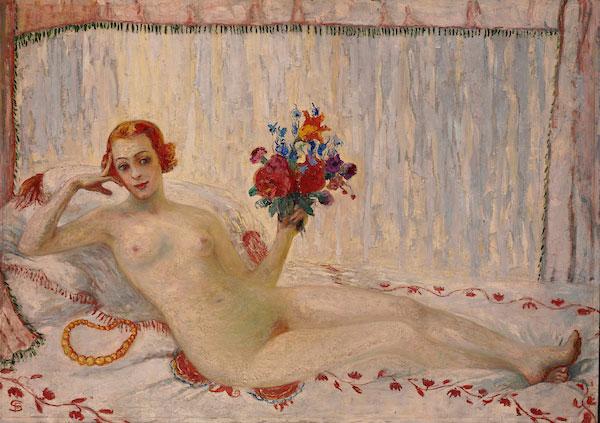

A Model (Nude Self-Portrait) (1915), Florine Stettheimer. Art Properties, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

A genuine sense of leisurely enjoyment emanates from Stettheimer’s work. It’s true that she painted from a place of privilege, but she never shied away from this, rendering her world joyously while unafraid to lampoon its socialite circles. Her favouring of a ‘high camp’ style is mirrored in the design of the exhibition: an homage to art deco, with dusky pink and gold walls, title fonts in ornamental cursive and a central salon complete with chandelier and iridescent wallpaper. Perhaps Stettheimer would have approved, but I can’t help feeling that the Jazz Age adornment situates her art too firmly in that past era, rather than allowing it to be considered in a more contemporary context. Less visually beguiling paintings might have been overpowered by this heavily stylised presentation, but Stettheimer’s works can more than stand up for themselves. As the resplendent nude self-portrait that closes the exhibition attests, confidence and style were something that Stettheimer had in spades.

‘Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry’ is at the Art Gallery of Ontario, until 28 January 2018.