From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Georges Bemberg’s family knew that he collected art but exactly what and how extensively was a mystery. As one relative recalled, he might simply mention at dinner, ‘Ah, I passed an antiques shop just now, I saw a very pretty bronze,’ but offer no further details. What he didn’t say was that that the statuette might have been Rodin’s The Age of Bronze or a 16th-century piece of The Blind Orion Guided by Cedalion by Barthélemy Prieur and that he had taken it home with him. What he never said was, ‘Ah, I’ve bought a Titian or a Cranach,’ even though that is exactly what he did.

Bemberg (1915–2011) was born into a German family that had moved to Argentina in the mid 19th century and made money first in brewing, with Quilmes beer, before diversifying into banking, among other things. He was brought up in Buenos Aires but also spent much of his childhood in Paris. As an adult he had homes in Argentina, New York and Paris, and they needed filling, which perhaps helps explain why there is no clear rationale to his collection: he bought what appealed to him.

He was, by all accounts, a discreet collector. He didn’t buy through an agent and would bid anonymously at auctions. It allowed him a degree of privacy he clearly relished. As his collection grew he dispersed it through his various homes and no one – family or dealers – realised just what it contained.

The Age of Bronze (1876–77), Auguste Rodin. Fondation Bemberg, Toulouse. Photo: Jean-Jacques Ader

His connoisseurship was just one expression of broad cultural tastes. Bemberg studied comparative literature at Harvard and became an accomplished author, writing seven novels and collections of short stories, as well as essays, poetry and plays – some of which were performed in London and off Broadway. (He wrote his plays in English and his verse in French.) His cousin was the writer, publisher and literary hostess Victoria Ocampo, whose guests included such luminaries as Igor Stravinsky, André Malraux, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and Graham Greene. Bemberg’s own writer friends included Ortega y Gasset and Jorge Luis Borges. He was also an extremely accomplished pianist who studied under the composer and pioneering conductor Nadia Boulanger.

Bemberg’s first acquisition was a gouache by Pissarro, bought at the age of 20 in New York, and he never stopped. His collection, an eclectic gathering, eventually numbered more than 1,000 works spanning five centuries, from the late 15th century to the Second World War. Bemberg never married and long before he died he set about ensuring that his pieces could be seen by the public. In 1993 he established the Fondation Bemberg.

Although Bemberg had no links with Toulouse, the then mayor heard about a collection in search of a home – ‘Chinese whispers,’ as the Fondation’s current director Ana Debenedetti puts it to me – and offered up the magnificent Renaissance Hôtel d’Assézat in the old part of the city.

It was, says Debenedetti, ‘fate… it was meant to be’. When he first saw the building, Bemberg was besotted – ‘In a few seconds, my decision was made,’ he recalled; ‘it’s that or nothing’ – and became even more so when he learnt that the celebrated Argentinian tango singer Carlos Gardel, nicknamed ‘The Song Thrush’, was born in Toulouse. The doors opened in 1995, at which point visitors could see some of the collection in its new home. Upon Bemberg’s death in 2011, while various pieces went to family members, the majority were given to the foundation.

Bemberg had been greatly influenced by the Wallace Collection in London and his own acquisitions – though they were fewer and not of the same consistently high quality – were initially displayed in a similar way, as an attractive but not necessarily chronological mixture of paintings, bronzes, furniture and objets. The walls were lined with silk damask in assorted shades and the pictures were often hung stacked on top of each other. It was an aficionados’ display, handsome and nodding to the stateliness of the building, but one that suited the older works rather better than the 19th- and 20th-century pieces. So, in 2020, it was decided that the galleries should be revamped.

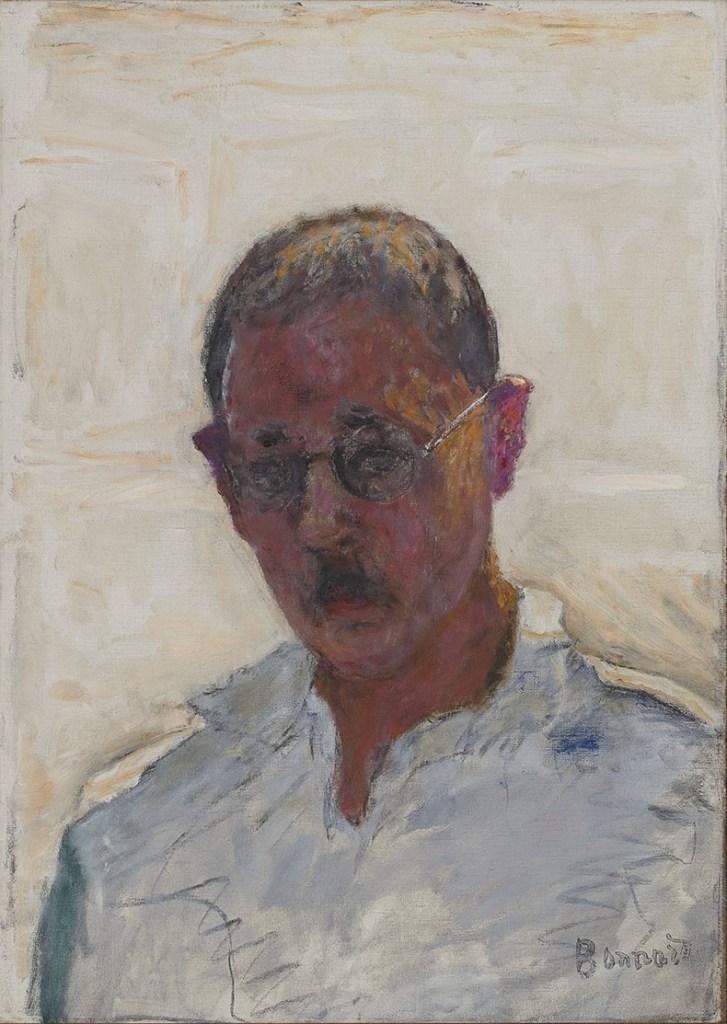

Self-Portrait on White Background, Open-Collar Shirt (1933), Pierre Bonnard. Fondation Bemberg, Toulouse

Covid initially stymied the implementation of the plan and shortages of materials meant that work didn’t start in earnest until 2021. Then, in the summer of 2022, Debenedetti took over as director of the Fondation Bemberg. A Parisian by birth, from 2009–21 she was curator of prints and drawings at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where she was responsible for two highly acclaimed exhibitions: ‘Constable: the Making of a Master’ (2015) and, true to her roots as a Renaissance scholar (her PhD thesis discussed the relationship between the birth of art theory and the philosophy of Marsilio Ficino in 15th-century Florence), ‘Botticelli Reimagined’ (2016).

At the Fondation Bemberg she found herself in a sympathetic institution. Bemberg had left no set-in-stone directions as to the integrity of the collection – no Richard Wallace-style diktat about never lending, for example – but rather encouraged its future custodians to show it as they thought best. Debenedetti wanted to bring some V&A influence, to ‘try to make sense of the collection and tell a story’. Along the way she hoped that this would reveal ‘something of the personality of the collector’. She thought that the original hanging was ‘too dense’ and decided to display fewer works: ‘I wanted to make the public look and I wanted to make it appealing, so people come back.’

Now, after a closure of three years and a renewal costing €6 million, financed by the foundation’s trust, the Hôtel d’Assézat has reopened. It is, says Debenedetti, an auspicious moment. The main fine art museum in the city, the Musée des Augustins, closed in early 2019 and is not now due to reopen until at least 2025, ‘so we have an opportunity – there is a bit of a gap in Toulouse’s cultural life and we are unique in the city.’ As a result, there is ‘huge expectation’ around the Fondation’s reopening.

The building itself is a significant asset. While the Musée des Augustins is a heavy and imposing structure, the Hôtel d’Assézat is a confection constructed from local rose-tinted stone and brick. A facade that spans two sides of the courtyard is decorated with paired columns that run through the classical orders as they ascend three storeys, windows inset within blind arches and blank stone roundels, with the whole ensemble topped by a 26-metre-high tower, the tallest in the city. Construction began on the building in 1555 to the designs of Nicolas Bachelier for a wealthy woad merchant named Pierre d’Assézat. It represents an exceptionally well-preserved and important early example of Italian Renaissance architecture adapted for France, complete with a grand rusticated entrance gate, a loggia and an external bridge. The tower itself is home to the Fondation’s bees – ‘they feed at a local flower shop,’ says Debenedetti, and their honey is sold in the gift shop. ‘We had bees at the V&A, but the honey was only for staff.’

The shop itself is a new addition, as are three rooms on the ground floor and basement set aside for temporary exhibitions and lectures. Upstairs, the two main floors have been given over to a chronological and thematic presentation: the Old Masters occupy one floor, the Moderns the other. Some partitions have gone, windows have been revealed and the silk wall coverings have been replaced by paint in various hues. The colour choices were Debenedetti’s and a mixture of aesthetics and whim: ‘There is a lot of coffee and chocolate drinking in Impressionist paintings so we chose a rich brown for their rooms,’ she explains.

Because the building was never Bemberg’s home, and indeed hadn’t been properly lived in for a century, it is perhaps no surprise that the display rooms are clearly gallery spaces rather than domestic interiors. So while the new hanging brings a coherence to the collection, the man who assembled them nevertheless remains a strangely nebulous presence.

Bemberg was particularly fond of Venice so the display starts with a selection of works by major figures from the republic – a portrait after Titian of a four-square Alfonso I d’Este from the end of the 16th century, and paintings by Tintoretto, Lorenzo Lotto and Jacopo Bassano. Overshadowing them is the Fondation’s signature work, an imposing single-figure Veronese, The Falconer (c. 1560), showing a huntsman stepping through a doorway, a bird on his wrist, a dog at his heel.

The Falconer (c. 1560), Paolo Veronese. Fondation Bemberg, Toulouse. Photo: Mathieu Rabeau; © RMN-Grand Palais (Fondation Bemberg)

It is a painting of great physical presence and intent. The circumstances of the commission are unknown but Debenedetti thinks that it may have been designed as part of a decorative scheme for a villa on the Terraferma, like the works that Veronese painted for Palladio’s Villa Barbaro.

In places, the personal nature of Bemberg’s collection can be felt. He was drawn to both Jan van Goyen’s View of the Port of Nijmegen (1648) and Hubert Robert’s classical ruins; to Pieter de Hooch’s decorous Interior with an Elegant Couple Playing Music (c. 1673–75) and a riotous inn scene combining violence, lust and gluttony by Pieter Brueghel the Younger; to Francesco Guardi’s flickering depiction of the Punta della Dogana (c. 1765) and Lucas Cranach the Elder’s humorous moral message The Ill-Matched Lovers (c. 1530). Similar variety is on show among his 19th- and 20th-century painters, ranging from Pissarro and Sisley to Signac and Sérusier, and Fantin-Latour and Odilon Redon to Gauguin and Raoul Dufy.

Portraits are a recurring presence throughout the collection. Bemberg, who said little about his paintings, thought that together they represented an ‘ideal’ family. They certainly make for a varied one. There is, for example, a recently cleaned picture of Louise de Savoie (c. 1530–40) attributed to Jean Clouet. When the black background was removed in preparation for the reopening, conservators found her sitting not in a darkened room but against a vivid teal background: it is the only known painted portrait of Francis I’s mother. Opposite her is a powerful portrait of an unknown man, possibly a doctor (there is a child’s skeleton on the table at which he sits) by Pietro Paolini. He has large, widely spaced eyes, a pronounced nose and chin and, painted in strong chiaroscuro, he turns to the viewer as if to reinforce his physicality.

Elsewhere, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s playful Portrait of Countess Kagenek as Flora (1792) stares across to Van Dyck’s restrained, near-monochrome depiction of Lady Dorothy Dacre (c. 1638–40); there is Monet’s unaffectedly intimate painting of his son Jean in a pompom bonnet (1869) and Berthe Morisot’s fluttering pastel A Young Girl Reading (1886). In a different register altogether, Pierre Bonnard’s last and deeply strange self-portrait, painted in 1945, two years before his death, shows the painter blank-eyed and mask-like with Japanese overtones.

Indeed, the Bonnard is part of two collections-within-the-collection. Bemberg was an admirer of Walter Sickert and purchased 10 of his paintings. For all Sickert’s Francophilia there are almost none of his works in France so Bemberg’s pictures offer a rare chance for French visitors to see his work on home soil. The collector’s greatest love, however, was for Bonnard and he amassed 31 of his works, the greatest number outside the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée Bonnard in Le Cannet, north of Cannes. Together, in a long room by themselves, they show the range of both his career and subject matter – landscapes and marine pictures, cafe scenes and still lifes, interiors and a woman washing – from the 1890s through to the 1940s.

A gallery full of Bonnards in the Hôtel d’Assézat. Photo: Mathieu Rabeau; © RMN-Grand Palais (Fondation Bemberg)

Bemberg said that the favourite among his Bonnards was Red and Yellow Apples (1920), a high-toned still life of fruit on a red gingham tablecloth that is bright and upbeat but perhaps little more than decorative. There are numerous other works in his gathering that show a more interesting side of Bonnard, not least the two self-portraits of 1933 and 1945 that are tonally distant from the airiness and colour of most of his other paintings displayed here.

What is missing among the Bonnards is a painting of his wife, Marthe, in the bath. However this, suggests Debenedetti, is characteristic of Bemberg, who, she says, never collected ‘expected’ works or had a pre-conceived scheme, wanting an obvious Picasso, say, or Matisse or Pissarro. What he looked for in his pictures was an ‘emotional shock’. So, among the numerous familiar names there are a large number that seem unrepresentative of the individual artist and are perhaps all the more interesting for that.

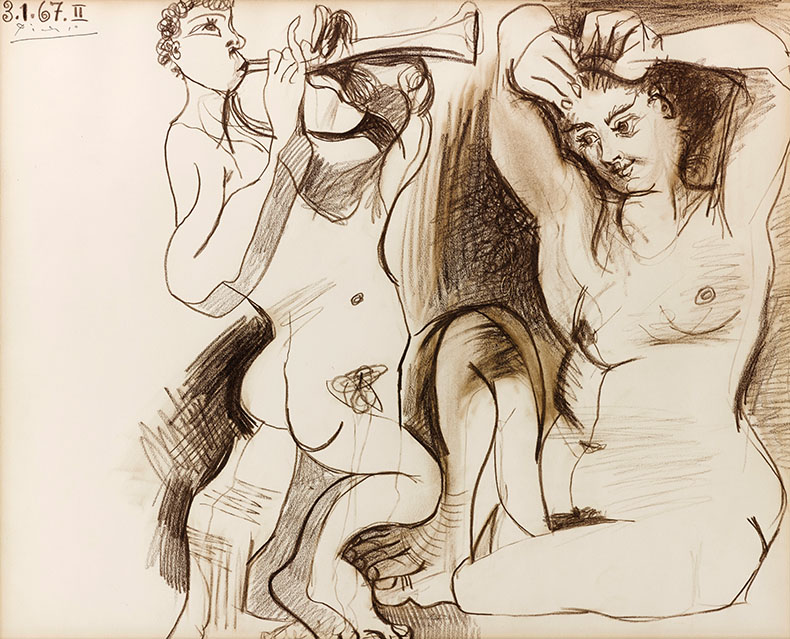

The trait can be spotted throughout the rooms. There is, for example, a Belliniesque Madonna and Child by Vittore Carpaccio (c. 1485–90) rather than a young-man-in-striped-hose Venetian scene; the Schiele in the collection is not a drawing or watercolour of a semi-clothed attenuated figure but a rapid oil sketch of a garden pavilion and flowers; Bemberg’s example of Georges Braque is neither a cubist work nor a dove but a sunny Fauvist view from a balcony; his pair of Matisses, meanwhile, are restrained, low-toned port views that offer little hint of the colour-saturation to come. Bemberg himself described this quirk: ‘I like the Picassos that one likes when one doesn’t like Picasso.’

The Couple (1967), Pablo Picasso. Fondation Bemberg Toulouse. Photo: Mathieu Rabeau; © RMN-Grand Palais (Fondation Bemberg)

This same interest in the margins means that there is also relatively little religion on show (Bemberg was, says Debenedetti, a ‘humanist’) and, with the glaring exception of a frankly explicit, sheet-tousled brothel scene by Toulouse-Lautrec (Maison de la rue des Moulins, Rolande, 1894), little overt sensuality either. There are some nudes, however, not least among the bronzes by Aristide Maillol and Roger de la Fresnaye and also the greatest of Bemberg’s sculptures, Mars, made by Giambologna in the 1580s. The V&A has a later version, not quite as fine, so Debenedetti can maintain an emotional link to her previous employer.

For her, one of the other attractions of the Fondation Bemberg is that the collection is evolving. It is a private museum, albeit hosted by the city of Toulouse, but with its own trust to fund acquisitions. When buying new works the aim is to ‘mimic’ what Bemberg himself might have done, says Debenedetti – no straightforward task – rather than fill obvious chronological gaps. Among recently acquired pieces are a pair of female figures holding baskets of fruit painted by Nicolas Tournier, the accomplished Caravaggist painter who died in Toulouse in around 1639; Francisco de Zurbarán’s painting of a rarely depicted scene in which the young Christ pricks his finger on a crown of thorns (c. 1645–50); and a spectacular terracotta tondo by the Genoese sculptor Angelo De’ Rossi, The Adoration of the Shepherds (1711), made as a reception piece on his election to the Accademia di San Luca in Rome.

In 1995, at the inauguration of the Fondation, Bemberg delivered a short speech which concluded with his wish that, ‘Now that my pictures are with you, I hope – if you feel like it – that you will invite me from time to time to return to see them in Toulouse. That will give me pleasure.’ The reticence and modesty were, by all accounts, typical of the man – there is a story that he would sometimes return to the Fondation to look at the art incognito. If his character remains somewhat elusive, however, his collection now offers something distinctly and rewardingly tangible.

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.