‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Explore now.

Each week we bring you four of the most interesting objects from the world’s museums, galleries and art institutions, hand-picked to mark significant moments in the calendar.

In the hands of Egon Schiele, who was born 135 years ago this week, the human body was an expression of raw emotional truth. With their sickly pallor and fierce red accents, his angular, contorted figures – often based on his own body – broke radically from academic traditions to express the psychological tumult beneath the surface. At times recalling the twisted crucifixions of Matthias Grünewald and paintings by Goya, whose subjects often seem tortured both mentally and physically, Schiele’s work anticipated that of contemporary figurative painters whose stock in trade is bodily distortion. These artists have understood that the human form, when liberated from anatomical correctness, can communicate inner states of being.

The expressive body in art reveals many things we typically conceal. By deliberately distorting proportions, fracturing limbs or saturating flesh with unnatural colour, artists are able to trigger visceral responses in viewers; this is demonstrated not only by Schiele’s brittle self-portraiture but also by Francis Bacon’s howling popes or Jenny Saville’s monumental nudes. This week we examine four works in which the human form itself lays bare psychological states both recognisable and highly personal.

Dancer Looking at the Sole of her Right Foot (c. 1919–20), Edgar Degas. The Courtauld, London. Photo: © The Courtauld

Dancer Looking at the Sole of her Right Foot (c. 1919–20), Edgar Degas

The Courtauld, London

Edgar Degas’s interest in the human body is obvious in his pastel sketches and paintings of ballet dancers rehearsing in Paris. Troupes of bodies hold challenging poses, caught in mid-motion; an individual is picked out in the middle of a stage or rehearsal room. Yet these works are often as much about the surface of the tutus and the light in the room as they are a mapping of the human body. It was in his bronzes that Degas really got to grips with physical effort and strain. In this sculpture a dancer looks at the sole of her foot in a pose that Degas’s model would have had to hold for hours at a time. The surface of the bronze is worked to summon the texture of flesh and make apparent the effort in capturing a momentary pose. Click here to find out more on Bloomberg Connects.

Lyricist (1911), Egon Schiele. Leopold Museum, Vienna

Lyricist (1911), Egon Schiele

Leopold Museum, Vienna

Schiele portrays himself in an anatomically impossible manner – back twisted, head sharply angled, limbs contorted. His pallid flesh contrasts with his bright red genitalia and his navel, which has been deliberately misplaced to create an intriguing visual tension. The painting, which conveys a sense of rawness through urgent brushstrokes with no under-drawing, literally squares up to viewers on an even-sided canvas. Created in a period of febrile artistic evolution for Schiele, this self-portrait as ‘lyricist’ suggests that his body itself is an instrument, each physical distortion sounding a very particular note. Click here to find out more.

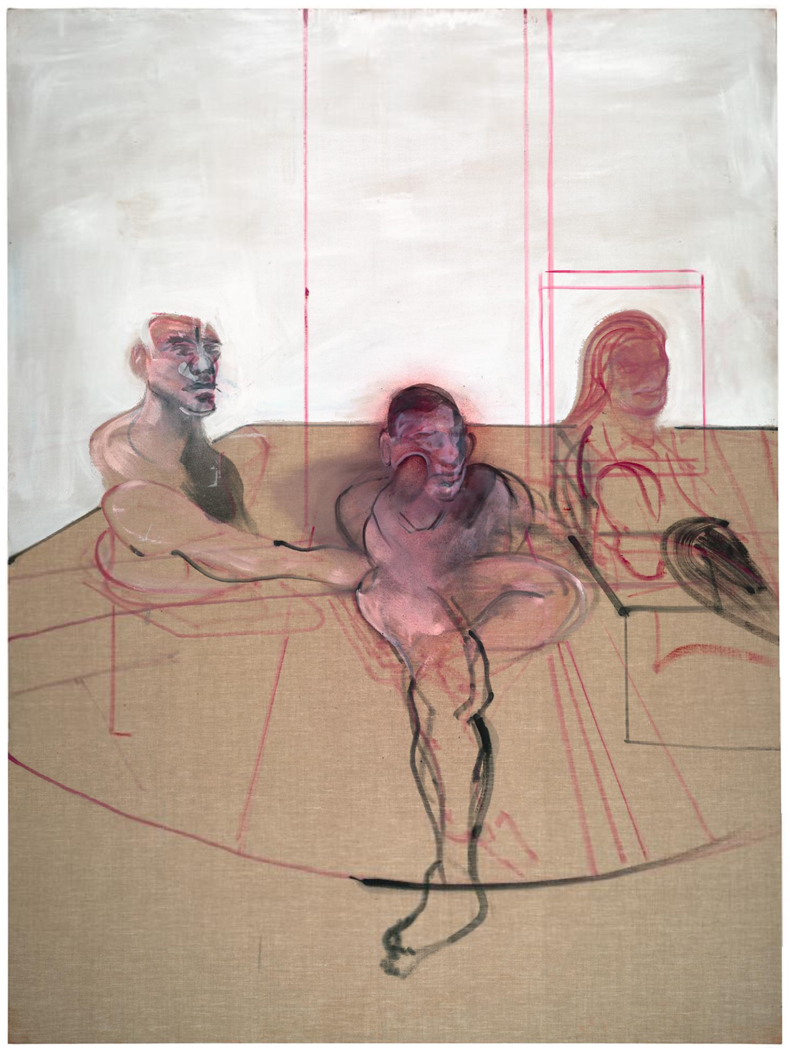

Three Figures (c. 1982), Francis Bacon. Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin. Photo: © Hugh Lane Gallery; © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved/DACS

Three Figures (c. 1982), Francis Bacon

Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin

Unfinished yet powerfully evocative, this late-career work demonstrates Bacon’s facility for transforming the human form into meat-like abstractions. Distinctive smears and twists of paint construct bodies that seem simultaneously to come together and disintegrate. Its incomplete status allows us to see the painter’s technique – how his initial exploratory outlines evolve into areas of concentrated colour that suggest both physical presence and psychological disintegration. Bacon’s figures exist in a state of perpetual becoming and unbecoming. Click here to read more.

Service de Luxe (1999), Cecily Brown. Rubell Museum, Miami

Service de Luxe (1999), Cecily Brown

Rubell Museum, Miami

A female figure dissolves into fleshy brushstrokes, her reclining form barely distinguishable from the lurid environment that threatens to consume her. Brown’s sensuous application of paint mirrors the carnal subject matter, blurring boundaries between body and background. Through deliberate imprecision, Brown creates a tension between figuration and abstraction, offering glimpses of corporeal reality that remain tantalisingly out of reach. Click here to discover more.

![]() ‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Explore now.

‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Explore now.