‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the Bloomberg Connects app here to access hundreds of digital guides and explore compelling audio and behind-the-scenes perspectives.

Each week we bring you four of the most interesting objects from the world’s museums, galleries and art institutions, hand-picked to mark significant moments in the calendar.

Charles I, who ascended the English throne 400 years ago this week, on 27 March 1625, was a passionate collector and patron. He is renowned for his commissions from artists such as Van Dyck, Rubens and Bernini, as well as for collecting the Old Masters that would later form the core of the Royal Collection.

Royal patronage has long served as an expression of power and a tool of cultural diplomacy. Through their support of artists, rulers could shape their public image, demonstrate their sophistication and create lasting monuments to their reign. From the Medici in Florence to the Mughal emperors, royal patrons have played a crucial role in art history, enabling artists to create works of unprecedented ambition and scale. This week we examine four works that illuminate different aspects of royal patronage.

Diane de Poitiers, Madame de Valentinois (after 1547), school of François Clouet. Graves Gallery, Sheffield. Courtesy Sheffield Museums

Diane de Poitiers, Madame de Valentinois (after 1547), school of François Clouet

Graves Gallery, Sheffield

This austere yet elegant portrait depicts Henri II of France’s mistress, who wielded significant power at court and became one of Henry’s most trusted advisors, sparking tensions between her and the king’s wife, Catherine de’ Medici. Throughout her time in court, Mme de Valentinois patronised many artists, architects and writers, including Jean Goujon, Philibert Delorme and Pierre de Ronsard. Here, dressed in the widow’s colours of black and white, the subject’s pearl necklaces and rings indicate her high status. Click here to find out more on Bloomberg Connects.

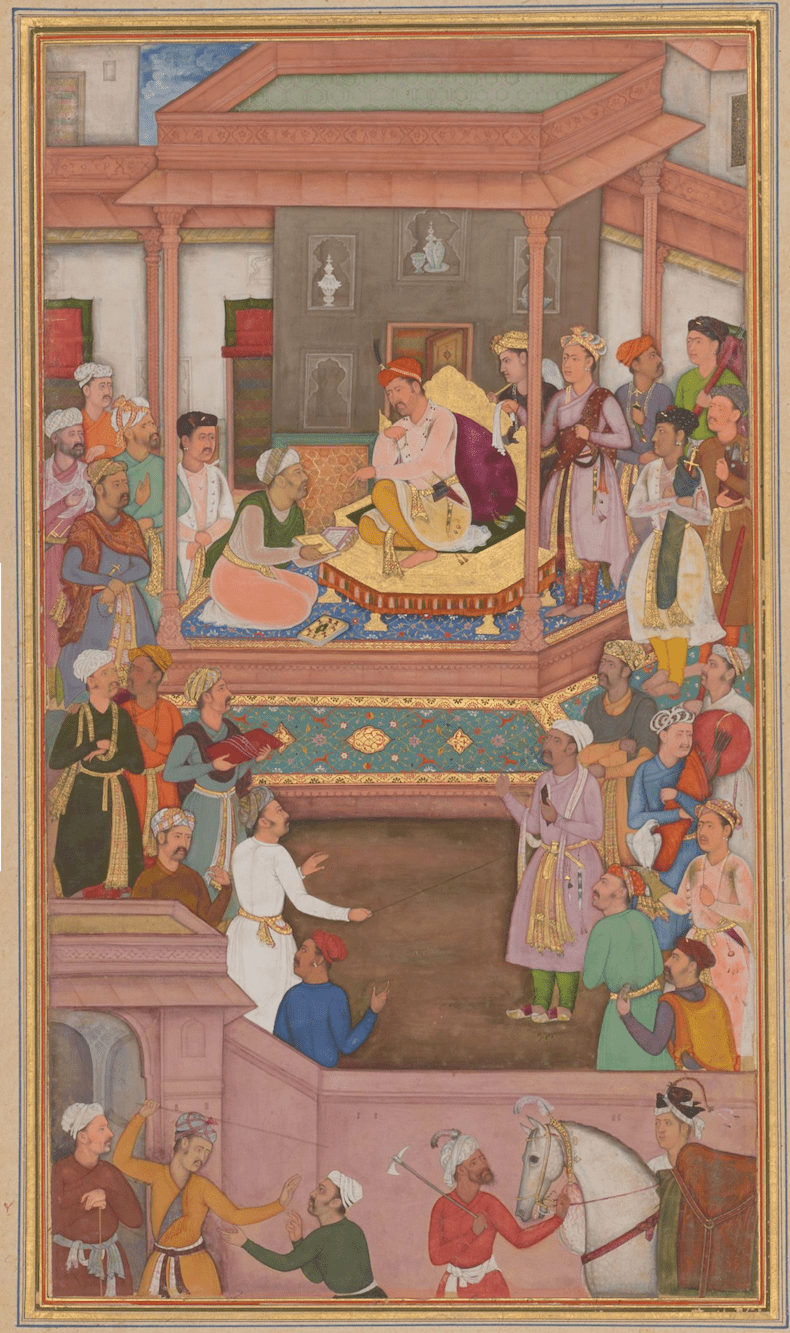

Illustration from the History of Akbar (1603–05) by Abu’l-Fazl, showing Abu’l-Fazl presenting Akbar with the second volume of the Emperor’s biography. Chester Beatty Library, Dublin

Abu’l-Fazl Presents Akbar with the Second Volume of the Emperor’s Biography, from the History of Akbar (1603–5), Abu’l-Fazl

Chester Beatty Library, Dublin

This richly detailed manuscript illustration captures a moment of ceremonial presentation at the Mughal court. The scene shows Abu’l-Fazl, court historian and grand vizier of the Mughal empire, offering Emperor Akbar a volume of his biography, which Akbar had commissioned. The manuscript in which this miniature is found was written and compiled by Abu’l-Fazl himself; it is a chronicle of the Mughal empire under Akbar’s rule, and was intended in part to secure the emperor’s legacy. Click here to learn more.

Charles I (1635–before June 1636), Anthony van Dyck. Royal Collection Trust. Photo: © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Charles I (1635–before June 1636), Anthony van Dyck

Royal Collection, London

This innovative portrait, showing Charles from three different angles, was created not as a standalone work but as a study from which Van Dyck’s contemporary Bernini could create a marble bust of the king. (Bernini did produce a bust, but it was destroyed by a fire in Whitehall Palace in 1698.) The work was painted at the height of Charles I’s artistic patronage, before the beginning of the civil war that would eventually lead to his downfall and execution. Click here to find out more.

Portrait of Agustín de Iturbide, Emperor of Mexico (1822), Josephus Arias Huarte. Philadelphia Museum of Art

Portrait of Agustín de Iturbide, Emperor of Mexico (1822), Josephus Arias Huarte

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Commissioned during Iturbide’s brief reign as Emperor of Mexico, this portrait reveals how rulers have tried to use art to establish legitimacy. In this case, however, that attempt was unsuccessful: Iturbide was deposed and then executed by firing squad just two years after this portrait was painted. What’s more, X-ray analysis has found that this work and its companion painting of Empress Ana María were painted over earlier portraits of King Charles IV of Spain and his wife, Queen Maria Luisa of Parma, making this attempt at imperial image-making seem even more hubristic. Click here to read more.

![]() ‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here or scan the QR code to access hundreds of digital guides, anytime, anywhere.

‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here or scan the QR code to access hundreds of digital guides, anytime, anywhere.