‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app. Bloomberg Connects lets you access museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here to access digital guides and explore a variety of content.

‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app. Bloomberg Connects lets you access museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here to access digital guides and explore a variety of content.

Each week we bring you four of the most interesting objects from the world’s museums, galleries and art institutions, hand-picked to mark significant moments in the calendar.

Throughout history, women have made profound contributions to medical knowledge and healthcare practices. Peseshet, who is often cited as the first known female doctor, was working in Egypt as long ago as 2500 BC. Cleopatra the Physician, who lived in Greece toward the end of the 1st century AD, wrote two texts on gynaecology that went on to be translated into Latin. Some of her work went on to be quoted by the renowned ancient physician Galen. More recently, Bristol-born doctor Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910) was the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States; her achievement was commemorated on a US postage stamp in 1974.

160 years ago today, Rebecca Lee Crumpler graduated from the New England Female Medical College, making her the first Black woman to become a doctor of medicine in the United States. To honour this achievement, we look at four works that celebrate women who have shaped or symbolised healthcare.

Portret van Hildegaard (1701), Romeyn de Hooghe. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Portret van Hildegard (1701), Romeyn de Hooghe

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Published in the 1701 edition of Gottfried Arnold’s Impartial History of the Church and Heretics (1699–1700), this portrait by renowned engraver and caricaturist Romeyn de Hooghe shows Hildegard of Bingen: saint, polymath and visionary. Around 1151, Hildegard started work on a guide to pathology, natural science and medicine that resulted in two extraordinary texts: Causae et Curae and Physica, seemingly the first of their kind. Click here to find out more.

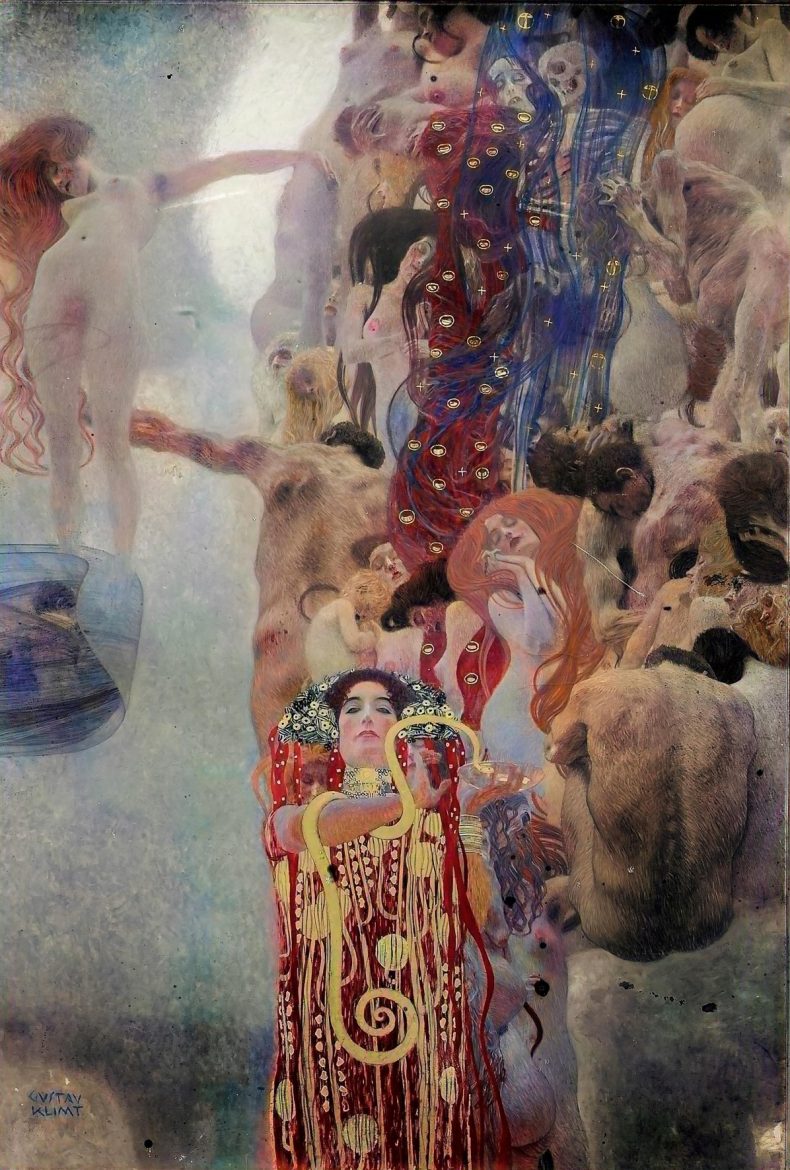

Medicine (1900–07; reconstructed 2021), Gustav Klimt. Belvedere, Vienna

Medicine (1900–07, reconstructed 2021), Gustav Klimt

Belvedere, Vienna

Hygieia, Greek goddess of medicine and cleanliness, appears majestic in red and gold towards the bottom of Klimt’s Medicine, recently reconstructed with the help of AI after it was burned in the last days of the Second World War. Draped over her arm is a golden snake, recalling the snake curled around the Rod of Asclepius, the ancient Greek god of medicine. Click here to read more.

Trotula place setting from The Dinner Party (1979), Judy Chicago. Brooklyn Museum, New York. Photo: © Donald Woodman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; © Judy Chicago/ARS, New York

Trotula place setting from The Dinner Party (1979), Judy Chicago

Brooklyn Museum, New York

Trota of Salerno was an 11th- or 12th-century medical practitioner and influential writer, often considered the world’s first gynaecologist. An anthology text that compiled some of her therapies along with those of other physicians became known as Trotula, which in Chicago’s time was still understood to be the name of the figure as well as of the text. Here, Trota is honoured with a place setting at Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, with a motif commemorating her contribution to women’s healthcare. The quilting of the tree-of-life table runner evokes baby blankets – a tribute to Trota’s specialism. Click here to learn more.

The Spirit of Sea View (2020; detail), Yana Dimitrova. Mural at Sea View Hospital, Staten Island; courtesy NYC Health + Hospitals

The Spirit of Sea View (2020), Yana Dimitrova

Mural at Sea View Hospital, Staten Island, NYC Health + Hospitals

This mural at Sea View Hospital in Staten Island depicts the hospital’s long history of serving the most vulnerable populations of New York. The work gives particular prominence to the ‘Black Angels’, a term that refers to the approximately 300 African American nurses from all over the country who provided critical care to patients at Sea View during the tuberculosis pandemic between 1928 and 1960. Click here to find out more on the Bloomberg Connects app.

![]() ‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app. Bloomberg Connects lets you access museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here to access digital guides and explore a variety of content or scan the QR code.

‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app. Bloomberg Connects lets you access museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here to access digital guides and explore a variety of content or scan the QR code.