‘Four things to see this week’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app. Bloomberg Connects lets you access museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here to access digital guides and explore a variety of content.

‘Four things to see this week’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app. Bloomberg Connects lets you access museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here to access digital guides and explore a variety of content.

Each week we bring you four of the most interesting objects from the world’s museums, galleries and art institutions, hand-picked to mark significant moments in the calendar.

This week, more than a billion people are ushering in a new year with holidays and celebrations to mark the first new moon of the lunar calendar. For many East Asian communities, each year is associated with one of 12 animals from the Chinese zodiac; now, the year of the dragon is nigh – and as the dragon is the zodiac’s only mythical creature, it’s considered an especially auspicious year.

Across the world, dragons symbolise power, protection, luck and both the destructive and creative forces of nature. In Chinese culture the dragon has historically been associated with water – revered for its importance to life itself – and imperial strength; in more recent years it has come to connote prosperity, harmony and good fortune. In the West, including in Norse folklore, they are more commonly fearsome, fire-breathing monsters and sometimes guardians of treasure. Nagas, serpent-like creatures akin to dragons, play a significant role in Hindu mythology, often associated with water and fertility. Here we explore four depictions of dragons from very different cultural contexts.

Saint George and the Dragon (c. 1470), Paolo Uccello. National Gallery, London

1. Saint George and the Dragon (c. 1470), Paolo Uccello

National Gallery, London

In this imagining of Saint George’s triumph over the dragon, Uccello shows the saint plunging a spear into the creature’s head while the princess, presumably just rescued from her role as human tribute, holds the blood-drooling dragon by a leash in a surprisingly relaxed fashion. The man-eating, cave-dwelling beast presented here is mostly typical of dragons in Western culture, though the oddly pitiable expression on the dragon’s face is unusual. Click here to find out more.

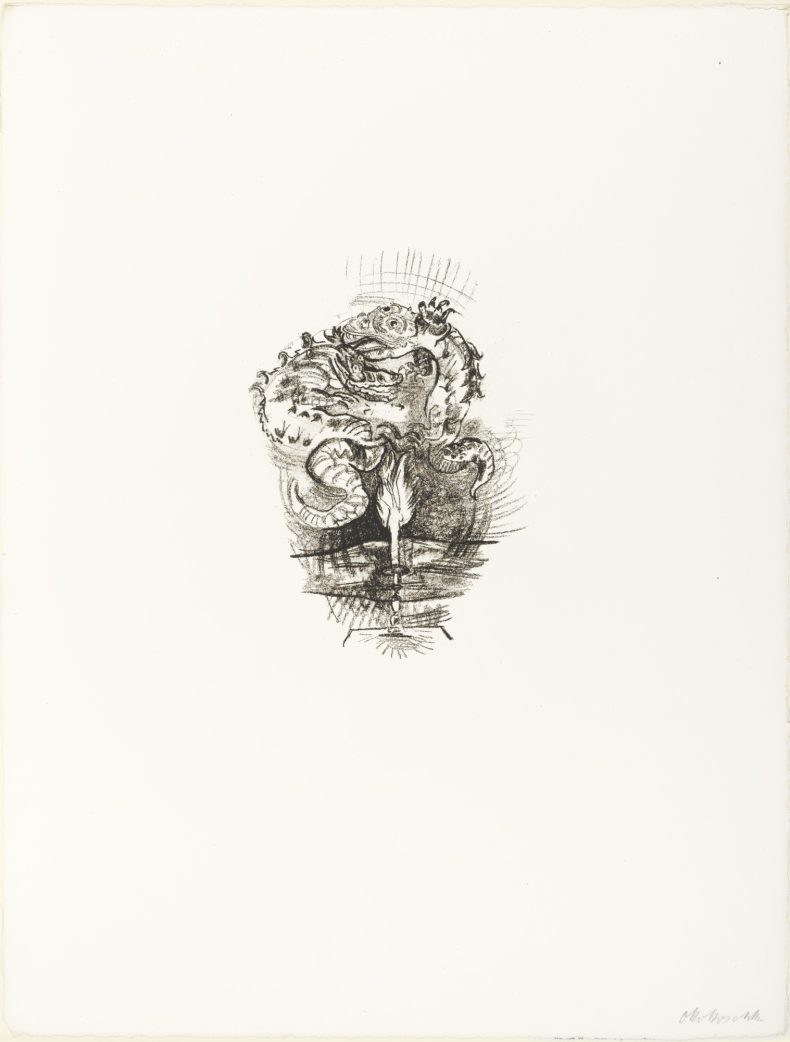

Dragons over a Flame (1914), Oskar Kokoschka. Museum of Modern Art, New York; © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ProLitteris, Zurich

2. Dragons over a Flame (1914, published 1916), Oskar Kokoschka

Museum of Modern Art, New York

In Dragons over a Flame, part of a series of 11 lithographs, Kokoschka confronts the heartbreak that ensued from his turbulent romance with Alma Mahler, her abortion and her rejection of his marriage proposal. The entwined dragons vividly depict his desperate efforts to shield Mahler from nightmarish reptilian visions during her pregnancy. Click here to learn more.

Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate, Vorderasiatisches Museum. Photo: Olaf M. Teßmer; © Pergamon Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

3. Dragon, Ishtar Gate reconstruction

Pergamon Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

This is one of a number of Babylonian dragons, or mushussu, who guard the Ishtar Gate, built under King Nebuchadnezzar II (604–562 BCE) for the goddess Ishtar, and restored and reconstructed in Berlin around a century ago. Combining features from an array of animals, including feline forelegs, a scaly serpentine body and a snake-like tongue, these mythological hybrids were sacred servants. Click here to find out more.

The Captives (c. 1915), Evelyn de Morgan. De Morgan Museum, Barnsley; © Trustees of the De Morgan Foundation

4. The Captives, c. 1915, Evelyn de Morgan

Draped in jewel-toned classical robes, five women are tormented by green dragons, one fork-tongued and one breathing fire. The stalactites and stalagmites of the surrounding cave appear almost fleshy or fang-like, as though the women are already held within the mouth or belly of a beast. The Captives was painted during the First World War, when De Morgan often used her symbolist approach to represent the evils and dangers of war through dragons and vicious beasts. Click here to find out more on the Bloomberg Connects app.

![]() ‘Four things to see this week’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app. Bloomberg Connects lets you access museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here to access digital guides and explore a variety of content or scan the QR code.

‘Four things to see this week’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app. Bloomberg Connects lets you access museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Download the app here to access digital guides and explore a variety of content or scan the QR code.