On 24 November 2020, France’s National Assembly voted to pass a ‘global security’ bill. If adopted by the Senate this month, the law will give expanded powers to municipal police and security contractors and allow the police to carry out surveillance through security cameras and drones. The most criticised section of the proposed bill, article 24, will punish with a fine of 45,000 euros and a one-year prison sentence any person broadcasting images identifying police officers ‘with the intention of damaging their physical or psychological integrity’.

There has been strong opposition to the bill, led by journalists’ unions and by the Ligue des droits de l’homme. On 28 November, the biggest of a series of protests against the bill took place in in several French cities (500,000 took part according to the organisers; 133,000 according to the interior ministry). Societies of journalists representing media outlets across the political spectrum (from L’Humanité to Le Figaro), photographers and film-makers including Raymond Depardon, Jacques Audiard, David Dufresne and Alice Diop signed a petition opposing the law.

Law professor Karine Parrot is the co-director of a film about the proposed bill, which is titled Sécurité globale, de quel droit? (‘Global security, by which right?’). ‘It strikes me as unbelievable that we adopt laws the effects of which will be so far-reaching while we are in a public health state of emergency, with restricted freedom to protest,’ she says, referring to a recently voted bill setting the budget for academic research and to the security bill. ‘They were silly to call [the bill] “global security”, as it’s a frightening name. You’ll notice that it’s article 24, the only section that is written in understandable French, with a subject, a verb and a complement, that sparked things off,’ she adds. Despite its syntactical coherence, Parrot believes article 24 might be discarded by senators for being too vague. She thinks it’s not even the most dangerous section of the proposed bill.

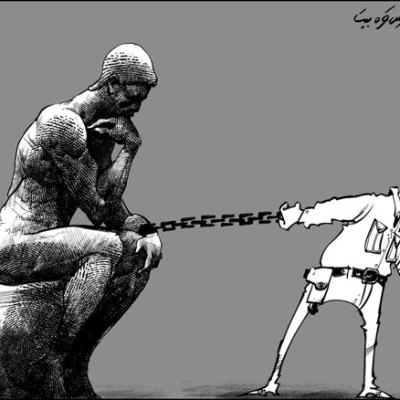

In recent years there has been a rising awareness of police brutality in France. This was prompted in part by the campaign surrounding the death of a young Black man called Adama Traoré after a police intervention in 2016, which was reignited by the Black Lives Matter movement. A video was the starting point of the Benalla scandal (Alexandre Benalla, a security adviser of Emmanuel Macron, beat up a protester during a May Day protest in 2016 while impersonating a police officer). In January 2020, videos shot by passers-by showed that delivery driver Cédric Chouviat had died after being held in a choke-hold by police officers, contradicting the first statement issued by the Paris Police Prefecture.

During the Gilets Jaunes protests, journalist David Dufresne documented police brutality against protesters and journalists in a series of tweets that would always start by: ‘Allo, place Beauvau, c’est pour un signalement’ (‘Allo, place Beauvau [shorthand for France’s interior ministry], I wish to report the following’). In September 2020 he released a documentary called The Monopoly of Violence (French title: Un pays qui se tient sage), which relies heavily on videos showing police brutality during the Gilets Jaunes protests. The film was recently nominated for a César award for best documentary. Critics of the proposed bill claim such a film couldn’t even exist if it becomes more difficult to film the police.

In October, artist Paolo Cirio was set to show a large installation as part of a group exhibition in art school Le Fresnoy, in Tourcoing. Titled Capture, his project features the faces of 4,000 French police officers processed by a facial recognition software. On Twitter, interior minister Gérald Darmanin, who was mayor of Tourcoing from 2014 to 2017, accused Cirio of putting in danger ‘men and women who put their lives at risk to protect us’ and demanded the installation be taken down. The work was boarded up and Cirio shut down the accompanying website.

Supporters of the bill among politicians from Macron’s party, La République En Marche, claim it won’t affect freedom to inform and freedom of expression. Former interior minister Christophe Castaner wrote in Le Journal de Dimanche that with the latest version of article 24: ‘Freedom of the press is fully protected, the right to inform acknowledged.’

Raphaël Kempf, a criminal defence attorney, says, ‘These [politicians] have a conception of the law that is completely disconnected from the way it’s used by the police. There’s a hypocrisy in their argument. Laws are not only implemented in courts. This law would give arbitrary powers to the police. When someone appears in court for having photographed or filmed the police it’s already too late. They will already have been detained.’

People holds placard depicting an eye as they gather in Paris on 28 November to protest against the expansion of surveillance proposed by the new French security law. Photo: Thomas Coex/AFP via Getty Images

The security bill was adopted at the National Assembly with an amendment suggested by the government that states article 24 is not to infringe on the right to inform. This is far from the ‘comprehensive rewrite’ the government promised in December. In the same week as the vote, two incidents served as reminders that videos play a key role in shedding light on police violence. On the evening of 23 November, migrants who had been expelled from a camp in Saint-Denis without being re-housed set up their tents on Place de la République, in the centre of Paris, with the help of Utopia 56, an organisation supporting migrants. Videos of the police operation showed officers seizing tents, using tear gas, dispersal grenades and batons. A photographer was hit on the head by a police baton and had to stop reporting. Darmanin, who is seen as the main defender of the proposed bill and of article 24 in particular, took to Twitter to say some of the images were shocking. He later announced the case had been referred to France’s police watchdog.

On 26 November, media outlet Loopsider published CCTV images showing police officers beating a Black music producer named Michel Zecler in his recording studio on 21 November. Zecler was initially detained, after officers accused him of assault and resisting arrest. It was only when the authorities saw the CCTV recording of the incident that he was cleared and released. Darmanin announced the officers had been suspended. ‘The images that we have all seen of Michel Zecler’s assault are unacceptable. They shame us,’ Macron wrote on Twitter.

‘All politicians said these images were shocking,’ Dominique Pradalié, the general secretary of France’s union of journalists, tells me. ‘None of them said the actions themselves were shocking. This made me really sad. They are in complete denial, either because they are in their bubble, or because they feel they need authoritarian policies to remain in power. We reported 200 cases of police brutality against journalists during the Gilets Jaunes protests. Two hundred means this is systemic, and the result of a political choice.’

Photographer Sadak Souici explains that working conditions for photojournalists active in France have deteriorated, that the protective gear they use to be able to work (gas masks and helmets) is often seized by the police and that they are targeted while being clearly identified as press. Emmanuel Macron’s trips are now ‘pooled’, he says, which means only approved journalists and photographers are allowed to cover them.

In September 2020, a new document organising law enforcement emanating from the Interior Ministry (SNMO) stipulated that journalists have to disperse when the order to do so is given during a protest. At the end of 2020, a journalist and a photojournalist filed a complaint to Lille’s administrative court, claiming the police had repeatedly prevented them from covering the eviction of migrants’ camps in Grande-Synthe, in Northern France. On 3 February 2021, in a shock ruling, the Conseil d’État ruled the fact that the journalists had been kept outside of a ‘security perimeter’ had ‘not constituted a serious and manifestly illegal infringement of the journalist’s ability to do their work.’

‘Police officers see that we are taking a professional image which will be clear and in focus, and might incriminate them,’ Souici says, ‘but we need images just as much as we need words to explain what is going on in France. Article 24 would prevent us from taking pictures of what is happening. We would be blind. What happens when there’s no images? We’d head towards nothingness.’