From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Last October, in the days after the heist at the Louvre, I couldn’t help wishing that the film-maker Frederick Wiseman had made a documentary about the world’s most visited museum. As its president, Laurence des Cars, defended the security system – while admitting the museum had failed in its responsibilities to protect its collection – one did wonder what on earth went on behind closed doors.

From his first film, Titicut Follies (1967), about an insane asylum in Massachusetts, to his 43rd, Menus-Plaisirs – Les Troisgros (2023), about a three-star Michelin restaurant in France, Wiseman has examined an incredible range of institutions. He has made films about hospitals, high schools, modelling agencies, law courts, abattoirs, sardine factories, boxing gyms and zoos, to name just a few. Most of these documentaries are set in North America but a handful are set in Europe, mostly France, where he enjoys the widest recognition and distribution.

Some of Wiseman’s films are about arts institutions: Ballet (1995), about American Ballet Theatre in New York; La Comédie-Française ou l’amour joué (1996); La Danse (2009), about the Paris Opera Ballet; National Gallery (2014) and Ex Libris: The New York Public Library (2017). Though perhaps my hope for a film about the Louvre is misplaced, since these films don’t exactly tell us much about how the institutions are run.

In each of the above, Wiseman spends around three hours first showing us the institutions as physical buildings, in their London, Paris and New York settings, then entering the departments and rooms where staff work and students train. He also includes extensive footage of what these institutions produce: ballets, plays, talks by authors, exhibitions. But he has little interest in exploring the intricacies of bureaucracies and power structures.

None of Wiseman’s films are conventional documentaries that methodically go through how a place works, via explanatory scenes and interviews with staff who speak to camera, their names and titles clearly indicated. We are left to work things out. We make our own mental sketch of the key players and connect the dots as to how things might function. We are, in other words, active spectators, gleaning what we can and filling in the rest.

The arts documentaries are better approached as timepieces. They offer us a window on to one year in one location (but sometimes more than one building). We learn how people looked, dressed, spoke and interacted. We can also get a taste of some social and political concerns that existed, from staff conversations held around tables in various offices. For example, departmental meetings in National Gallery cover issues including whether the gallery should capitalise on potential free publicity from an upcoming charity race that will end at its entrance, or whether to do so is watering down the museum’s purpose. Another conversation concentrates on the proposed budget for the following year. A woman we presume is the finance director has been cautious doing her sums because of staff payouts and a blockbuster exhibition that will not be repeated in the year ahead.

In Ex Libris the discussions range from the difficulty of catering to both popular and scholarly demands for books, to ways of attracting private investment and how to manage homeless patrons. Should the library ban those who do not read a single book but come in to sleep, or does the institution have a social role to play in New York? While all documentaries present time-specific facts to some extent, in the absence of any broader context discussions like these feel particularly frozen in their year of shooting.

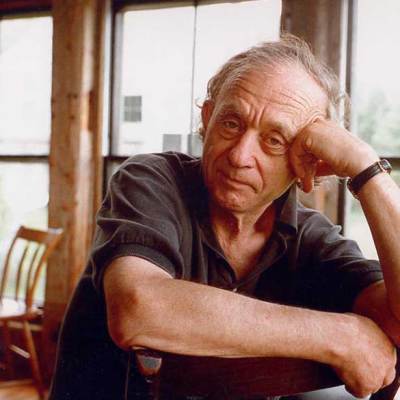

Having met and interviewed Wiseman several times – he is small and wiry, with a mess of curly hair and pixie-like ears – I was struck by how unassuming he is. His films have the same quality, both in tone and method. Wiseman shoots with a team of two or three at most – one person on camera and with him on sound – to avoid creating disturbance. His visual style and montage are unflashy. There is a simple and repetitive quality to them. Establishing shots cut quickly together show locations, starting with the city, then streets, buildings, entrance doors and into the interior hallways and corridors, followed by the rooms where the action occurs. There are several shots locating the National Gallery on Trafalgar Square from various angles, but Wiseman prefers looking down Whitehall to Big Ben. It is a view familiar to tourists, just as we get plenty in Ballet showing the New York skyline. When American Ballet Theatre goes to Athens for a series of outdoor performances, we repeatedly see the Acropolis while the moon in the night sky punctuates the scenes, telling us that time is passing.

These short scenes that introduce the longer ones are reassuring, like the arrow on a map that says, ‘You are here.’ They can also seem a little pedestrian; this is the same visual grammar used in short videos by news agencies. But in Wiseman’s films they are efficient ways of delivering basic information, leaving us free to focus on what then goes on in the long scenes. We are not, as is often the case in documentaries, pummelled with information that takes our attention away from what is happening in the images, nor is there the trace – in noticeable camera movements or aesthetically striking images – of a director reminding us he is there. Indeed, on that note Wiseman is generally suspicious of pictures that look too pretty. One reason he has made two films about high schools – the first in 1968, the second in 1994 – was his embarrassment about what he deemed the excessive stylisation of the first.

Halfway through Ex Libris, Patti Smith is on stage talking about her general lack of interest in working on books with a clear chronology tethered to facts. Writing her memoirs, the word more appropriate to describe her process is ‘braiding’, she says. The same word comes close to describing Wiseman’s own way of working. Broadly speaking, we get a series of long scenes in which issues and people connected to the institution appear and sometimes reappear. Wiseman preserves the complexity, yet allows us to better understand his subject, through vivid strands that become evident over the course of watching.

Watching not one but two films about ballet familiarises us with the daily routines of rehearsals mixed with long pauses of stretching and downtime. However, it is also striking to see how no two institutions are the same – the attitudes and atmospheres at the schools in New York and Paris are distinctively their own. The teachers we meet are as mesmerising to watch as the dancers. All are current or former performers themselves and there is an added fascination to seeing someone be so effortlessly graceful. One can see their bodies shaped by years of practice. In Ballet, there is an extraordinary appearance by the choreographer Agnes de Mille, who is well into her eighties and in a wheelchair. Nevertheless she is in the studio in her starched white blouse and silk pussy bow and, from a few flutters of her hand, you see the dancer still in her. ‘You must look like something that’s absolutely broken, and stuck up in the wind,’ she tells the ballerina she is directing.

One of the most striking features of the arts documentaries is the sheer length of time Wiseman spends showing us the output of thse institutions. His interest in this is not limited to arts organisations: for example, in City Hall (2020) we see plenty of the front-facing activities of the Boston mayor’s office. Zoo (1993) meanwhile spends a lot of time observing the animals as they are viewed by visitors. But the equal balance of day-to-day and end performance is particularly striking in the arts films. Other directors tend to take no more than a cursory glance at the result, since this is generally treated as the part viewers already ‘know’. In Wiseman’s films, it is interspersed with everyday activities, giving them a distinctive tempo – like a piece of music moving between intense sequences and calmer periods.

In the performance scenes, we see what is more familiar. Indeed, being catapulted into the spectacle after watching rehearsals or detailed discussions about, say, a dancer’s schedule, their future with the company or what exactly their left foot should be doing on that musical note is surprising, frustrating even. There is novelty and a sense of discovery in the behind-the-scenes footage, but less so in seeing what we could in theory buy tickets for ourselves. But this disappointment quickly gives way to a feeling unique to Wiseman’s films. By showing us both the daily toil and the end result he is encouraging us to not make the distinction between the two at all.

We watch the performances with the trace of the rehearsal still imprinted on our visual memory; we are seeing the same movements and scenes, but in their most refined form. For example, in Ballet we spend a lot of time time watching the rehearsals of what will eventually close the film, a performance of Romeo and Juliet in Athens. Seeing the final performance, with all the dancers in heavy make-up and costumes, their every effort going into perfecting each move, we watch with the still-vivid memory of baggy pants and leggings, old leotards and bins in the corner of the room. We appreciate the immensity of the work involved in getting to this point of perfection.

At a masterclass I saw at the Centre Pompidou in 2024, the critic Charlotte Garson suggested to Wiseman that he was just as interested in people performing roles as actors or dancers as he was in everyday life. Wiseman agreed. He was, he said, showing ‘the other side, the relationship between the abstract and the day-to-day’. That may be so, but it is worth dwelling on further as it gets us closer to understanding what draws Wiseman to the subject of institutions in the first place. The subject, it should be said, is one he has always defined loosely. He admitted as much at the Pompidou, chuckling at the fact that he had, after all, made a film about the city of Belfast in Maine – to which we could also add Primate (1974), Central Park (1990)and Aspen (1991), none of which are about institutions in the strict sense of the word.

For me, it is not institutions in themselves that are Wiseman’s true subject. They have acted more as an organising factor allowing him to pursue what seems to me to be his real interest: human behaviour and performance as incarnated in our gestures and movements, through our role-playing and daily activity. What, after all, are we watching people do in his films but move and use their bodies in various ways? Understood this way, Wiseman’s documentaries emerge as an enormous visual encyclopaedia of humans in motion, but rooted in a very specific time and place.

For more information about the films of Frederick Wiseman, go to zipporahfilms.com.

From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.