From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

There was a clear correction in the art market in 2023 – auction sales of Old Masters, Impressionist, modern and contemporary art at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips slumped by an eye-watering 27 per cent, according to the data analysis firm ArtTactic. France was not spared and the second half of last year saw a slowdown among the major players, although some of the smaller houses, such as Bonhams Cornette de St Cyr, Ader, Tajan and Piasa, showed positive results.

France has long been a minnow in the global pool, with about 7 per cent of the world market, putting it in fourth place behind the big fish: the United States, China and the United Kingdom. But the French argue that their lowly placing is partly because sectors in which they are strong are not the big-ticket items – that is, modern, Impressionist and contemporary art.

Among fields where the French are still active collectors are Old Master drawings, design, 18th-century furniture, letters and manuscripts. According to specialists, there are also collectors for decorative arts and furniture from the Haute Époque. Christie’s moved its Old Master drawings, Asian art and design sales to Paris last year. ‘The markets for these sectors are centred in Paris rather than in London now,’ explains Cécile Verdier, president of Christie’s France, ‘and France has a rich seam of experts, restorers and specialist dealers.’

In 2023 Christie’s hit the jackpot with one design piece, François-Xavier Lalanne’s Rhinocrétaire I from 1964. Bought that year by Jeanine de Goldschmidt, partner of the famed art critic Pierre Restany, it had remained in the family ever since. It came to auction in October 2023 with an estimate of €4m–€6m – and made a stunning €18.3m.

Saint Holding a Cross (n.d.), Domenico Beccafumi. Bonhams Cornette de St Cyr, €241,700

While this item had a clear provenance, many pieces do not. Verdier points out that the French system of inheritance under the Code Napoléon, which mandates the division of assets between heirs after a death, means that ‘Each generation has to split up everything, things get dispersed. Some come on the market immediately, others are stuffed in the attics and basements of manors and chateaux, and get forgotten. There is still a reservoir of discoveries to be made.’

Finding such hidden treasures is the forte of the French specialist Eric Turquin, an art historian who works on a commission basis for a number of auctioneers. ‘France has a long tradition of collecting Old Master drawings, and of course has the leading fair in the field, the Salon du Dessin,’ he says, ‘and there is a group of very active collectors here.’

Turquin explains, ‘In the 18th century, the pinnacle of French power and wealth, there were many collectors, of Dutch, French, Italian drawings, and extraordinary collections were built up. But after the French Revolution, everything changed, including taste, and the 19th-century collector preferred the art of the revolution – an art that was virile, violent. Artists such as Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard went completely out of fashion. Provenance and attributions were lost.’

As an illustration, he points to two Fragonards which had initially belonged to the same collector but were separated in the early 20th century and lost their attributions. One, Young Girl in a Hat (1770–75), sold with auctioneers Boisgirard-Antonini for five times its estimate at €3.3m last December. The other, A Philosopher Reading (c. 1768–70), made €7.7m at Enchères Champagne auction house in 2022. Neither vendor was aware that the works had initially come from the same source; Turquin was able to re-establish their provenance and author.

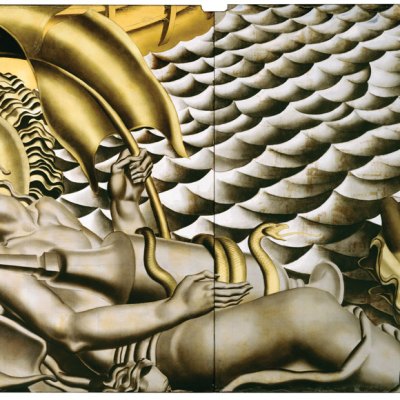

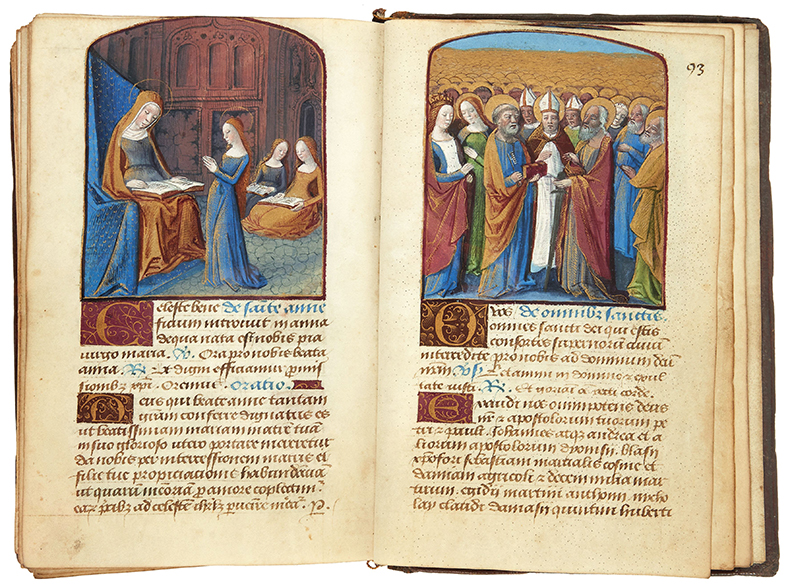

The Hours of Renée de Bourbon-Vendôme (c. 1480–85), attributed to Bourges artists. Artcurial, €121,059

One drawing that did well came from the collection of Alain Delon, sold by what is now Bonhams Cornette de St Cyr, the French auction house acquired by Bonhams in 2022: in June 2023 a drawing of a saint by Domenico Beccafumi (c. 1486–1551) fetched €241,700, well over its estimate of €50,000–€60,000 – the top price of a number of drawings the film star had collected.

Another field that attracts French buyers is books and manuscripts and this despite the massive Aristophil scandal, a scam that ran for decades and bilked thousands of investors out of almost €1bn when they bought shares in massively overvalued documents, including letters, manuscripts and signatures. Nevertheless, there are still many collectors: according to Verdier, 90 per cent of buyers are either French or Francophone.

‘The market is stable, and collectors are continuing to buy, but only for the best quality pieces with interesting provenances,’ says Frédéric Harnisch, director at Artcurial, the largest French auction house after Sotheby’s and Christie’s. He gives as an example the sale of a 15th-century book of hours which made a within-estimate €121,059 in March 2023 – ‘A really fascinating rediscovery’.

Another surprise is the revived market for 18th-century furniture, which has seen an uptick after a long period of decline. Again, this is despite an ongoing scandal in which the Louvre and Versailles turned out to have acquired counterfeits.

Young Girl in a Hat (1770–75), Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Boisgirard-Antonini, €3.3m

Specialists say this renewed interest is directly attributable to the Covid pandemic. ‘As a result of that period of confinement in the city, Parisians started buying historic properties in the countryside. And they are buying classic furniture for them,’ says Alex- andre de La Forest Divonne, auctioneer with Coutau-Bégarie, one of 83 auction houses that operate at the central saleroom Drouot. He says that small pieces, with good provenance and preferably stamped (estampillé), are the most sought after, but cites the sale of a bureau plat from about 1770, ‘in the Grecian style’, which fetched double its estimate at €193,200. Buyers are now very careful about provenance – a photograph of the bureau in situ c. 1910 added to its allure. Filippo Passadore, director of furniture and objets d’art at Artcurial, agrees about the popularity of country houses in the pandemic, and adds: ‘The reopening of the Hôtel de la Marine [the refurbishment was financed by the Qatari Al Thani dynasty and shows part of its collections] allowed people to rediscover classic furniture,’ he says: ‘But they only want very high-quality pieces, signed, with solid provenance.’ He mentions a Louis XVI games table that Artcurial sold in June 2023 for €236,160 – almost five times its estimate. It was the first time the piece had been at auction, having remained in the same family for decades.

Even Haute Époque, which I had thought was a declining market, is having a moment, according to auctioneer Alexandre Giquello. He also thinks this is because of collectors acquiring medieval and Renaissance properties. ‘There is a new interest in Kunstkammer objects,’ he says, citing a 14th-century ivory diptych, which he sold for four times its estimate at €40,040, and a Limoges enamel from c. 1560, which made a within-estimate €13,000.

De La Forest Divonne concludes: ‘There are still many discoveries to be made in France, but often it’s not in the salons but in the attics that we find things.’

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.