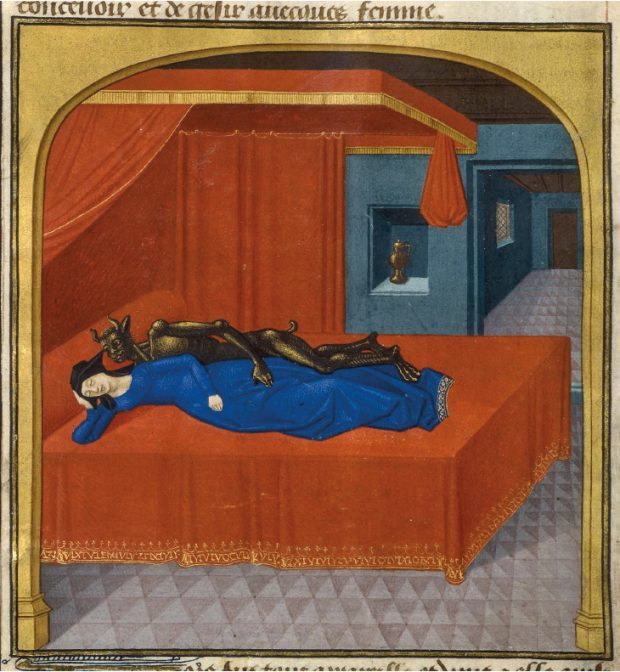

From infant soothsayer to besotted old man, Merlin is an unwieldy figure in the history of medieval art and literature, whose influence echoes into the modern age. His character takes its first recognisable form in the first half of the 12th century in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) and was inspired by Myrddin Wyllt, the mad poet and seer of Welsh legend. Geoffrey’s was the definitive history of Britain until at least the 1400s, full of appealing nuggets that were retold in the vernacular soon after its composition. Among them is the tale of Merlin’s conception, which took place when an incubus visited his mother in the night. In one 15th-century illustration of a French Estoire de Merlin (a 13th-century life of Merlin derived from Geoffrey’s Historia), the demon embraces her sleeping form, a clawed hand preying on the V-folds of her virginal blue dress.

Contemporary readers may have been curious about the motives of the amorous demon. By the time of the later Estoire, its advances are the culmination of a diabolical scheme to undo Christ’s work on earth. Indeed, the tale plays off that of Christ’s Incarnation and its marvellous consequences. Whereas the divine half of Christ’s parentage leaves no visible trace, Merlin is born covered in hair. As an adult, he is able to change his own form and that of others. In one instance he appears before Julius Caesar as a stag with a white forefoot to announce his later arrival in the form of a Wildman; in another he makes Uther Pendragon look like Gorlois of Tintagel, a Cornish noble, so he can sleep with Gorlois’s wife, whereby they conceive Arthur. Nevertheless and despite the best laid plans of the infernal legion, Merlin’s powers are never directed to the damnation of mankind.

Detail showing a demon visiting Merlin’s mother in the night, from the ‘Lancelot-Graal’ (Ms Fr. 96), illuminated by the Master of Adelaïde of Savoy, Poitiers, France. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

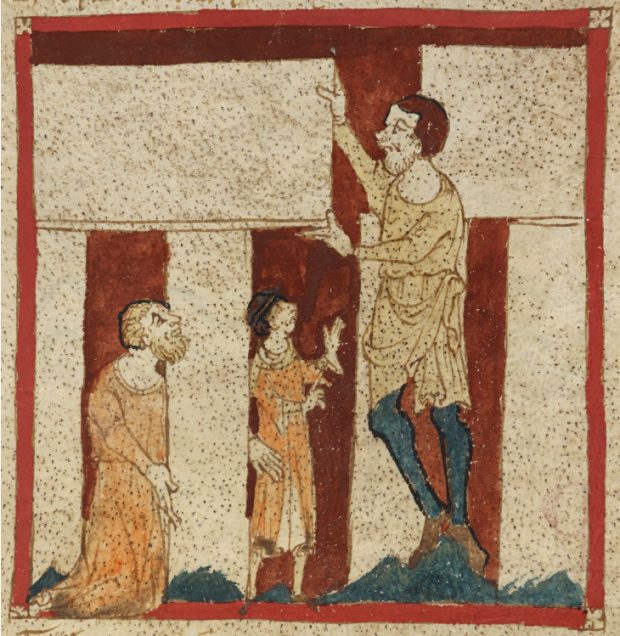

According to Geoffrey, Merlin is only a child when he is found by the usurper, King Vortigern. Asked why his half-built tower keeps crumbling, Vortigern’s soothsayers tell the king the problem will abate if he sacrifices a boy with no human father. Sent out in search of the child, the king’s men discover Merlin, who, begotten by an incubus, fits the description, in Wales. They bring him to Vortigern, who, Merlin says (saving himself), should have a pit dug by the tower. In it they find a red and a white dragon fighting with earth-trembling force. These are interpreted by Merlin as a symbol of the coming conflict between the Britons and the Saxons.

In Geoffrey’s Historia the discovery of the dragons is followed by the young Merlin’s surreal prophecies regarding the kings of Britain. These were incorporated into the Historia from an earlier work by Geoffrey. On the whole, they are teasingly non-specific, comprising a string of animal metaphors that can be interpreted as political figures. I remember hearing Paul Russell, a professor of Celtic, compare the style of the Prophetie Merlini (‘within Winchester shall the hedgehog hide his apples’) with that of Humphrey Lyttleton’s closing remarks on the BBC Radio 4 programme ‘I’m Sorry I haven’t a Clue’ (‘and so, as the little Andrex puppy of time scampers on to the busy dual carriageway of destiny…’).

For several centuries after Geoffrey, Merlin was best known in England as a post-biblical prophet whose proclamations had a direct bearing on the history and future of the land. They were copied and commentaries were added, which was standard practice in the Middle Ages for authoritative texts such as works of Classical poetry or the Psalms. On the opening page of one annotated copy of the Prophetie, the text in black ink in the lower left corner has two sizes of script running in parallel. The larger is the text proper and the smaller is the interlinear commentary, which interprets the Prophetie in the light of contemporary political events and the reigns of recent kings. At least four surviving copies open with a frontispiece showing King Vortigern and Merlin. The child is often shown with a scroll to denote the eternal import of his words.

It is important to remember that modern distinctions between forms of the supernatural should not be projected on to the Middle Ages: Merlin was not a ‘wizard’ in today’s sense. Monks read and interpreted Latin texts with commentaries like these, which makes it intriguing that two versions of the image of Merlin prophesying to Vortigern (Cambridge University Library Ff.1.27 and Cotton MS Julius A V) show the young seer with a tonsure and wearing a monastic habit. These images emphasise the political value of Merlin’s deep learning and associate it with the contemporary clergy.

One of Merlin’s greatest feats shaped the mythic topography of Britain. It concerns the earliest origins of Stonehenge, a monument shrouded in the mystique of antiquity, even to Geoffrey, who situated Merlin’s activities just after Roman occupation of Britain, hundreds of years before his own time. According to the Historia, Vortigern massacres a group of Britons in Amesbury. The rightful king, Aurelius Ambrosius, uncle of King Arthur, kills Vortigern by burning him to death in his own tower and reclaims the throne. To commemorate the fallen Britons, Aurelius sends his men to dismantle the so-called Giants’ Dance in Ireland, brought from Africa by giants, and rebuild it on the site of the massacre. Merlin, still a child yet capable of marvellous feats of engineering, enables the men to move the heavy stones, ‘thus proving that his artistry was worth more than any brute strength’. A 14th-century miniature in a copy of Wace’s Roman de Brut (a vernacular verse translation of Geoffrey’s Historia) shows the child guiding their deconstruction, his cerebral mastery of giant forces stressed by his small stature.

Detail showing the child Merlin dismantling Stonehenge, from the ‘Roman de Brut’ by Wace (Egerton MS 3028), c. 1338–40, England. British Library, London. Photo: © British Library Board. All rights reserved/Bridgeman Images

At the end of the First World War, Stonehenge was given to the nation by Sir Cecil Chubb. The prevailing hypothesis of the time, that it had been built to service a prehistoric sepulchral cult, accounts for a report published in November 1918 in the Salisbury and Winchester Journal and General Advertiser: the acquisition of Stonehenge for the nation ‘invested it with an additional solemnity with regard to the fallen in the war’, and (fascinatingly given the medieval legend) it was ‘one of the most splendid memorials of the kind that anyone could imagine’. Merlin’s presence may be felt in the next section of the newspaper report, which relates the response of the ‘Latter-day Druids’. Their movement can be traced back to the neo-Druidism of the 18th century, explored in the writings of the eminent neoclassical architect and Christian fundamentalist John Wood (who was responsible for much of Georgian Bath). Architectural historian Eileen Harris has shown that Wood rejected the notion that the classical forms he used for his own buildings originated in ancient Greek and Roman contexts, claiming they were stolen from ‘the Hebrews’. He came to believe that Stonehenge had been a Druidic site of worship and that the British Druids had received their religion from Phoenician traders, soon after the building of Solomon’s Temple. Subscribing to Geoffrey’s story of the ancient line of British kings, Wood believed that the Merlin associated with Stonehenge preserved the memory of a real Archdruid.

Throughout the later Middle Ages, the figure of Merlin had the ability to fascinate on both sides of the Channel, although he was of less political significance beyond English contexts. The Estoire de Merlin was part of an influential vernacular retelling of the Merlin legend, which included the story of the Holy Grail and the romance of Lancelot and Guinevere, known collectively as the Vulgate Cycle. It is thought that a lost version of the Estoire was an important source for Le Morte d’Arthur, by Sir Thomas Malory (c. 1415–71), which makes the recent discovery of a unique variant of the Estoire an exciting new development in the history of Arthurian scholarship. It was found in the special collections of Bristol Central Library, who identified names including ‘Artu’, ‘Gawain’ and ‘Merlin’ in the text of seven 13th-century parchment fragments being used in the binding of four late medieval printed volumes.

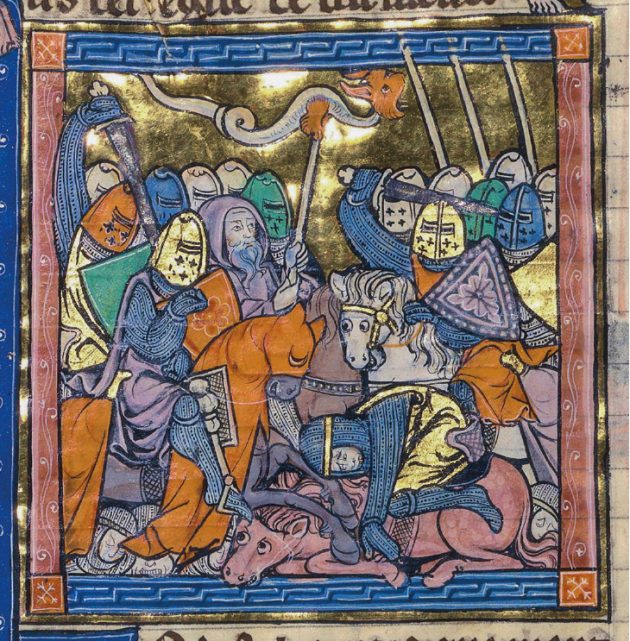

The part of the story preserved in the Bristol fragments concerns the adult life of Merlin, beginning with King Arthur, Merlin and Sir Gawain as they prepare for battle against King Claudas at Trèbes, in southern France. Claudas is a fictional Frankish king who occupies a kingdom called the Terre Deserte. (The name echoes the motif of the ‘wasted land’; a territory ruled by an impotent king, destined to be saved by a hero and indirectly the source for T.S. Eliot’s poem of 1922.) Merlin leads Arthur’s men into battle under Sir Kay’s standard, a kind of automaton taking the form of a fire-breathing dragon. While the Bristol fragments have no illustrations, a contemporary French depiction of the same moment shows Merlin as a hoary old man in a grey-hooded cloak, placidly waving the pyrotechnic dragon in a sea of helms and shields. Again, Merlin facilitates political change while adding a gloss of the miraculous.

Detail showing Merlin leading Arthur’s men into the ‘Roman arthuriensis’ (MS Fr. 95), 1270–90, France. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

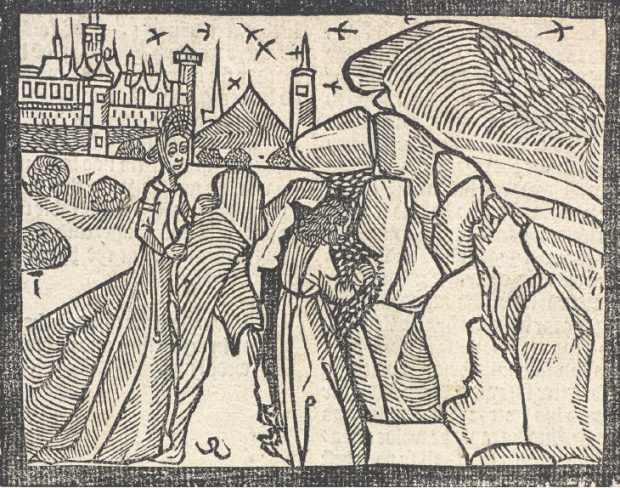

The seer’s death is unaccounted for by Geoffrey of Monmouth. In the later Estoire, however, he is effectively murdered by Vivien, one of the Ladies of the Lake. The Bristol fragments have Merlin stay with her for a week to teach her the art of putting others to sleep, during which time he falls in love with her. In the more cohesive Post-Vulgate Cycle (a 13th-century revision of the Vulgate Cycle), she is the agent of Merlin’s demise, driven by hatred to lure him into a sealed tomb. In Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, Vivien has no other way of shaking off a sinister old stalker:

And always Merlin lay about the lady to have her maidenhood, and she was ever passing weary of him, and fain would have been delivered of him, for she was afeard of him because he was a devil’s son, and she could not beskift him by no mean. And so on a time it happed that Merlin showed to her in a rock whereas was a great wonder, and wrought by enchantment, that went under a great stone. So by her subtle working she made Merlin to go under that stone to let her wit of the marvels there; but she wrought so there for him that he came never out for all the craft he could do. And so she departed and left Merlin.

The moment of Merlin’s entrapment is illustrated by a woodcut print in Wynkyn de Worde’s 1498 edition of Malory’s text, accompanied by the rubric, ‘How Merlin was assoted and dooted on one of the ladyes of the lake and how he was shette in a roche under a stone and there deyed.’ The variety of marks made by the cutter’s gauge, from long scoops, to lines and dots, fosters a chaotic atmosphere. Birds, oddly reminiscent of aeroplanes, take to the air around Camelot and what may be the Isle of Avalon in the conical guise of Glastonbury Tor. At the dark heart of the image, Merlin ventures into his deathtrap, his eyes wide, his hands outstretched. Vivien, who looks out at the viewer with a knowing smile, seems to grow from the rock itself, her skirt shaded with the same pattern of lines as the adjacent stone. Pupil outsmarts the master and he is neither seen nor heard from again.

Illustration of Vivien tricking Merlin into entering the cave in Le Morte d’Arthur (1498) by Thomas Malory, published by Wynkyn de Worde. University of Manchester Library. Photo: © University of Manchester

The scholar Carolyne Larrington notes that the fall of a venerable old man at the hands of a young femme fatale is a trope reflected in another medieval cautionary tale. It concerns the philosopher Aristotle and Phyllis, the mistress of Philip II of Macedon. Her seductive powers hold the aged intellectual in such thrall that he allows himself to be ridden side-saddle. A Southern Netherlandish bronze aquamanile (pouring vessel) of the late 14th or early 15th century shows the bare-shouldered dominatrix perched side-saddle on the sage, her left hand (the ‘butt’ of the vessel’s handle) resting on his backside, while her right seizes a tuft of his receding hair. The long points of his shoes flatten against the ground, at once elegant and pathetic. The object would have been used for the washing of hands, perhaps at a feast. It is possible to imagine noble women exchanging knowing glances while venerable men feigned submission in a parody of misrule.

Merlin and Vivien is one of the 12 narratives in Alfred Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (1859–85), the action for which was derived chiefly from Le Morte d’Arthur and the Mabinogion (a collection of stories set in the ancient British past). Tennyson’s Vivien is a young and canny seductress, who erodes Merlin’s resolve until he provides her with the means to place him in a death-like sleep:

Then, in one moment, she put forth the charm

Of woven paces and of waving hands,

And in the hollow oak he lay as dead,

And lost to life and use and name and fame.

Then crying ‘I have made his glory mine,’

And shrieking out ‘O fool!’ the harlot leapt

Adown the forest, and the thicket closed

Behind her, and the forest echoed ‘fool’.

The Beguiling of Merlin (1872–77), Edward Burne-Jones. Lady Lever Art Gallery, Liverpool. Photo: © National Museums of Liverpool, Lady Lever Art Gallery

Vivien’s triumph is represented by Edward Burne-Jones in The Beguiling of Merlin (1872–77). The sage’s face is clean-shaven and his features delicate, even feminine. Reflective tears or some gleam of prophetic sight, if only of his own doom, obscure his pupils. Vivien disables Merlin physically and cerebrally, turning her face back towards her quarry, her eyes glittering and the muscles of her neck strikingly exposed. The historian Stephanie Barczewski argues that, to the Victorian mind, Vivien embodied the threat of prostitution, which sought material reward for sexual favours and undermined the domestic foundation on which Britain’s international success was believed to rest. In Ralph Macleod Fullerton’s version of the tale, Merlin: A Dramatic Poem (1890), an internal monologue reveals her true, gender-flouting ambition: ‘Vivien shall be King!’. The gravity of her crime depends on the particular nature of Merlin’s unstable corporeality, so often depicted at the weakened poles of life – in childhood or dotage – in contrast with his ageless mind.

In art and legend Merlin flickers between human and non-human, court and forest, testing the boundaries of the body, gender and society. His malleability has led to the use of his character as a vessel for a range of political and religious opinions. Merlin is, perhaps, a puritanical personification of the human intellect: capable of wonders, born of the devil, vanquished by sex.

From the April 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.