Georges Rouault was born in a cellar during the Paris Commune uprising of 1871. His mother had fled underground seeking refuge from explosives. After his birth, she nicknamed him ‘Obus’, meaning artillery shell. Rouault later lived through both world wars and experienced recurring bouts of physical illness and psychological strain. Despite a secular upbringing, an ‘abyss’ of sorrow and solitude led Rouault to convert to Catholicism at the age of 24 – doubling down on faith in a time when many questioned how God could allow such suffering.

It was faith not only in God, but in ambiguity – the belief that suffering might have a reason, even if it remains obscure. Rouault felt compassion for the underprivileged, the wretched and the damned. An exhibition organised by Skarstedt in collaboration with Shin Gallery, the first in New York since a retrospective at MoMA in 1953, displays the full range of his empathy. His favourite subjects, aside from religious ones, were prostitutes and professional clowns – figures firmly on the margins of society. His paintings seem to include every layer that complicates a person’s life: sometimes creating a finely delineated portrait, at other times an indecipherable mess.

Pierrot (c. 1937–38), Georges Rouault. Courtesy Shin Gallery, New York/Skarstedt, New York; © 2025 Estate Georges Rouault/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The paint in one Pierrot portrait is so densely layered that Rouault seems to have reworked it endlessly atop previous drafts. The forlorn clown faces us with blacked-out eyes and a small mouth. You can feel the artist’s concern for his subject, but, by the final coat, nearly all life is lost in a game of telephone between the layers of paint. Pierrot’s face sags like a lumpy potato, his arms are stiff as logs and the surface of the painting is like a grainy rock face. Rouault has painted the picture to death.

Rouault never released a painting from the studio unless he considered it fully resolved, which could take years. Some paintings in the Shin/Skarstedt show have dates that span as much as a decade. He burned more than 300 canvases that he thought would never reach completion, displaying a sense of perfectionism that was at odds with his tolerance of imperfections in others.

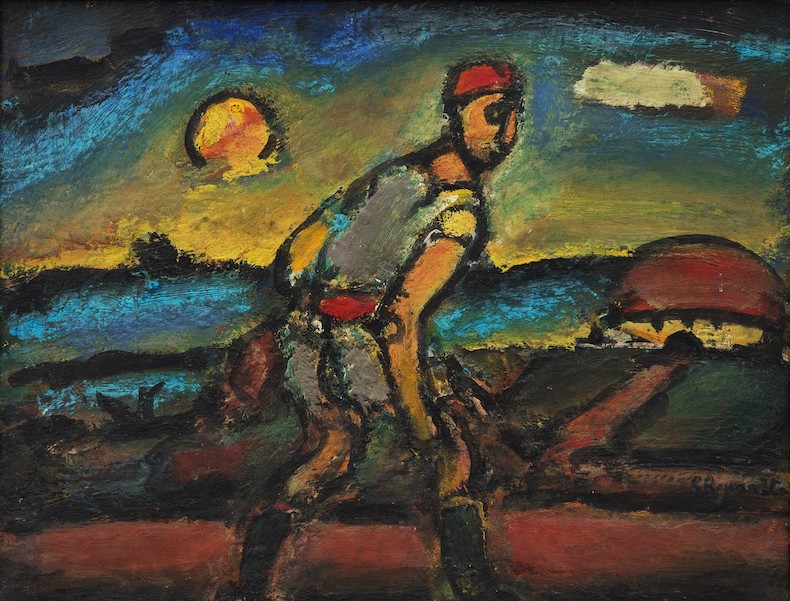

Trained by the Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau, Rouault saw his subjects as walking allegories, waiting to be captured in paint. In Le Fugitif (1945–46), a man on the lam sidles across a brooding landscape. He makes himself small – hunched over, looking back at us over his shoulder – but still towers over the horizon with wind and clouds swirling around his head. His orange face bellows with anxiety against an eerie yellow and green sky. Rouault paints his subject less as a criminal and more as a victim of circumstance. Perhaps the fugitive is fleeing not just the law, but his own nature.

Le Fugitif (1945–46), Georges Rouault. Courtesy Shin Gallery, New York/Skarstedt, New York; © 2025 Estate Georges Rouault/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Rouault goes a step further in his portraits of Satan. In the small canvas at Shin/Skarstedt, Satan’s face almost fully fills the composition, a choice that that foregrounds his personality rather than his evil powers. Smooth wet outlines soften his cheeks – as though Rouault has caressed his face with each brush stroke (as if to say ‘there, there’) until his malevolence is washed away – or covered up – by successive applications of paint. Satan’s understanding expression suggests that he might even be tearing up. He’s not evil on purpose; it’s just that his impulses sometimes get the better of him.

The only people Rouault treated without sympathy were judges – a subject he returned to again and again. ‘The reason I gave my judges such woeful faces,’ he said, ‘was doubtless because I expressed the anguish that I myself feel when I see one human obliged to judge another.’ One work here depicts two judges dressed in satanic red robes facing each other in profile. Their beards look like the jawbones of a skull – perhaps mocking the idea that they should pass judgement on anyone living.

Deux juges (Two judges), (1937), Georges Rouault. Courtesy Shin Gallery, New York/Skarstedt, New York; © 2025 Estate Georges Rouault/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Rouault kept Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal by his bedside and even read it to his children as a bedtime story. He created a series of illustrations and paintings in response to these poems about the corruption and seductions of modern life. One such work portrays a woman – possibly a prostitute, one of Baudelaire’s recurring figures – with sickly olive skin, wearing only red socks. Her body curves into a C-shape as she reaches across herself to clutch her face in agony. She glances off to the side as if wondering whether a different life might have been possible. We are entitled to ask God for an explanation, Rouault seems to say, but it might be too much to expect that we will understand.

‘Georges Rouault’ is at Shin Gallery in collaboration with Skarstedt, in New York, until 12 July.