Gerhard Richter first visited Sils in the Upper Engadin valley in 1989. He was to return, over summers and winters, for more than 25 years, until he was in his early 80s and could no longer hike. The diverse body of work that evolved out of his engagement with this remarkable Alpine landscape has now been assembled for the first time and is being exhibited across three venues in the area – the Nietzsche-Haus (in Sils Maria), the Segantini Museum and Hauser & Wirth (both in nearby St Moritz). The curator of this loan show is Dieter Schwarz, a former director of the Kunstmuseum Winterthur and the author of the catalogue raisonné of Richter’s drawings – and the friend who first introduced the artist to the Engadin.

That the 70 or so paintings, drawings, overpainted photographs and objects here are not landscapes in the conventional sense should not come as a surprise to anyone who knows Richter’s work. He began painting landscape motifs from his own photographs back in the late 1960s, his most significant subjects – mountains and the sea – the very staple of the Romantic landscapes of his countryman Caspar David Friedrich. Such unfashionable subject matter ran counter to prevailing notions of contemporary art.

At the time, Richter said that his images were ‘not only about beauty, nostalgia, romanticism or classicism, like some paradise lost, but that they were mostly “dishonest”’ in the sense that they glorified nature. He had experienced enough of sea and mountain to understand that so-called Mother Nature was ‘always against us in every form’. Yet what is most striking about these images is the very absence of spectacle, the denial of the sublime. This negation is made all the more apparent in these Alpine exhibition spaces, where the view from every window is spectacular. Moreover, even where a rare figure is included, such as in Schlucht (Ravine) from 1977, there is a sense of detachment, dislocation, of the figure at one remove. If there was a narrative thread, it is broken. This art may be personal, but it is not anecdotal.

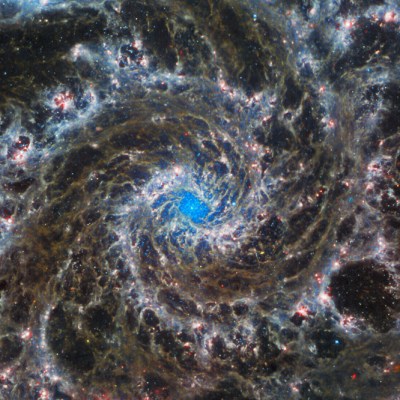

Silsersee, Maloja (Lake Sils, Maloja) (1992), Gerhard Richter. Private collection, Switzerland. Photo: Jon Etter; © 2023 Gerhard Richter

Richter’s process is key to understanding his intentions. At Hauser & Wirth, the colour photograph used for St. Moritz helpfully hangs alongside the finished work (1992). To produce the painting, in his studio in Cologne, the artist first projected an image of the photograph on to the canvas, drawing lines to mark out and adjust the composition. As for the imagery itself, as Schwarz notes in the catalogue, Richter’s choice of motifs was never immediately obvious even to himself: a corner of a nondescript building, trees, snowdrift, path. The painted image was blurred with a soft brush, erasing both immediacy and traces of reality. In Waldhaus (2004), the landscape has been similarly muffled and flattened to a two-dimensional wall of a forest topped by a band of mountain ranges. What is left is the mood of a place, a distant memory. Perhaps it is relevant that the Engadin reminded the artist of the countryside of his childhood in Upper Lusatia, close to the Polish border.

These are paintings devoid of painterly gesture. Richter’s choice of the mechanical – the artificial eye of the camera – and the further reproduction and diminution of the motif in his works suggests the inaccessibility of the sublime – and God – in our post-industrial age. Giovanni Segantini (1858–99), painting his great Symbolist triptych Life-Nature-Death en plein air in direct response to the mountains, displayed here under the museum’s chapel-like dome, had no such doubt.

In contrast to the paintings and the elegiac, poetical pencil drawings on pigment print, both titled Sils (2015), Richter’s painted photographs seem positively upbeat and playful. Whenever the artist made paintings using photographs, he would always mark them with colour notes. Realising these dabs were interesting in their own right, he began to experiment. The photographic image is at times spattered with oil paint, at others almost annihilated. Thick disguising layers are abstracted by squeegee, or surfaces enhanced by boldly coloured and richly textured impressions, occasionally formed by pressing one image on top of another in a nod to Max Ernst’s use of decalcomania. Richter plays with quasi-realistic snowflakes in blue and pink or red, and offers branches laden with snow-white pigment or leaf-green ‘foliage’. Here are traces of the picture-postcard Engadin absent in the paintings – skiers, villages, valleys.

St. Moritz (1992), Gerhard Richter. Private collection, Switzerland. © 2023 Gerhard Richter

Always tentative about revealing new work, Richter first unveiled a selection of these painted photographs in 1992 for a modest show at the Nietzsche-Haus, where the philosopher summered between 1881 and 1888, and which was later turned into a museum. Curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, it was accompanied by an artist book, Sils, for which the artist further abstracted and manipulated his images. For this event, Richter also produced an edition of a matte stainless-steel sphere which he had in his studio and which, when rolled, would set in motion reflected hues of his paintings and their surroundings. Their elusive, gleaming surfaces allow no access. Each of the Kugeln in the edition bore the name of a local mountain. One of them now returns to the floor of Nietzsche’s simple wooden bedroom. These orbs are the leitmotif of the show; another two are displayed at the Segantini Museum and at the Hauser & Wirth gallery.

Ever since opening the St Moritz space in 2018, Iwan Wirth has nurtured his idea of exploring Gerhard Richter’s relationship with the Engadin. This exemplary show has been well worth the wait.

‘Gerhard Richter: Engadin’ is at the Nietzsche-Haus, the Segantini Museum and Hauser & Wirth St. Moritz until 13 April 2024.