From the January 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

After Géricault died, Ingres irritably petitioned that The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19) should be removed from the Louvre. ‘Art must only be about beauty,’ argued this militant classicist, not ‘the cadaver of mankind’. It is true that Géricault’s art is seldom lovable: nothing in it is merely decorative, nothing panders to canons of aesthetic propriety and there is little romantic grandiosity in it either. It moves restlessly between all genres except landscape; it resists definition – if Géricault himself is to be assigned to any category, it should be that of the realist. His fascination with the violent and the extreme meant that he never looked away or edited out the ugly; his eye for the vagaries of street life was as quick and unsentimental as that of a modern photojournalist; his portraiture of both humans and horses has a psychological acuity that can make the smoother surfaces of David and Ingres look merely bland. The Raft of the Medusa may now be recognised as a stupendous feat of imagination in terms of its composition, but it was also meticulously researched in its detailing, rendering faithfully even the precise gaps between the raft’s timbers.

Two hundred years on from his death, at the age of 32, an aura of Byronic mystery shrouds Géricault’s biography. Contemporaries found him disturbingly unreadable and charismatic. A beautiful young man with almond eyes, something of a dandy, but mercurial in his moods with a tendency to pick nasty fights, he might today be diagnosed as manic depressive. He travelled only to Italy and England, but his was a ceaselessly restless and troubled existence. His English friend, the architect C.R. Cockerell, describes him ‘lying torpid days and weeks, then rising to violent exertions […] tearing driving exposing himself to heat and cold violence of all sorts’. His sexual life is intriguing. A secret affair with Alexandrine, the young wife of an uncle who had generously sponsored his studies, was tormented and guilt-ridden. After giving birth to his son, Alexandrine left the marital home and became a recluse. Géricault would never see her again, and perhaps never saw the boy at all. Was it this tragedy that precipitated his several reported suicide attempts? Other questions linger. What should we make of the erotic charge in his studies of the male nude – a quality signally absent from his (rare) depictions of women, clothed or unclothed? What was the nature of his stormy relationship with his teenage assistant Louis Jamar, who lived with him in close quarters throughout the gestation of The Raft of the Medusa? Surviving letters are unrevealing and much of what is known comes from unreliable posthumous recollection. There are still crucial gaps in the record.

A Horse Frightened by Lightening (c. 1813–14), Théodore Géricault. National Gallery, London

Born in 1791 in Rouen, Jean-Louis-André-Théodore Géricault came from a solidly bourgeois family: his father was a lawyer turned accountant, his mother had wealth inherited from tobacco manufacture. Having kept clear of Revolutionary turmoil, they prospered in the Napoleonic era and moved to Paris, sending Théodore, their only child, to the prestigious Lycée Impérial. Beyond a talent for drawing, he evinced no academic bent. But he was passionate about horses – his greatest pleasure, according to his cousin, being ‘to gallop wildly through the countryside, preferably mounting pure-blood horses and always selecting the wildest ones’. Evading parental pressure to train for a profession (and with the financial help of the uncle he was later to cuckold), he sought to combine his talent with his passion by entering the studio of Carle Vernet and learning the craft of equestrian painting. But Vernet’s paintings are inert and mediocre things compared to Géricault’s. Influenced by the British school led by Stubbs, Vernet painted horses with clinical accuracy, depicting them calmly controlled by their grooms or marked as someone’s property. Géricault, on the other hand, felt their rearing, whinnying, thunderous energy, their soulful intelligence. Vernet saw horses as objects, at best trophies; Géricault understood them as sensitive beings and for the rest of his creative life they remained a persistent obsession, rendered as if from the inside rather than externally observed.

Study of a horse from Théodore Géricault’s sketchbook (1812–14). J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The variety of treatment is astonishing. Two of his first mature canvases, the Charging Chasseur exhibited at the Salon of 1812 and the Wounded Cuirassier from two years later, are battlefield images in which the steeds are presented as heroic warriors. From Géricault’s sojourn in Rome come thrillingly animated sketches of the Race of the Barberi, in which Arab thoroughbreds were forced to gallop bareback down the Via del Corso – the Romans’ efforts to goad them at the beginning and restrain them at the finishing line fascinating him equally. A painting in the National Gallery shows a stallion quivering with fright at a stroke of lightning, its every sinew stiffened as though electrified; in the Louvre, the head of a white horse radiates a sweet melancholy, its forelock gently brushed over its eye. There are hundreds of quiet studies and affectionate watercolours too – of stabled horses, pawing the ground, feeding and twitching, and dray horses drawing heavy carts, and farmyard nags patiently being shod at the farrier’s or trotting out for exercise. Philippe Grunchec has claimed that Géricault ‘revitalised the European vision and pictorial representation of the horse’. One might go further and claim that in this field he has never been surpassed.

Perhaps Géricault was more ambivalent about the human than he was about the equine. Never eager to please, he executed very few conventionally posed ‘society’ commissions, even though he clearly had the technical skill to do so and his doodles are full of quick pencilled profiles. Two series of finished canvases, however, present striking portraits that defy easy interpretation. The first consists of images of children of perhaps five or six, mostly identified as the offspring of his friends, painted in a style and palette unlike anything else in his oeuvre. Posed against dark rocky landscapes, the physical proportions of the figures seem slightly doll-like – their heads too big for their bodies, their postures uncomfortable. Their facial expressions are thoughtful, but charmless and even sceptical: these infants are dangerous unknown quantities, free from any parental supervision, but in no mood to play.

Alfred Dedreux (1810–1860) as a Child (c. 1819–20), Théodore Géricault. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

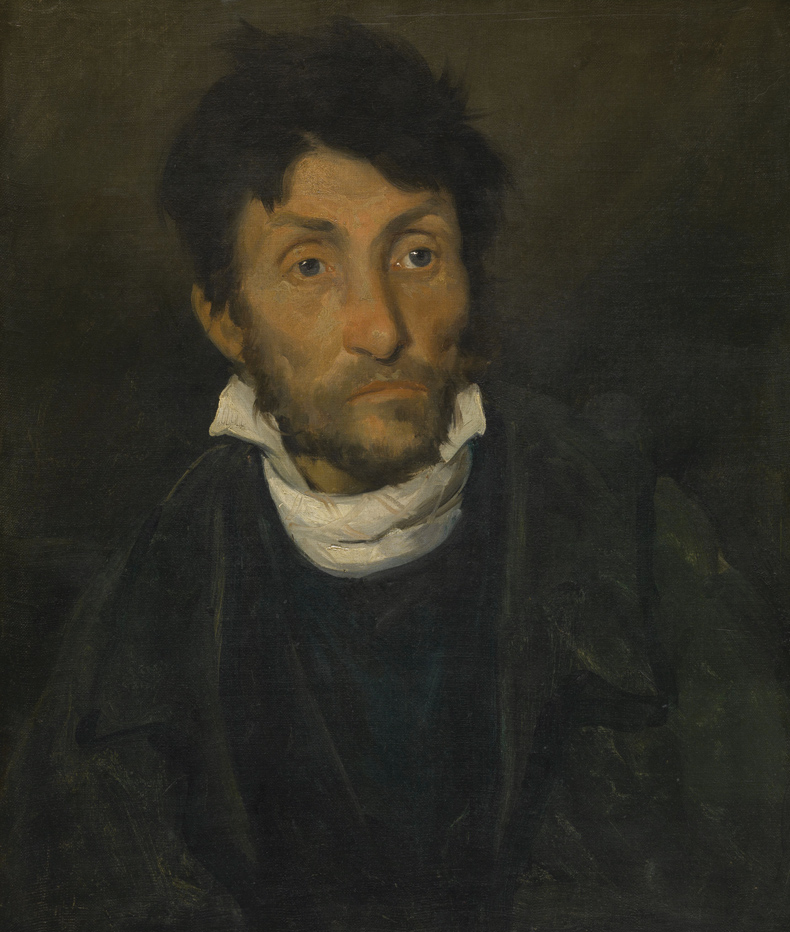

Even more troubling are the portraits of the insane that may or may not represent Géricault’s final great endeavour. But they cannot be dated with certainty. Indeed, almost everything known about them dates from 40 years after the painter’s death, when in 1863, five canvases were discovered by the art critic Louis Viardot in an attic in Baden-Baden belonging to a Dr Lachèze. According to Viardot, these represent the surviving half of a series of ten – the other five already lost and never recovered – painted for the pioneering psychiatrist Étienne-Jean Georget, and then inherited by his pupil Lachèze. Strangely, however, Georget had vigorously denied that facial expression could be a significant factor in diagnosing mental disorders – something which the portraits so hauntingly seem to reflect – and had proposed instead that they were the result of brain lesions. So what clinical purpose, if any, the portraits may have had is also unclear. It has been suggested that Georget may have treated Géricault for melancholia and that the paintings served as payment, but there is no firmer evidence for this than there is for ascribing various monomanias to the individuals depicted – this was Viardot’s doing, perhaps based on what Lachèze had been told.

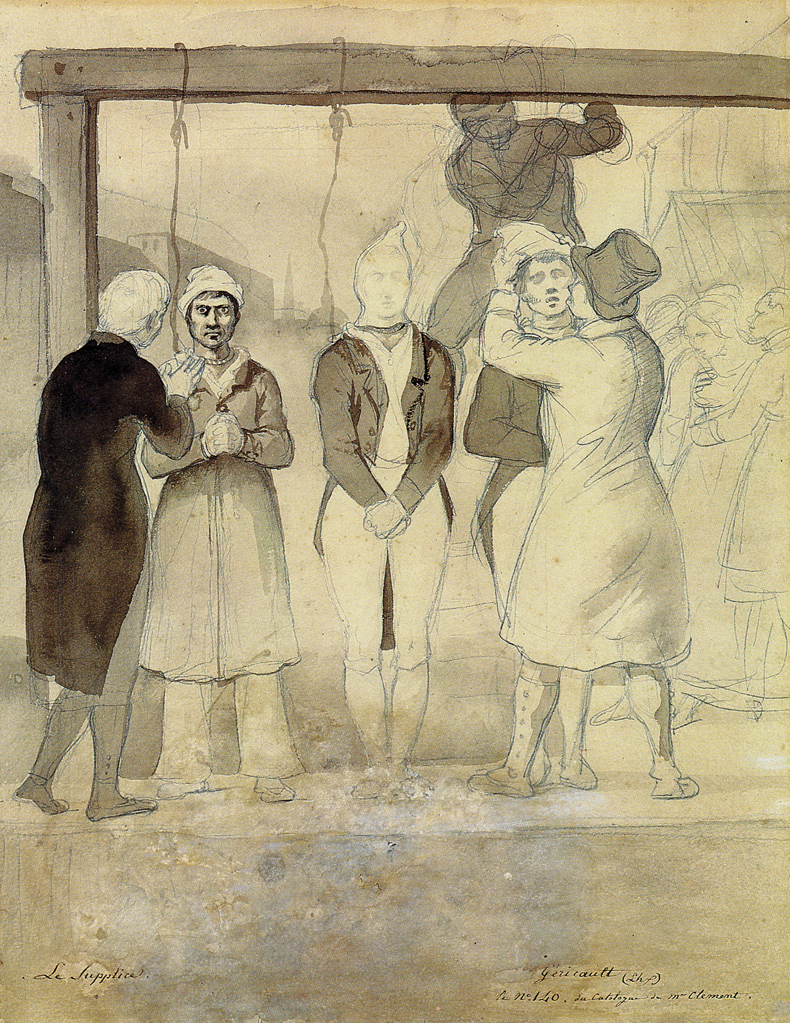

But the intensity of the portraits accords with Géricault’s ability to focus his gaze unsparingly on aspects of life from which others shied away: he was ready to contemplate rotting corpses and guillotined heads, and even the unimaginable horror that might be felt seconds before certain death. He must have been there when the Cato Street conspirators were executed for treason in London in 1820: his pen and ink drawing eerily captures the absolute terror in the eyes of William Davidson, the mixed-race son of the attorney general of Jamaica, as he receives the ministrations of a priest and awaits the fatal drop into oblivion.

Scene of a Hanging in London also known as The Hanging of Arthur Thistlewood and his Accomplices (1820), Théodore Géricault. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen. Photo: Réunion des Musées Métropolitains

This wasn’t fashionable Gothick sensationalism: Géricault may have been morbid, but he was no fantasist dealing in cheap thrills. As a monograph of 2010 by Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer explores, he had a sincere social conscience that informs much of his art, aligning him during the post-Napoleonic era of the Restoration with the reformist liberal persuasion. His views did not manifest themselves in overt activism or commitment: it is rather in his choices of subject that his sympathies become evident. For example, in the crippled veterans cashiered after the defeat of the Grande Armée and left to turn to beggary; or the West African victims of France’s involvement in the slave trade; or the scenes from the Latin American wars of independence; or the desperate poor of London.

Nowhere, however, was his attitude expressed with more dramatic force than in The Raft of the Medusa. The appalling episode it represents – the starvation, drowning and cannibalism that ensued after the French naval frigate Méduse ran aground on its way to Senegal in 1816 – has often been told, notably in Julian Barnes’s History of the World in 10½ Chapters. But the lengthy planning that Géricault’s epic painting entailed also illustrates the hard-headed aspect of his personality: The Raft of the Medusa was designed with a clear intention of scoring commercial success, by an artist who was furiously competitive yet determined to do things his way. Géricault wouldn’t stoop to flattering society ladies or churning out scenes that conformed to academic codes, but he knew what the public wanted – and that included spectacular shipwreck scenes, as marketed by John Singleton Copley and others.

Portrait of a Kleptomaniac (c. 1820–24), Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent

For 18 months he worked on realising his vision in conditions of monastic simplicity and total silence, his expression one of ‘perfect calm’ as his friend Antoine Montfort recalled. The initial response to the result was bitterly disappointing. The Salon of 1819 awarded the painting one of 34 gold medals, but the critics found it too gruesome, too monochrome, too heedless of the conventions. Dismayed but undaunted, Géricault decided to roll up the canvas and transport it to London, where he signed a deal with William Bullock, owner of the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly. The audience here might have been less sophisticated than that of Paris, but also more open-minded, and Bullock could market The Raft of the Medusa for admission at one shilling, on a par with entertainments such as dioramas, peep shows and demonstrations of electrical phenomena. The scheme was a success – 50,000 visitors paid up over six months and there were big profits for all concerned. Jerricault (as his name was anglicised) was lionised about town and embarked on a series of lithographs which promised him ‘fortune considérable’. He seems to have enjoyed the trip. How much credence can be given to his travelling companion Nicolas Charlet’s report, made 30 years later, that he had discovered Géricault unconscious in his London hotel room after another botched suicide attempt?

Study of the Model Joseph (c. 1818–19), Théodore Géricault. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Back in France, Géricault’s last years certainly seem to have been miserable. He lost almost all his money in the stock market and his health, never good, went into terminal decline when a riding accident left him with a painful abscess on his spine. After he impulsively lanced it with a larding needle, the infection spread. To the despair of his friends, he wasted away for three agonising months. Delacroix – seven years his junior, and a more unambiguously Romantic spirit – visited him on his death bed and reported that ‘his thighs are as thin as my arms’. When someone mentioned The Raft of the Medusa, Géricault spluttered ‘Bah! Une vignette!’, turning his fevered mind instead to plans for grandly scaled paintings on contemporary themes such as the Greek War of Independence and an outbreak of plague in Barcelona. He died early in 1824; his wretchedly gaunt death mask can still be seen in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in his native Rouen. The Louvre subsequently acquired The Raft of the Medusa for a measly 6,000 francs – a tenth of what it was prepared to pay for more polite work by David and Ingres – and through the 19th century, his reputation waxed and waned according to the political climate. On the bicentenary of his death, his restless complexities and rough edges make him seem thrillingly and vividly modern. Yet the enigmas remain: we must know barely half his story.

From the January 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.