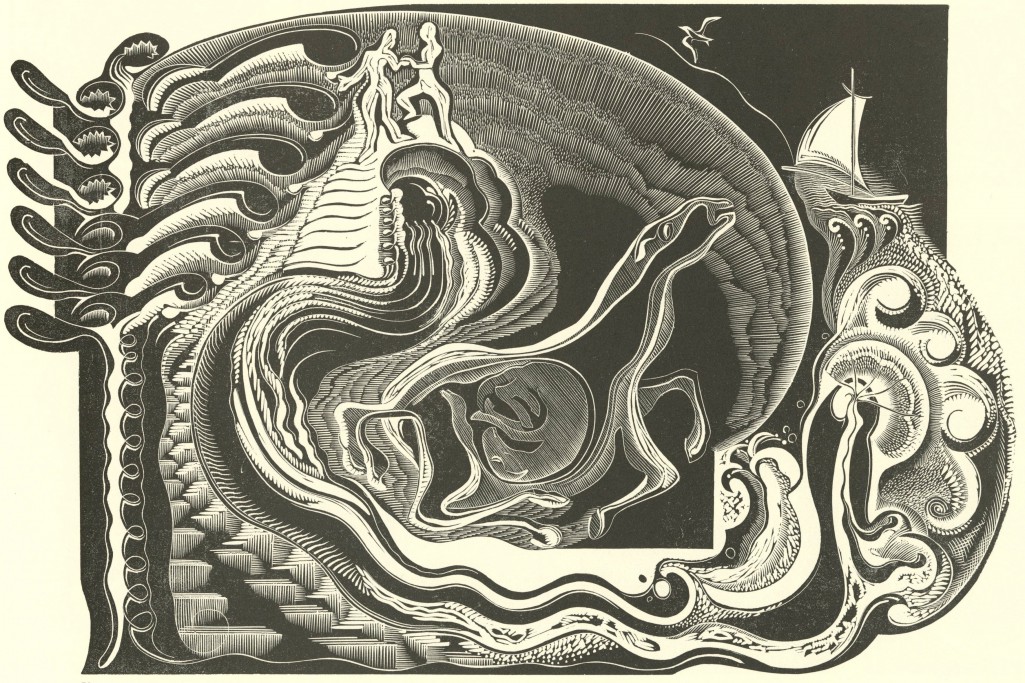

In her wood engraving One Person (1937), Gertrude Hermes shows a swimmer striking out across a whirl of water, the angle tilted as though to suggest a fall. The woodblock had originally been used for Autumn Fruits (1935). It was later shaved down to make space for Welcome to the Avocets (1948). Far from striving to leave her mark on the world, this was a woman who wanted to efface her trace. Or so the rhetoric goes.

We’re used to hearing that women artists have been ‘rediscovered’, ‘resurrected’ or ‘reinserted’ into art history. Last year Tate was praised by The Art Newspaper for placing women artists foremost in its 2015 programme. Since then we’ve seen Sonia Delaunay upstage Robert, Agnes Martin wrenched from the asylum and Barbara Hepworth portrayed as a subtle strategist who carved her own niche. In January next year the Saatchi Gallery will stage its first exhibition dedicated to female artists. The original title ‘A Woman’s Hand’ was changed to ‘Champagne Life’, sidestepping the idea of craft in favour of celebration.

We’re used to hearing that women artists have been ‘rediscovered’, ‘resurrected’ or ‘reinserted’ into art history. Last year Tate was praised by The Art Newspaper for placing women artists foremost in its 2015 programme. Since then we’ve seen Sonia Delaunay upstage Robert, Agnes Martin wrenched from the asylum and Barbara Hepworth portrayed as a subtle strategist who carved her own niche. In January next year the Saatchi Gallery will stage its first exhibition dedicated to female artists. The original title ‘A Woman’s Hand’ was changed to ‘Champagne Life’, sidestepping the idea of craft in favour of celebration.

The Hepworth has chosen the title ‘Wild Girl’ for its exhibition of the artist Gertrude Hermes, a contemporary of Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore and a fellow practitioner of direct carving. As the first major exhibition dedicated to Hermes in 30 years, could this be a sort of ‘rewilding’? It’s unlikely, as Hermes wasn’t a radical artist and this isn’t a radical show.

The Thames Near Its Source 1933, Gertrude Hermes Courtesy the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology © The Gertrude Hermes Estate

Hermes is best known for her pantheistic prints which echo the rhythms and symmetries of nature: bodies blend, foliage blooms and foetus-like creatures are contained in pulsating spaces. Her work is the embodiment of what the artist Eileen Agar called a ‘sort of womb magic’. A similar emphasis on fluidity and transformation can be seen in the wooden sculptures, responding to the grain and original form of the block. Most prominent is The Heart of the Matter (1966–67), in which the recurrent motif of the whirlpool emerges from a flat plank of wood.

Hermes first learnt the art of carving at Brook Green School of Art under the tuition of Leon Underwood, whose students included Moore and Agar. Direct carving was regarded by critics as regressive and wood carving in particular was seen as a feminine craft, a hobby less dependent on physical strength. Hermes defied critical snobbery with sculptures made from found materials, including skittles from the local pub. Among the objects on show are the wooden trenchers she carved for her children, designed for scoops of mashed potato and slops of rice pudding.

Two in One (also known as Head and Totem Head) 1937, Gertrude Hermes Photo Alex Ramsay © The Gertrude Hermes Estate

After her divorce from the artist Blair Hughes-Stanton in 1933, Hermes’ position as a single mother was assimilated into her practice. Denied a room of her own, Jane Austen would famously hide her writing under a sheet of blotting paper when she heard footsteps approaching, but Hermes had no time for such niceties. She worked on her prints at the kitchen table and carving took place in a room upstairs. On visits to the beach at Pett Level, she would carve pebbles as her children paddled.

Also at the Hepworth is an exhibition of the work contemporary artist Enrico David – an interesting choice considering his emphasis on The show has a playful, pop-up-book aesthetic and provides a sensitive backdrop to Hermes’ work: drawings defy gravity, sculptures sink and subside. Giant dragonflies are suspended from strings while cast-iron spheres roll across the floor — David calls them dragonfly dung, or droppings from the nib of a ballpoint pen. Loping, erudite and softly spoken, you couldn’t accuse him of domination.

Writing in RA Magazine last year, Eileen Cooper RA advocated a form of positive discrimination towards women artists. The Hepworth, like many galleries, is putting this in to practice. Some might say that positive discrimination just emphasises inequality. As a modernist sculptor Hermes was hardly groundbreaking. However, as the work itself shows, she was more robust than we give her credit.

‘Wild Girl: Gertrude Hermes’ and ‘Enrico David’ are at The Hepworth Wakefield until 24 January, 2016.