From the July/August 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The Gilded Age is back, and not just for a third season of Julian Fellowes’ period drama of that name. In April, a writer in the Atlantic asked, ‘Is the US in a Second Gilded Age?’; he had perhaps not read a New Yorker article on the subject, ‘The Gilded Age Never Ended’, from February. Both pieces reacted to the inaugural address of President Trump, who proclaimed that ‘The golden age of America begins right now.’ By that he meant a return, of sorts: to the time of Presidents William McKinley, who ‘made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent – he was a natural businessman’, and his successor, Teddy Roosevelt, whose Panama Canal Trump vowed that he was ‘taking […] back’ for ‘history’s greatest civilisation’. Behind him, three of the world’s richest men – Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos – checked their phones.

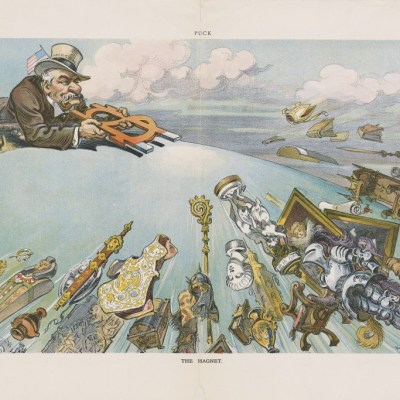

Golden – or gilded? When he first coined the term in The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873), Mark Twain was pointing to a new development in the relationship between money and power in Washington: namely, that purses directed policy. The observation that nothing was as clean – or as splendorous – as it seemed morphed from economic critique to aesthetic complaint for novelists such as Edith Wharton and Henry James, whose chronicles of the lives of New York’s monied classes are the basis for the HBO show. Missing, however, is the bite of their satire. In the 1890s, the ‘Gilded Age’ was a reproach to adulterated wealth and bad taste. Today we might be forgiven for thinking it a byword for bull markets and social climbing.

Tiffany & Co. gold opera glasses studded with pearls and rose-cut diamonds were a wedding gift for the future George V and Queen in 1893. Royal Collection Trust. Photo: © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection Trust

Painting the heroes – or, more often, heroines – of those decades was the American painter John Singer Sargent, the centenary of whose death comes at a moment full of conflict about what the Gilded Age was and anxiety about the possibility of its return. Three new exhibitions staged on both sides of the Atlantic – ‘Sargent & Paris’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (until 3 August), ‘Heiress: Sargent’s American Portraits’ at Kenwood House (until 5 October) and ‘The Edwardians: Age of Elegance’ at the King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace (until 23 November) – avoid this source of friction, and, in so doing, miss the chance to make a Sargent for our unresolved present. On the one hand, there is the popular zeal for the aesthetics of a time characterised by sham glamour. On the other, there is the fear that a gold-plated Oval Office is too neat a symbol of plutocratic rule and pedestrian taste.

Sargent was working when capitalism was reshaping the norms of life and patterns of movement for everyone, but especially for those at the top. From the comfort of a transatlantic steamer, Henry Clay Frick could crush his workers’ efforts for higher pay and shorter hours and, at the same time, snatch up the choicest pieces from a penniless aristocrat’s collection. His Fifth Avenue mansion (newly reopened with a catalogue prefaced by – who else? – Julian Fellowes) erased his origins in provincial Pennsylvania and proclaimed, in every Sèvres vase and Flemish master, the size of his wallet and perfection of his taste.

The Gilded Age redefined affluence and, with it, the look of opulence. This was the era for which the phrase ‘conspicuous consumption’ was invented and, though Thorstein Veblen was writing about the United States when he came up with it in 1899, that sentiment described the situation across the pond, too. The British luxury market was dominated by the super-rich who sailed across borders looking to purchase names that didn’t need translation, and it was in England that Sargent became as much a brand as Fabergé, Cartier, or Tiffany. In The King’s Gallery, portraits such as Louise, Duchess of Connaught (1908) compete with the guilloche-enamelled snuffboxes and diamond-wrapped cigarette cases acquired by Britain’s Playboy Prince and his fashionable family. Other painters struggled to keep up: Luke Fildes’s Queen Alexandra (1905) reduces to a run of burnished butter a netted gold coronation dress made to blaze beneath the newly installed lighting in Westminster Abbey. But Sargent, trained in Paris during the heyday of Impressionism, was better prepared for such innovations. Beaming that movement’s light on to a world of things, he could see social gradations in the glint of a flashy new bangle and the dull shine of an inherited brooch.

Madame X (1883–84), John Singer Sargent. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

For his portraits of tycoons, celebrities and other arrivistes, Sargent has been regarded as a ‘gun for hire’ – a cunning artist who painted dollars and minted money – and even called a ‘Gilded Age apologist’ who laundered the ill-begotten wealth of his clients. It is better to say that he was a speculator, betting correctly that the boom-and-bust cycles of markets and of society would need a portraitist who could secure, salvage or remake identities. You would never guess that the subject of Madame X (1883–84), the centrepiece of the Met’s show, was the child of bankrupted Confederates and the wife of a guano magnate. Her apparel alludes, instead, to the station she earned: the half-moon tiara pressed into auburn-dyed hair overpowers her subtle smudge of a wedding band and crowns her as one of the French Third Republic’s ‘professional beauties’ – a title given to those women who skyrocketed to the top of a regime oiled by money and in thrall to fame.

There is a reason we still know Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau as Madame X – and not just because Sargent insisted on keeping the title when he sold his painting to the Met. Sargent was a portraitist, but he was also a typologist, documenting what Max Beerbohm deemed a ‘nervous age’. Call it the belle époque, the Edwardian, or the Gilded Age – the variety of locution could come down to linguistic difference, or geographical specificity – but the late 19th century, in America as in Europe, had little idea what to make of itself. Designers revived styles from the Renaissance to the 18th century, seeking historical hooks for an indistinct age. Sargent, too, had his references ready.

Margaret ‘Daisy’ Hyde Leiter, later Countess of Suffolk (1898), John Singer Sargent. Kenwood House, London (English Heritage). Photo: Historic England Archive

In his portraits of the young women who left America for the British peerage (‘buccaneers’ of a new age, as Wharton called them, or ‘dollar princesses’ in a more derogatory term then-common in the press), Sargent slotted subjects into an art-historical lineage that was not theirs by birth. Kenwood’s portrait of Daisy Leiter (1898), the 19-year-old heiress to a real estate fortune in Chicago, would have hung in Charlton Park beside the well-varnished likenesses of her husband’s forebears. As is usually the case with Sargent, the ambition is in the accessories: with her chiffon shawl flapping in the imagined breeze of a generic landscape, Leiter is a Gilded Age Gainsborough ascendent, like Bernini’s Saint Teresa. Pauline Astor (1898), which depicts the great-niece of Mrs Astor (Iron Lady of New York’s established elite and antagonist of Season 2), picks up that Old Master’s feathery fall foliage in the silky brown tufts of an exquisite fur muff – a nod to its subject’s fur-trapping roots. Sargent could erase the seams between ancestral and aspirational. Reinvention was not a pretension to be derided but an enterprise to be emulated at the level of paint. Madame X’s sinuous contours and too-pale skin, for example, suggest the showy artifice of Bronzino, while her haughty chin conjures the self-possession of Canova’s Pauline Bonaparte (1805–08). Her crystalline slip of a sleeve, salaciously repainted, is a swing to surpass the notoriety of The Lady with the Glove (1869), the prize-winning Parisienne painted by Sargent’s teacher Carolus-Duran.

Though Kenwood tries to separate the story of the sitters from their costumes, sparkling personalities and glittering things are inseparable in the painter’s work. Sargent eventually swore off full-length commissioned ‘paughtraits’ – ‘especially,’ as he wrote in 1907, ‘of the Upper Classes’ – but the painter seems to have been at ease in the country homes of the Cartier cosmopolitans. Perhaps what makes us queasy about Sargent is how adeptly he rendered a style of wealth that fascinates and repels us in equal measure.

The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882), John Singer Sargent. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

When bad money creates good art, it can be disappointing. But when bad money makes bad art, it is unforgivable (though it flatters the rest of us by confirming that money can’t buy taste). The look of ‘quiet luxury’ popularised in Succession, another HBO hit about the hyperprivileged, is lorazepam for the eye: dull and cold, it sucks the saturation from the screen. Its extrovert cousin, the casino aesthetic imported from Trump Tower to the Oval Office, is much louder but equally monotonous: gold careens from floor to ceiling in an ersatz Versailles. More dubious than its grade is its originality. It is extravagantly mind-numbing. Sargent painted a time when all that glittered wasn’t gold: it was pearly white, slick brown, deepest black and an astonishing, furious red. Bravura brushwork matched surfaces stroke for stroke: the appraiser’s eye is stamped in every brash smear. Critics alleged that Sargent churned out his portraits (‘What’s the point of always repeating the same things?’, André Michel said about the portrait of Winnaretta Singer at the Salon of 1891), but these were not canvases created on the factory line. In an age of mechanisation, Sargent insisted on the artist’s hand; in an age of corporatisation, he painted individuals. Perhaps modern nostalgia for Sargent’s stubborn emphasis on tradition should come as no surprise at a time when Studio Ghibli-style memes can be made with the same AI that steals jobs and powers Teslas.

If Sargent is a painter for the end of art, he is, in Joshua Oppenheimer’s film The End (2024), an artist for the end of days. In this post-apocalyptic musical, lining the plum-coloured and walnut-trimmed walls of a sumptuous bunker are paintings pulled from those museums – such as the Tate or the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston – that owe their collections to late 19th-century tycoons of sugar, mining, rubber and, as is the case for this 21st-century compound-owner, oil. There are Bierstadts and Renoirs and, of course, Sargents. If the light weren’t so dim, you could almost forget that these rooms are in the sunless labyrinth of a salt mine. On New Year’s Eve, the patrician family lounges in fancy dress and glugs champagne from crystal glasses. Four bored girls from the well-appointed past, in the form of Sargent’s The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882), stare out at them – and at us. They listen warily as the celebratory dinner devolves into doubts: about regret, responsibility, and the costs – and worth – of living. There’s no gold in this flat of survivors; we sense there is already guilt enough.

From the July/August 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.