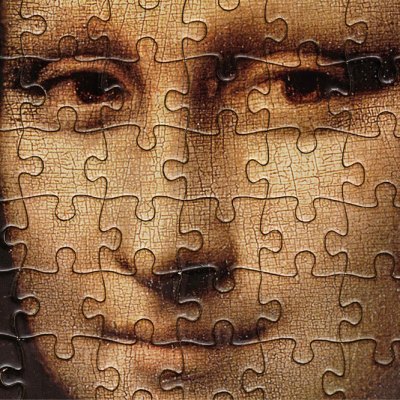

In 2014 Gillian Wearing made a photographic work titled Me as an Artist in 1984. As so often, she appears in it herself, in a bespoke and somewhat unnerving mask: on this occasion, as the title suggests, replicating her own smooth features in early adulthood, her more experienced eyes looking out, her hair teased up in a period style. Beside her, meanwhile, is a painting, an anachronistic study in biomorphic Surrealism featuring a pair of distended figures, one with huge red lips, floating in space. Until recently this was the only clue – or, if you like, confession – in Wearing’s oeuvre that, prior to her celebrated photographic and video-based explorations of selfhood and its multiplicities and ambiguities, she had once been a painter. In 2020, though, she fully unmasked herself. Her exhibition ‘Lockdown’, at Maureen Paley in London, revealed what she’d been up to in the early months of the pandemic: a suite of self-portraits in deft oil and limpid watercolour.

Me as an Artist in 1984 (2014), Gillian Wearing. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London/Hove / Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles / Regen Projects, Los Angeles; © Gillian Wearing

Nevertheless, for Wearing to do this was never going to be a simple ‘and this is me’ statement; or rather, the paintings complicate what ‘me’ is. For one thing, these studies of herself are visibly refracted through a prism of artistic inspirations. Untitled (lockdown portrait) (2020), a three-quarter-length oil study of Wearing looking broodingly downward in a sombre burgundy dress, aligns itself with the aesthetics and moods of Gwen John, feeling rooted in the present moment and a century earlier. Other works are replete with echoes of painters who, Wearing says, inspired her in her first, relatively traditionalist stint at art school, at Chelsea School of Art – figures such as Lucian Freud, Leon Kossoff and John Singer Sargent. But these paintings could, arguably, only have been made by an artist who then went on to the conceptual rigours of an education at Goldsmiths. As much as we see Wearing in them, they’re also modulated by what we’ve come to know her for. That is, seeing selfhood as composite and self-knowledge as a process; and making lens-based works such as, in recent years, variously self-invented and meticulously recreated portraits of artists who’ve influenced her – including Robert Mapplethorpe, Marcel Duchamp and Eva Hesse – starring herself sporting prosthetics. Her painting show opened with a sculpture, a face mask wearing a surgical mask. One might ask: is self-portraiture here a mask over a mask?

Mask Masked (2020), Gillian Wearing. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London; © Gillian Wearing

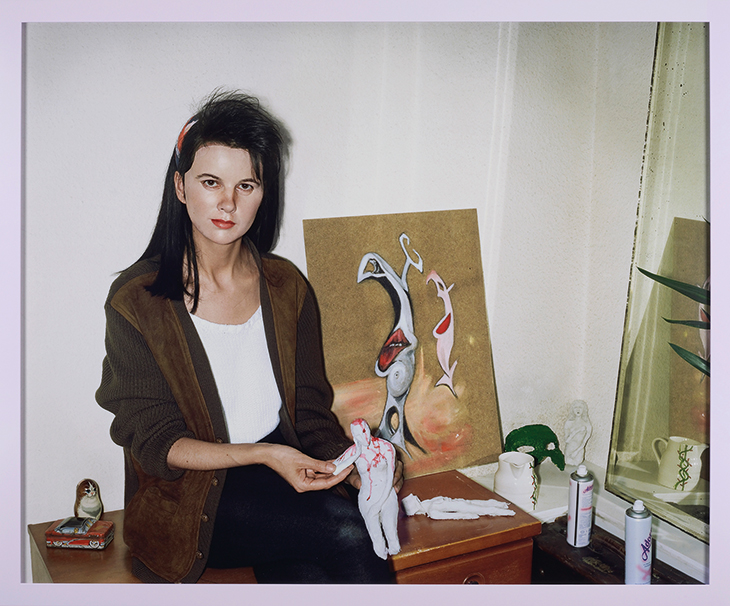

What we might safely say is that Wearing, whose artistic approach seems encoded in her very surname, is signalling from inside. Since early in her career, she’s been interested in how masquerading paradoxically allows the wearer to be honest, or to access something deep about themselves: see, for example, Confess All on Video. Don’t Worry You Will Be in Disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian… (1994), in which volunteers spill intimate secrets while concealed; or the photographic sequence Album (2003), in which she inhabits the roles of her mother and father in their youth and, causing double takes, her brother as a tattooed, shirtless longhair. In the photo-triptych Rock ‘n’ Roll 70 (2015) she presented herself at her then-present age and, via time-accelerating make-up and greyed hair, as a septuagenarian in the same pose, the last panel left blank for the real documentation when the time comes. The Lockdown paintings, too, are evidently the products of an inward journey. As much as we glimpse the distant progenitors in them, we also see an artist as bruised as all of us by the horrors of the last year. By turns, Wearing looks tired, resolute, pinched, cycling through a spectrum of moods and thrown back on herself in a way that feels painfully familiar.

Rock ‘n’ Roll 70 (2015), Gillian Wearing. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London/Hove / Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles / Regen Projects, Los Angeles; © Gillian Wearing

Contacted via email, Wearing says she had actually been re-engaging with painting since 2006, and that lockdown gave her leeway to pursue it. Several factors appear to have dovetailed: the desire, continuing her interest in transporting herself into different time periods of her own and others’ lives, to revisit a former medium; the opportunity to do so in relative quiet; and the heightened emotional context. ‘I couldn’t and to an extent still can’t get my head around these times and what they actually mean,’ she says. ‘I think my paintings recognised and related to that sense of ennui, helplessness, and uncertainty lockdown has brought with it… for me in this recent body of work I felt I was approaching things with sincerity. It helped that I was once removed, more than in a photograph, as I had to create an image from a blank canvas. So you really are studying yourself without a filter.’

Untitled (lockdown portrait) (2020), Gillian Wearing. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London; © Gillian Wearing

Wearing’s work, fittingly for an artist who zips around in her own chronology, has a dynamic relationship to time in terms of reception. Either it’s right for the moment, as in the lockdown work, or it works in the present and becomes something that, later on, feels right in a new way, prescient. Alongside the paintings, she chose to show last year at Maureen Paley the evolving video Your Views (2013–ongoing), which was designed as a remote, online project in which people submit filmed views from their windows: a kind of reverse voyeurism and also, it turns out, a slow-motion documentary of the UK in recent times. ‘Our views,’ Wearing notes, ‘have become something that in the past year were our only connection to the outside world. The film has become a document of the changes, as it has captured the quiet streets during the first lockdowns, the clapping for essential workers. Then we have the views taken before the pandemic, and soon – hopefully – the ones that will be after.’

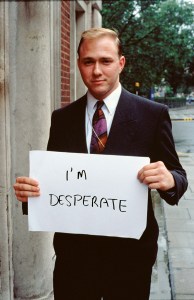

Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say I’M DESPERATE (1992–93), Gillian Wearing. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London/Hove / Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles / Regen Projects, Los Angeles; © Gillian Wearing

Statue of Millicent Garrett Fawcett (2018) by Gillian Wearing in Parliament Square, London. Commissioned by the Mayor of London with 14–18 NOW, Firstsite and Iniva through the Government’s national centenary fund. Photo: GLA/Caroline Teo

As she affirms, this work’s collaborative mien and emphasis on the individual viewpoint puts it in conversation with her breakout work, the much-mimicked Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say (1992–93). From our contemporary vantage, Wearing’s street-sourced volunteers communicating in constrained, sign-sized space – the sleekly suited city type holding a sign that reads ‘I’m desperate’, the tattooed man whose message is ‘I have been certified as mildly insane!’, the baseball-capped Black man asserting that ‘The political situation in England is stable’ – seem uncannily predictive of social-media users, even as they enact a difference between appearance and opinion. The signs are essentially analogue tweets, avant la lettre. Before you could see it on the internet, here was evidence of the continual, concealed, Joycean swirl of thought and feeling in the minds of everyone you passed on the street. (This civic quality, attention to how inwardness operates in and against public space, also has a bearing on Wearing’s ventures into public sculpture, such as A Real Birmingham Family [2014] and her bronze effigy of the suffragist Millicent Fawcett, the first statue of a woman in Parliament Square [2018]).

‘I feel grateful that many of my works have stood the test of time, but more importantly predated some of our concerns and ways of expressing ourselves now,’ says Wearing. ‘The Signs series foresaw the age of social media and the possibility of having a platform so that everyone can perhaps have a voice, and give expression to their inner thoughts – positive and negative though that may be.’ Her work with masks feels prescient, too, given both how social media allows people to speak anonymously and how various phone apps allow users to customise their appearance. (Perhaps needless to say, it also anticipated the burgeoning and ominous development of deepfake technology, machine-learning-driven replacements of one person’s features with another in video; which points up another aspect of her achievement, that she refuses to use digital trickery.) And an early piece like Dancing in Peckham (1994), featuring Wearing unashamedly dancing alone in a south London shopping centre, not only scans differently in an era when filming oneself is standard, but also seems anticipatory of the dancing crazes on TikTok and the like, and the general self-exposure underwritten by YouTube.

The standard text to refer to in relation to Wearing’s work is Erving Goffmann’s book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956), in which the sociologist depicts human interaction as essentially theatrical, all of us wearing disguises, all performing socialised roles. Wearing’s humanistic insight is that this can also be a form of freedom: it allows for unburdening – in online forums, for example – and also, if you change the mask, for escaping the prison of selfhood, of fixed identity. Wearing’s art has performed some limited conditions of this: what does it feel like to become your mother, your father, your brother, your artistic heroes, yourself as a younger and older version of you? ‘So much of my art,’ she says, ‘is rooted in the “performative” aspect of making it. An element of process and performance permeates much of what concerns me.’ There are aspects of Wearing’s work – how it has changed her to go through what she’s gone through to make the work – that will never be accessible to an audience. But the act of imagining ourselves inside the minds and bodies of others is available to us at any time. That’s an element of the humility that permeates Wearing’s self-portrait paintings – which feel like the opposite of an artist putting themselves on a pedestal, more a creative figure revealing herself to be as broken as the rest of us. It’s known as empathy.

Gillian Wearing’s Lockdown Portrait 5 on the left and Untitled (lockdown portrait) on the right (both 2020). Courtesy Maureen Paley, London; © Gillian Wearing

That quality and that ability to project, as we physically disconnect from each other more and more – both voluntarily via our devices and, lately, involuntarily – are increasingly vital. Art galleries themselves, where we mill around among unknowable strangers, are places to practise it. In recent months, when not painting, Wearing has been preparing with fingers crossed for a ‘survey crossed with a retrospective’ at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. An exhibition that will no doubt highlight the predictive nature of her practice over the past three decades, and that will, says Wearing, bring together key works with a curatorial sensitivity to how they influenced each other, it will also likely offer a double spectacle, given the primacy of the public in her work. There’ll be a swathe of Wearing’s art: a parade of figures, most of them the artist herself, behind some kind of disguise, or people we don’t know offering evidence of their teeming interiorities, happy to have been given a voice. And, perhaps seeming newly present in the light of the artist’s democratic achievement, there will be the audience. That is, other people we don’t know, with rich and mysterious interior lives and opinions, who might tell their secrets if they thought they could get away with it. Composites of influence and familial genes, and also individual. All wearing masks in order to live.

From the March 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.