The death of Giorgio Armani at the age of 91 has been marked by an outpouring of obituaries and tributes. Designers often become household names – putting one’s name on a perfume bottle or a pair of sunglasses will do that for a person – but rarely, in the popular imagination, because of the clothes they have created. Few designers change how both men and women dress and also define a decade. And, by several other yardsticks of success, his achievement was remarkable.

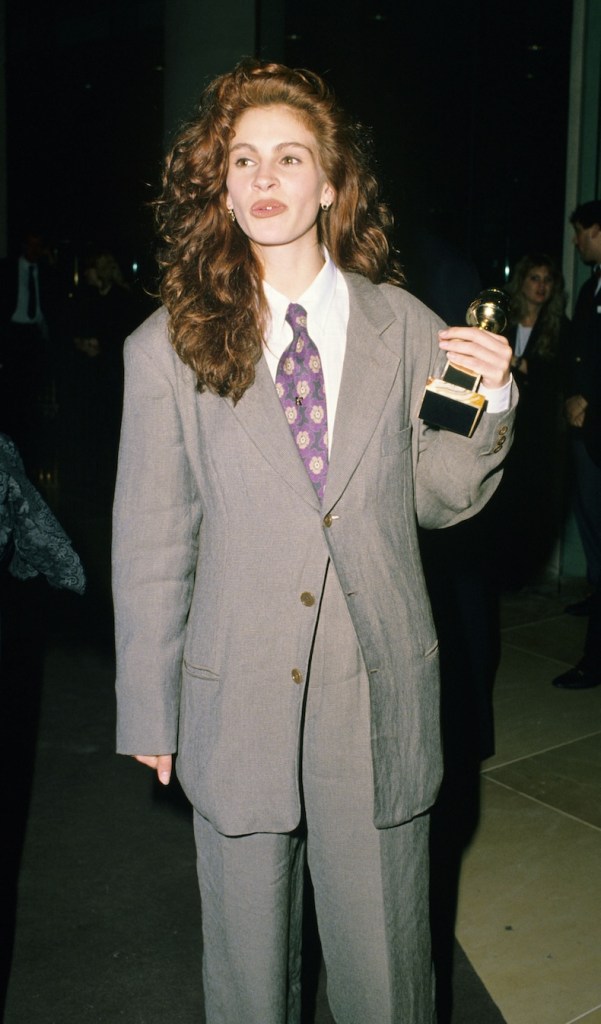

If, at the dawn of the 1980s, Armani relaxed the line of men’s suits – as Richard Gere showed to pantherine perfection in American Gigolo – he also stiffened the silhouette for women and threw in some shoulder pads for good measure. Other films outfitted in Armani included The Untouchables and Goodfellas; film stars who wore it in real life, or on the red carpet – since he was among the first to see the value of giving them clothes – included a roll call of women who didn’t want their clothes to wear them. Julia Roberts accepting a Golden Globe in a men’s Armani suit (1990) will forever be more soignée than Julia Roberts accepting an Oscar in a princessy vintage Valentino dress (2001).

Giorgio Armani certainly loved film. In Made in Milan (1990), a short documentary made by Martin Scorsese, he said that he would have liked to have been a director. No matter that the remarkable level of control he exercised over his empire suggests he already was. But his artistic endeavours could also be seen on stage. In 1995, Jonathan Miller called on Armani to design the costumes for a modern-dress production of Cosi fan Tutte at the Royal Opera House in London. The director’s idea, he said, was to ‘do a really updated version of it and set it in last Thursday afternoon’. The decision to get Armani on board ‘was a way of getting cheap costumes that we didn’t have to pay for’. (Miller, not someone who enjoyed his considerable talents being underestimated, seemed a little irked that subsequent revivals were always called ‘the Armani production’, even when the costumes were no longer designed by Armani.)

And, in an era when fashion exhibitions were becoming a big draw for museums, the Armani retrospective that opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2000 was a behemoth. Designed by the late Robert Wilson, another figure who moved between worlds with ease, the exhibition was on the road for another five years, touring the Guggenheim Bilbao, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the Royal Academy of Arts in London and other venues. It was also controversial, with the New York Times reporting that Armani was making a significant donation to the Guggenheim in New York, perhaps as much as $15m. The news wouldn’t raise much of an eyebrow now and in this, as in so many other endeavours, Giorgio Armani was well ahead of his peers.