From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Before the opening of the Olympic Games in Paris this summer there were some mild expressions of disappointment that the restoration of the cathedral of Notre-Dame, gutted by fire in 2019, wasn’t quite complete. It is, however, due to reopen in December so President Macron’s promise to have the building restored in five years looks likely to be met: the scaffolding is down and a vital part of global heritage is almost ready for the public again. It’s a testament to the cultural importance of this 13th-century heap of stones (and the largesse of Bernard Arnault, luxury goods tycoon and contender for world’s richest person) that there was essentially no question of its immediate and painstaking restoration.

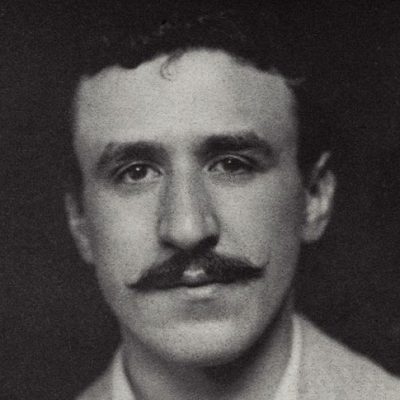

Meanwhile in Glasgow, at the other side of the Auld Alliance, Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s School of Art, possibly the greatest work of architecture of its generation in the world, is a broken shell hidden behind scaffolding, its future increasingly uncertain. Struck by two separate fires, the second a complete gutting out, the building has been at the centre of a story of mysteriously unsolvable conflagrations, over-ambitious management, botched procurement, heel-dragging institutions and the madnesses of the modern university, and it’s not clear that the end result is going to please anybody.

Things could always, however, be worse. The first of the two fires occurred during preparations for the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) degree show in 2014, apparently due to expanding foam being ignited by an old film projector, with the flames making their way up a dormant old ventilation system. The library, the most significant of the interiors, was destroyed, but the majority of the building remained intact. The aftermath of this blaze allowed for a comprehensive survey to be undertaken, which involved digitally scanning the whole building and also investigating beneath its surfaces, learning important lessons about how Mackintosh and the builders had gone about putting it together in the first place. The fact of this first fire means that, for restorers of the shell that exists now, there is the best possible documentary material from which to mount a restoration.

The entrance of the Glasgow School of Art building before the devastating fires of 2014 and 2018. Photo: Chris McNulty/Alamy Stock Photo

But what form will this restoration take? In the weeks after the 2018 fire, it wasn’t at all clear what, if anything, would be salvageable, and there was an assumption that much would need to pulled down. Unlike contemporary buildings, which are almost all heavy internal structures clad in more lightweight materials clipped to the outside, Mackintosh’s building was a heavy masonry structure mostly spanned by timber floors and roofs. Photos of the fire damage show thick charred walls of brick and sandstone that carried all the vertical loads, but the big timber floor joists were all broken and piled up at the bottom of multi-storey chasms. These not only carried the weight of people and furniture to the walls, but also held the walls in place and, when all the timber burned away, what was left was intrinsically unstable and liable to collapse.

In the event, the walls were quickly stabilised and found to be largely intact and, with the debris cleared out, the current condition is very similar to what happens when the facade of an older building is retained while everything else behind it is rebuilt, a common heritage strategy disparagingly referred to as ‘facadism’. Mackintosh’s building has been transformed into a symbiotic pairing of the masonry remains and a utilitarian steel structure holding everything in place, all currently sheathed in a slick plastic covering that is allowing the remains to dry out.

One oft-criticised aspect of ‘facadism’ is that it reduces the historic value of a building to simply the half-metre or so depth of its exterior, with everything behind considered worthless. The Mackintosh building, one would imagine, would be able to avoid that fate, but after each of the fires there was quite a lot of talk of holding competitions for new designs, ostensibly in the hope of finding another young genius like Mackintosh himself – though it was easy to form the impression that certain architectural grandees were fishing for the plum job themselves. The public mood was fairly consistent that the building should be restored ‘as was’, and in 2021 the GSA confirmed that a ‘faithful restoration’ was indeed its aim.

‘Faithful restoration’ in this case means a recreation of all of the significant spaces of the building – the library, the lecture theatre, director’s office and so on, as well as the studios, while making sure that the building conforms to contemporary regulations. In practice, while this locks in place the shape of the rooms and the materials used, behind the skin there is scope for things to change – the use of steel or concrete within floors for strength and fire resistance, for example, or the removal of the obsolete ventilation ducts that got the building into the mess it’s in now.

Doorplate at the main entrance of the Glasgow School of Art, bearing a font designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Photo: Kenny Williamson/Alamy Stock Photo

Something that ought to make the refurbishment easier is that much of the building’s interior was decorated very simply. Elsewhere, walls were covered in a polished cement plaster nicknamed (and not entirely negatively) ‘Glasgow Marble’, and even the famed library was basically veneers attached to cheap timber brought up from the shipyards. Unlike at Notre-Dame, there will be little need for master craftsmen to replace fine sculpture or stained glass. On the other hand, Mackintosh created a large amount of highly expressive ironwork, including symbolic representations of the Glasgow coat of arms, and insect motifs inspired by Japanese art seen at International Exhibitions, and much of the finer character of the building comes from those. Thankfully, this is industrial craft, and these objects have been documented very thoroughly.

Despite these silver linings, things started to go awry quite early on in the process. The Scottish Parliament held a preliminary inquiry into the fire, during which a number of witnesses criticised the board’s expertise and their priorities, suggesting that the building should be placed in a trust. A tit-for-tat unfolded between the school and the Scottish government, with the latter accusing the former of ‘seek[ing] to question the credibility of the evidence provided by some of the witnesses’. In the fallout, the director of the GSA, Tom Inns, resigned in November 2018 after a rift with Muriel Gray, the school’s chair. In 2020, a tutor in the architecture department and expert witness, Gordon Gibb, was sacked for publicly criticising the Art School’s board at the inquiry.

Another ominous sign was the fact that the investigation into the 2018 fire, which reported back in 2022, concluded that its cause could not be determined. This may well be the case, but Glasgow has a terrible reputation for unexplained fires, with the usual weary understanding being that these are set by developers or owners to get rid of troublesome buildings. While it is impossible to believe that the GSA would act like gangsters to rid themselves of this troublesome building – dark jokes about Muriel Gray being a pyromaniac notwithstanding – this unwelcome echo was an ill omen.

More blunders followed. The initial procurement process set up by the GSA had to be abandoned after a series of bungles meant that it tried to award first place to two different architects, leaving itself millions out of pocket and no closer to getting any work done. Since then, the school has been stuck in arbitration with its insurers, and while it has started a new procurement process, the commencement of any work seems a long way off.

The library, seen here in 2006, is the heart of the art school and at the centre of appeals for a complete post-fire restoration. Photo: Maurice ROUGEMONT/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

At this stage in the process, there are even more troubling questions. The 2018 fire destroyed a number of buildings on the same city block as the Mackintosh building, and they still remain undeveloped. Sauchiehall Street, the main road just to the south of the building, is in as sorry a state as it has been since the 1980s, with many large retail units empty and abandoned. Glasgow, while thriving in some ways, is clearly struggling financially, and this makes the outlay on the rebuild harder to justify. Some of the only new buildings being built in the city are large blocks of student housing for the international market, and indeed an extremely large one of these is currently proposed to take up much of the remains of the Art School block, threatening the setting of the building before it even has a chance to return.

One of the unique selling points of the Glasgow School of Art was the way in which the Mackintosh building was still being used for the same purpose for which it had originally been designed. Guided tours passed around throughout the day, tourists in bumbags taking photos of paint-spattered students, the smell of white spirit everywhere. It’s a glorious asset to have, spiritually, but on a spreadsheet it probably makes for quite a different story – a high-maintenance building with severe restrictions on how it can be altered, and in today’s market of global competition for higher education students, how much of a draw is such a building anyway? Given the financial crisis in UK universities, it would not be at all surprising if the GSA is less enthusiastic about ‘the Mack’ than it was, and is hoping that its transformation into a museum will become inevitable.

Everywhere you look there are warnings. David Chipperfield, celebrated architect of the Neues Museum refurbishment in Berlin, has commented in support of the ‘faithful restoration’ strategy but has warned of the ‘enormous amount of money’ that it would require to do correctly. Respected Scottish architect Paul Stallan has been lobbying to scrap Scottish procurement rules that automatically favour cheapest options, which on a delicate project like this are a recipe for shoddiness. Alan Dunlop, an architect who at times has argued for a new building entirely, worries that ‘the whole faithful reinstatement is at risk and we’ll never see the Mackintosh building again’. More recently, Paul Sweeney, a Labour member of the Scottish parliament who is one of the most vocal public figures fighting for the preservation of Glasgow’s heritage, has called the project an ‘unmitigated disaster’ and demanded that it be taken over by the government to guarantee its completion.

A project like this, of local and global significance, needs to be executed properly and it’s not clear that this is really being grasped. At this stage it is not completely guaranteed that the project will restart at all, and there is a strong and unhappy chance that the plan that is taking shape will be inadequate to the priceless cultural heritage that the Mackintosh building represents.

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.