For his current exhibition at Gallery 1957 in Accra, the British-Ghanaian artist Godfried Donkor has expanded on themes that have long absorbed him – the lionised figure of the boxer, and boxing’s historical entanglement with the slave trade.

How did you become so fascinated by the figure of the boxer?

When I was young, I was fascinated by stories of heroes. I used to read Greek myths and Scandinavian stories, then I got into comics – so I’ve always been into superheroes. For me, the boxer represents the closest I can get to a superhero-type figure, someone larger than life. If you read the stories of Daniel Mendoza, Tom Molineaux, Bill Richmond, Muhammad Ali, Jack Johnson, they often seem larger than life.

Jack Johnson, for example, was this amazing character – he was one of the first people to have a car in America – and he was hated for being black, but he lived such a full life despite that. He was once asked to describe how hard it was for him to be a black man in America, in 1905 or 1910, and he said, ‘Well boys, I was just a brunette in a blonde town’. That’s how he described being black in America at the turn of the century, he just kind of strikes it off. I find that visually so compelling: it makes me wonder, ‘How do I paint that? How do I paint somebody who says that the racism, the untold racism that he experienced was just because he was a brunette in a blonde town?’

The exhibition at Gallery 1957 has the title ‘Battle Royale: Last Man Standing’. Why have you chosen to invoke the idea of a battle royale, or a free-for-all fight – which was sometimes staged between bare-knuckle boxers in the 18th century in the United Kingdom, and until the 20th century in the American south – as an overarching concept for the show?

The battle royale has been a fascinating visual reference for me – you don’t often see images of it, but there are texts about it. There are descriptions of crowds of white men in southern America watching a group of black men beat themselves up, and then throwing coins on the floor for the last man standing. And then you read about aristocrats in clubs in London, in the 18th century, also staging these performances where local men would be given an incentive to come to these posh clubs and bash each other up for the pleasure of the aristos, who would be betting on them. A lot of the images that I try to produce come from reading about something and thinking, ‘What would that look like? How can I put it into modern-day contexts?’ I wait for enough material to gather in my mind, visual material that I can put together.

This show is ‘Battle Royale: Last Man Standing – Part 1’. The idea is that the second part will probably encompass a more local scene, the Ghanaian boxing scene. There are examples in Ghana, and elsewhere in Africa, of a group of young men being put into an arena and asked to fight it out. That’s not a battle royale, because it doesn’t have the privileged audience – the spectators are from the community.

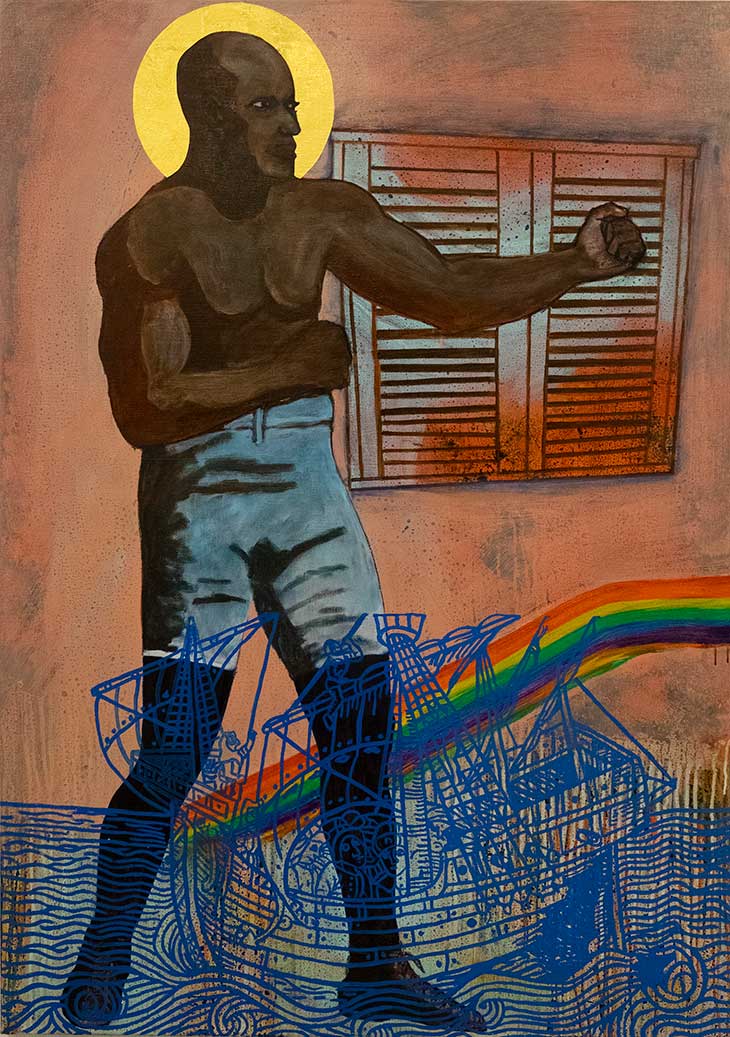

ST JACK JOHNSON, ‘a brunette in a blond town’ (2019), Godfried Donkor. Courtesy Gallery 1957

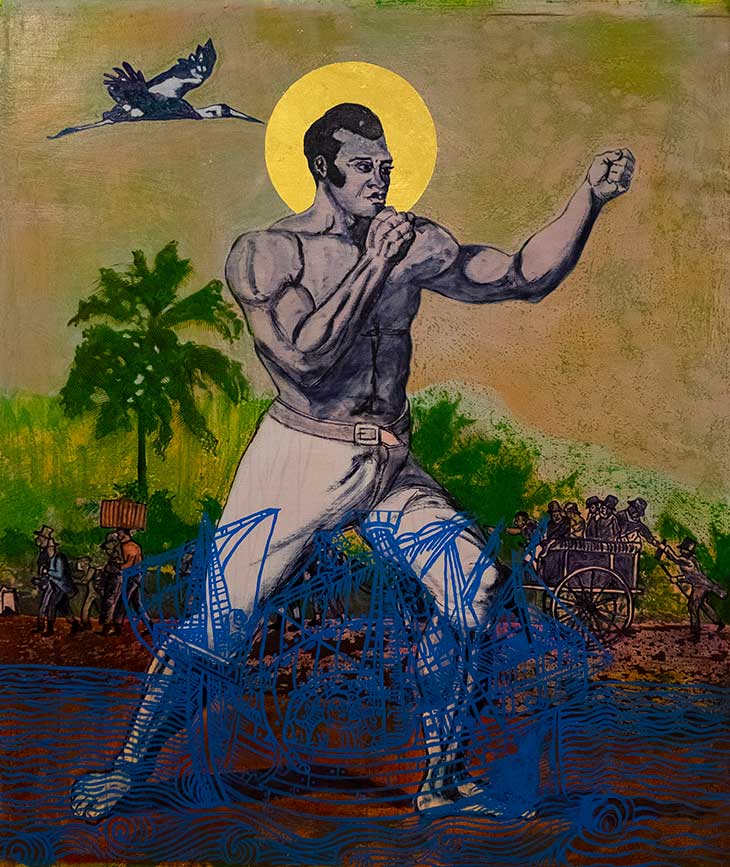

In the paintings of historical fighters in this exhibition, the boxers have been sainted – St Bill Richmond, St Thomas Molineux – and their heads adorned with golden haloes. How might that influence how we look at them?

Saints martyred themselves for their faith: that’s the Catholic ideal. But I found that these guys were also historical martyr figures, in a way. George Stevenson died after a fight [in 1741], which brought about the first regulation of bare-knuckle fighting – although they still fought 50 rounds. I like to combine historical fact with mythology in my work.

ST JACK BROUGHTON vs ST GEORGE STEVENSON (2019), Godfried Donkor. Courtesy Gallery 1957

And those haloes also evoke medieval gold-ground paintings…

Yes. My earliest reference point at art school was looking at the classical artists and the history of art – and I’ve always been fascinated by the use of gold in paintings, right through to Gustav Klimt. I’ve been to Russia, I’ve seen Russian icons, Byzantine icons, paintings throughout Italy, and have always thought about how I could use historical art forms to make contemporary paintings. I guess what I was looking for, in my work, was to build a stylistic language, a way of working where I could feel comfortable telling a historical story in a contemporary context.

A number of these works have the same ship painted in the foreground. Where does that image come from?

I’ve used slave ships in the past, but this ship is actually the Santa María, which was Columbus’s ship. It goes back to works that I started making in my art school days, the From Slave to Champ series, based on the idea that the history of popular boxing, especially in America, comes in relation to the slave trade. From early on, especially in the southern states, the plantation owners realised that they had very big guys on their plantations that they could earn money from by making them fight. To make a contemporary image of that situation, one of the ingredients I needed was a ship, for this idea of a journey, of transporting people.

ST THOMAS, up to scratch (2019), Godfried Donkor. Courtesy Gallery 1957

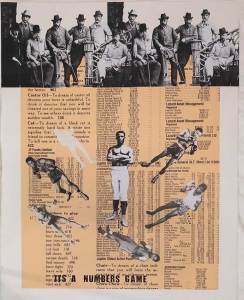

How do you select the historical images – prints, paintings or photographs – that form the basis of your boxing paintings?

Even when I was young, I would go through history books and historical archives to look for printed matter, for prints and typography that I could use to make collages or to make drawings of. The history section of a library always gave me information that I couldn’t find elsewhere.

BATTLE ROYALE, last man standing (2019), Godfried Donkor. Courtesy Gallery 1957

I’m not interested in images where the boxers are actually throwing punches, because I want them to be seen in their heroic poses. So they’re slightly taken out of the boxing arena, even with the images of a boxer in a ring, with hands up waiting to go. These are the type of images that you’ll see in bars in America or pubs in England, showing the stance of the champion of the time. Historically that type of image was posed in an artist’s studio, with the background put in after.

With these paintings, I used a lot of images that I’ve used before. I like the idea of repeated images, of evoking Pop imagery – I grew up in an era where we’d go to clubs and parties and the songs we liked were always repeated. As a kid drawing from comic books, I’d repeatedly draw Spiderman, I’d repeatedly draw Iron Man. You’re constantly repeating images of your heroes.

ST BILL RICHMOND, the black terror (2019), Godfried Donkor. Courtesy Gallery 1957

Is sport a passion of yours, as well as a subject of artistic enquiry? Could it be taken more seriously by artists?

I am a sports fan, but I’m also fascinated by the idea of sport. Every World Cup, since 1990, I’ve made images of footballers. I lived in Spain for two years, in Barcelona, and I became fascinated by how you see these postcards of footballers everywhere – they almost look like icons, so I started making paintings of footballers, again as saints. I don’t know a lot of artists who make sports pictures. But I’m interested in the fact that artists are not looking at sport – it gives me a whole arena to myself that I can delve into!

What does it mean to you to show these works in Accra?

Having spent eight months working here, I’ve noticed how different my palette has become as I’ve tried to evoke the colours that are around me. The light here is much sharper than in the UK, with three types of light – morning, afternoon and evening light. That creates a completely different visual effect.

I left Ghana as a boy, but in the last two years, since I’ve been working in Ghana – this is my second residency – I’ve become really fascinated by the art scene here, and it’s become very important for me to be able to make work here, and to show it here first.

‘Godfried Donkor, Battle Royale: The Last Man Standing – Part I’ is at Gallery 1957, Accra, until 5 October.